Abstract

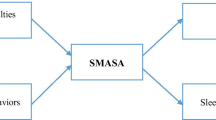

The COVID-19 pandemic has unleashed unprecedented challenges with profound repercussions on adolescents’ mental health and sleep quality. However, only a few studies have focused on the aspects potentially related to adolescents’ well-being during the pandemic. The present study aimed to understand the role of loneliness and positivity on adolescents’ mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues in the emergency period. A sample of N = 564 Italian adolescents (Mage = 15.86, SD = 1.41) participated in the survey. Hierarchical linear regression analyses revealed that loneliness was positively associated with mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues. In contrast, positivity was negatively related to mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues. Results also showed that gender moderated the relation between positivity and sleep latency. In detail, higher levels of positivity were associated with reduced sleep latency for females but not for males. Overall, our findings highlight the importance of studying the determinants of adolescents’ well-being during such challenging events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly affected individuals’ mental health worldwide and across different age groups, with detrimental effects, especially on children and adolescents (e.g., Samji et al., 2022). Adolescence is a critical development period characterized by rapid physical, emotional, and social changes (e.g., Laursen & Hartl, 2013). In the transition between childhood and adolescence, individuals gradually shift from dependency on parents and play-based interactions with peers to a greater reliance on friends and social relationships outside the family context, which are characterized by increasingly higher closeness and intimacy (e.g., Bukowski et al., 2011). Thus, the disruptions caused by the pandemic, such as social isolation, remote schooling, and uncertainty about the future, required adolescents to face unique challenges, with adverse cascading effects on their psychological well-being, including heightened levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress compared to pre-pandemic estimates (Santomauro et al., 2021). Furthermore, school closures and remote schooling have interfered with the usual routines of children, adolescents, and their families, resulting in altered sleep patterns, including increased sleep duration, delayed bedtimes, and compromised sleep efficiency (Richter et al., 2023).

Given the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as those noted above, previous research has aimed at uncovering factors by which mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues developed. On the one hand, some studies observed that negative feelings, such as loneliness (i.e., the sensation to have poor social connections; e.g., Perlman & Peplau, 1982), could represent a risk factor for young individuals’ mental health (Farrell et al., 2023; Loades et al., 2020). On the other hand, positive dispositions, such as positivity (i.e., positive orientation towards oneself, own life, and future; Caprara et al., 2012), could play a protective role against mental health problems, as reported in previous studies with adults (Qamar & Yaqoob, 2023; Zuffianò et al., 2023). However, despite the relevance of investigating the determinants of adolescents’ mental health and sleep quality during such an extremely challenging event, research in the area is still scarce. Innovatively, the current study considers the role of loneliness and positivity in explaining adolescents’ mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues during the pandemic. We aimed to identify the potential risk and protective factors affecting adolescents’ well-being, considering the context of scarce resources available due to the constraints imposed by the pandemic.

The role of loneliness

Loneliness is a negative feeling resulting from a discrepancy between the existing relationships, in terms of quantity and quality, and desirable relationship standards (Perlman & Peplau, 1982). According to Baumeister and Leary (1995), the “need to belong”, which refers to the basic necessity to form and maintain interpersonal relationships, is an essential human motivation. Establishing social connections generally leads to optimal psychological functioning and well-being, evoking positive emotions. Conversely, actual, perceived, or potential threats to social bonds give rise to unpleasant emotional states (Deci & Ryan, 2000). During the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns and restrictions on social gatherings were implemented as essential means to mitigate the spread of the virus. Therefore, face-to-face interactions with peers and friends were minimal, increasing loneliness and social isolation among adolescents (Branje & Morris, 2021; Farrell et al., 2023), potentially neglecting adolescents’ need to connect socially with significant peers.

Loneliness emerged as an important concern during the pandemic, as several studies observed that higher levels of loneliness were more likely to be related to heightened depression and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents (Zuccolo et al., 2023). As highlighted by Farrell et al. (2023), in the majority of cross-sectional studies conducted in the last few years, loneliness has been the most common indicator of children’s and adolescents’ well-being, revealing positive associations with depression and anxiety symptoms both before and during the pandemic. A negative impact of loneliness on adolescents’ well-being also emerged from longitudinal research. However, such associations were more complex, with some studies revealing interaction effects with other factors, such as the levels of well-being during the pre-pandemic and the timing of data collection (e.g., month/year). Most longitudinal studies, including a pre-pandemic assessment, indicated loneliness as a predictor of diminished well-being (e.g., Magson et al., 2021). In some other studies, after accounting for well-being indicators from the initial three months of the pandemic, loneliness did not significantly predict the subsequent aspects of well-being one month later (e.g., Cooper et al., 2021). As argued by Farrell et al. (2023), it is possible that the duration of the interval between the time points of the assessment accounted for a significant portion of the contradictory results among the longitudinal studies investigating the relation between loneliness and adolescents’ well-being during the pandemic. Some studies also found that experiencing a higher level of social connection helped protect mental health against the negative consequences of lockdown (e.g., Magson et al., 2021). While existing studies have shed light on the link between loneliness and mental health, there is still a gap in understanding how specific factors, such as homeschooling (e.g., Albrecht et al., 2022), may influence this association.

Also, the relation between loneliness and sleep quality has garnered particular interest from researchers and mental health professionals (Santini & Koyanagi, 2021). For instance, in Eccles et al.’s (2020) study, conducted before the pandemic with adolescents between 11 and 15 years of age, higher levels of self-reported loneliness resulted in poor sleep quality, altered sleep patterns, weariness in the morning, and a higher frequency of daytime drowsiness. Despite the evidence of adolescent sleep disruptions after the pandemic outbreak (e.g., Richter et al., 2023; Rocha & Fuligni, 2023), only a few studies have explored the link between loneliness and sleep quality among young people with a specific focus on this challenging period (see Farrell et al., 2023). Indeed, the predominant focus of previous research has been on exploring this association within adults (e.g., Pilcher et al., 2022; Santini & Koyanagi, 2021). Notably, some evidence suggested that an increased occurrence of sleep disruptions (i.e., difficulty in falling asleep and staying asleep during the night) emerged among children and adolescents who exhibited heightened feelings of loneliness (Dondi et al., 2021). In another study (Becker et al., 2021), the heightened self-reports of sadness/loneliness among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic were linked to an escalation in parental observations of challenges faced by adolescents in initiating and sustaining sleep. Considering the limited research conducted so far, further investigation is needed to address the potential role of loneliness on sleep quality among adolescents during the pandemic.

The role of positivity

Positivity is an individuals’ disposition to approach themselves, their life, and their future in a positive manner (Caprara et al., 2012; Zuffianò et al., 2019). It has been conceptualized as a unique factor encompassing self-esteem (Rosenberg, 1965), life satisfaction (Diener et al., 1985), and dispositional optimism (Scheier & Carver, 1993). Similarly to Beck’s (1967) theoretical model of depression, which centers around a negative cognitive triad indicating a lack of hope for oneself, the world, and the future, the construct of positivity has been theorized as a relatively stable internal predisposition that allows individuals to interpret emotionally challenging experiences through cognitive self-reflection and more adaptive thinking (Caprara et al., 2012; Zuffianò et al., 2023). From this perspective, positivity can influence individuals’ quality of life and well-being, promoting better mental health and sleep quality, especially during challenging times such as a global pandemic (Caprara et al., 2019). However, although literature on the effects of positivity during adulthood and emerging adulthood is flourishing (e.g., Ferreira et al., 2021), little is known about the association between positivity and mental health during childhood (e.g., Sette et al., 2022; Zuffianò et al., 2019) and adolescence (e.g., Malerba et al., 2022). In general, positivity seems to benefit adults’ well-being by reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms (Thartori et al., 2021). Optimism and trait positive affect have been associated with lower depression in emerging adults (e.g., Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). Even the few studies investigating the role of positivity in its relation to well-being in children showed similar results. For instance, in a cross-sectional study positivity moderated the relation between shyness and internalizing problems in school-age children (Sette et al., 2022). Regarding adolescence, in a longitudinal study, positivity moderated the relation between intolerance for uncertainty (reflecting difficulties in tolerating the unpleasant reactions elicited by uncertainty) and internalizing problems (encompassing social withdrawal, somatic complaints, anxiety, and depression) in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (Malerba et al., 2022). In particular, the authors found that higher positivity was related to a weaker relation between intolerance for uncertainty and internalizing problems. Understanding the contribution of positivity to adolescents’ mental health is particularly relevant during an emergency period characterized by remarkable stressful events and changes in daily routines. Indeed, positivity is crucial for adolescents to engage in positive reappraisal and planning as adaptive strategies (Jurisevic et al., 2021) and to cope effectively with dynamic and challenging events (Alessandri et al., 2012). Notably, positivity explains a substantial proportion of trait variance in ego-resiliency (Milioni et al., 2016), which refers to the capacity to adjust and cope with the demands of stressful events effectively (Malerba et al., 2022). Hence, it becomes evident that positivity can represent a key element in preserving adolescents’ mental health during the context of a global pandemic.

The widespread dissemination of the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a surge in sleep-related issues, particularly among children and adolescents (Bacaro et al., 2022; Bruni et al., 2022). Identifying the factors that could play a protective role against the negative impact of the pandemic on adolescents’ sleep quality is crucial for understanding and promoting well-being during challenging times. In particular, a positive orientation toward life is associated with higher resilience levels (Caprara et al., 2019), which, in turn, has been found to be related to better sleep quality and shorter sleep latency during adolescence (Wang et al., 2020). Moreover, having a positive outlook reduces stress levels (Troy & Mauss, 2011), often associated with poor sleep quality impairments (Casagrande et al., 2020). In other studies, the ability to generate a more positive interpretation of a stressful event, capable of altering its emotional impact (i.e., cognitive reappraisal), was found to be positively associated with better sleep quality (Mauss et al., 2013) and morning chronotype (Watts & Norbury, 2017), commonly linked to enhanced sleep duration and efficiency (Vitale et al., 2015). To date, a limited number of studies have investigated the relation between specific components of positivity (i.e., self-esteem, life satisfaction, dispositional optimism) and sleep quality. Weitzer et al. (2021) investigated the association between dispositional optimism and chronic insomnia in N = 1004 adults between 18 and 65 years of age. The authors found that showing greater optimism was linked to a reduced risk of chronic insomnia, regardless of potentially confounding factors (i.e., age, gender, SES, education, and work status). These findings align with previous research that showed negative relations between optimism and insomnia in college students (Sing & Wong, 2011), as well as between optimism and sleep latency in children (Lemola et al., 2011), with no emerging gender differences in the samples. Furthermore, poor sleep quality and the emergence of insomnia symptoms seem to be associated with reduced levels of self-esteem in university students (Lindsay et al., 2022) and lower levels of life satisfaction in children (Blackwell et al., 2020). To the best of our knowledge, no study has specifically addressed the link between positivity as a unique construct and sleep-related issues in samples of adolescents during the pandemic.

Age, gender, SES, and schooling modality as potential control variables

The pandemic had a complex impact on mental health, particularly in adolescents. Various demographic and context factors, such as age, gender, socio-economic status (SES), and schooling modality, might have significantly contributed to determining mental health outcomes during this period. Indeed, prior research has shown that psychological challenges like depression and anxiety escalated progressively during the pandemic, from late childhood to adolescence (e.g., Gruber et al., 2020). As underlined by Gruber et al. (2020), the heightened risk to adolescents’ well-being could stem from the substantial disruptions to their face-to-face interactions with peers, which are pivotal for emotional, moral, behavioral, and identity growth during adolescence. A lack of regular peer contact and sudden loss of autonomy could lead to considerable emotional distress, especially for that age group (i.e., adolescence), where these issues are particularly relevant. Thus, age represents a potentially relevant variable when investigating the determinants of adolescents’ well-being.

Gender differences have been observed, with females showing higher levels of mental health difficulties and loneliness (e.g., Ferreira et al., 2021), and lower levels of positivity than males (e.g., Alessandri et al., 2012). Some authors suggested that young females commonly employ rumination as a coping strategy for stress more often than males, leading to a subsequent decline in mental health (e.g., Hyde et al., 2008) and sleep quality (Pillai & Drake, 2015). Gender emerged as a critical factor for the effects on sleep-related issues in some studies with adults, with women generally experiencing poorer sleep quality (e.g., longer sleep latency and non-restorative sleep) than men across various countries during the pandemic (Pilcher et al., 2022; Pinto et al., 2020). However, research is limited in terms of providing evidence for gender differences in sleep-related issues among adolescents during the pandemic. Further, a recent research has indicated that individuals with lower income experienced a higher prevalence of mental health impairments than those with higher income levels (Pieh et al., 2020). Low-income individuals usually experience higher levels of financial stress, inadequate housing conditions, and limited access to mental health services, which, in turn, can lead to greater anxiety, depression, and other mental health challenges.

Finally, school closures and remote schooling modalities have disrupted the regular habits of 1.6 billion students (UNESCO, 2021). While scientific evidence may lack concordance regarding the actual magnitude of the impact of school closures, a growing body of research suggests that remote schooling may have been contributing to exacerbating stress and anxiety in youth, especially in those with a lower SES (e.g., Chaabane et al., 2021). Concerning sleep quality, previous studies reported mixed results on the effects of remote schooling. For instance, during the first months of the pandemic, the overall sleep quality remained unchanged. Still, time in bed increased by about two hours, and the levels of daytime sleepiness and frequency of napping tended to decrease (e.g., Santos & Louzada, 2022). Hence, students attending school in remote modality may have gained some advantage in their sleep duration at night (Rocha & Fuligni, 2023). Nonetheless, some other studies indicated that the advantages of sleep observed during the first months after the onset of the pandemic did not persist by the second wave of the pandemic (autumn 2020), with sleep time no longer significantly differing from the pre-pandemic period (e.g., Morrissey & Engel, 2023). Yet, later studies indicated that with the return to in-person or hybrid schooling modalities, between February and April 2021, a worsening in sleep quality occurred (e.g., Bacaro et al., 2022). Overall, it emerges as crucial to consider the potential impact of remote schooling while examining adolescents’ mental health and sleep quality during the pandemic, paying particular attention to the timing of data collection.

In summary, the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic led many countries worldwide to adopt school closure and remote schooling as preventive measures to promote social distancing and mitigate the dissemination of the virus. The strategies employed for remote schooling varied across the countries, evolving dynamically in response to the changing landscape of the pandemic and the unique emergency conditions faced by each nation (UNESCO, 2021). Given the essential human motivation to establish significant social connections, particularly relevant during the transition to adolescence (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), the issue of loneliness gained heightened significance amid the pandemic. Specifically, studies converge in highlighting increased levels of loneliness and social isolation due to social distancing (Branje & Morris, 2021; Farrell et al., 2023). In such context, individuating protective factors buffering the negative impact of social distancing becomes crucial. Positivity, intended as an inner disposition to interpret challenging events with a more positive outlook through self-reflection (Caprara et al., 2012), can play a role in promoting adolescents’ mental health (Caprara et al., 2019). However, there is limited knowledge regarding positivity in adolescents amid the pandemic (Malerba et al., 2022).

The prolonged stress, uncertainty, and social isolation brought about by the pandemic have contributed to heightening the levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and sleep-related issues (i.e., delayed bedtimes, poor sleep quality), particularly among young people (Richter et al., 2023; Santomauro et al., 2021; Zuccolo et al., 2023). Divergent findings on the impact of remote schooling during the pandemic emerged. While some studies indicated an increase in stress and anxiety levels for those attending remotely, particularly among lower SES youth (e.g., Chaabane et al., 2021), others showed mixed results regarding sleep quality. Initial advantages, such as extended sleep duration during remote learning (Rocha & Fuligni, 2023), may not have persisted into later stages of the pandemic (Bacaro et al., 2022). The literature highlights a need for further research to reconcile these discrepancies. Despite loneliness being a significant concern during that challenging time and its positive relation with mental health problems, there are gaps in understanding the potential role of other factors, such as homeschooling (Albrecht et al., 2022), and their influence on the loneliness-mental health association. Moreover, existing studies have predominantly focused on the association between loneliness and sleep quality in adults (Pilcher et al., 2022; Santini & Koyanagi, 2021). Notably, few studies had a specific focus on adolescents amid the pandemic, although scientific evidence suggests that heightened feelings of loneliness may be associated with sleep disruptions among youth (i.e., difficulty in falling asleep and staying asleep during the night; Becker et al., 2021; Dondi et al., 2021). Furthermore, while research on positivity’s beneficial effects in adulthood is abundant (Ferreira et al., 2021), limited attention has been given to its impact on mental health and sleep in adolescence, specifically focusing on the pandemic period. Some evidence suggests that positivity played a crucial role in moderating the relation between intolerance for uncertainty and internalizing problems (Malerba et al., 2022). Existing studies in adults also show a negative association between dispositional optimism and chronic insomnia (Weitzer et al., 2021), while poor sleep quality is associated with reduced self-esteem in university students (Lindsay et al., 2022) and diminished life satisfaction in children (Blackwell et al., 2020). Further investigation is needed to better understand the link between positivity, in all its components, and adolescents’ mental health and sleep quality during this emergency period.

Finally, some studies revealed gender to play an important role, with females tending to exhibit elevated levels of mental health difficulties and loneliness (e.g., Ferreira et al., 2021) and lower levels of positivity than males (e.g., Alessandri et al., 2012). In certain studies, gender emerged as a crucial factor influencing sleep-related issues, with women generally reporting poorer sleep quality, including longer sleep latency, compared to men during the pandemic (Pilcher et al., 2022; Pinto et al., 2020). Although there is scientific evidence regarding these phenomena among adults, research on adolescents is still lacking. Specifically, there is limited scientific evidence to determine whether gender differences played a role in the links between loneliness/positivity and mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues among adolescents during the pandemic.

The current study

In light of the studies conducted so far and willing to fill the persistent gaps, the present study aimed to understand the potential role of loneliness and positivity in the association with adolescents’ mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues during the COVID-19 pandemic. These relations were investigated controlling by potentially relevant confounding variables, including age, gender, SES, and schooling modality. On a more exploratory basis, we examined differences in the associations among positivity/loneliness and mental health difficulties/sleep-related issues as a function of gender, age, SES, and schooling modality. To meet these aims, we formulated the following hypotheses:

-

1.

Loneliness would be positively associated with all indices of mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues.

-

2.

Positivity would be negatively related to mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues.

-

3.

Older age, being female, and coming from families with lower SES, would be positively associated with mental health impairments and poor sleep quality. Attending school in-person would be positively associated with better mental health, while remote attendance would be positively related to aspects of improved sleep quality.

-

4.

On the basis of extant literature, positivity would be associated with a decrease in mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues in females and adolescents with a lower SES. Loneliness would be related to an increase in mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues in females.

Method

Participants

Participants were N = 564 adolescents (48.9% females) aged between 13 and 18 years (Mage = 15.86, SD = 1.41) enrolled in secondary schools in a large metropolitan center in Italy. The inclusion criteria of students were to: a) attend a secondary school; and b) understand the Italian language (for students with a migratory background). The majority of the sample (97.5%, n = 550) was born in Italy, with the remaining respondents born in East Europe (1.1%, n = 6), Asia (0.3%, n = 2), Central America (0.3%, n = 2), Africa (0.2, n = 1), and North America (0.2%, n = 1); for two participants data were missing. Socio-Economic Status (SES) was predominantly from the middle (77.9%, n = 434) to upper-middle (19.3%, n = 109) classes.

Procedure

After obtaining informed consent from parents and participants, we asked students to complete an online questionnaire assessing their socio-emotional functioning using a laptop/phone/other with an internet connection. The survey was conducted between February and May 2021, when educational policies set up blended schooling modalities involving in-person classes and remote learning. In the current study, we considered measures that assessed loneliness, positivity, mental health difficulties, and sleep-related issues. We collected data using the Qualtrics survey tool.

Measures

Loneliness

We assessed Loneliness via a shortened version of the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1978; for the use of the scale in Italy, see Boffo et al., 2012), which measures subjective feelings of loneliness and social isolation. We included four items (e.g., “I feel isolated from others”) to reduce the study burden for participants. The shortened version of this measure was used in previous studies (e.g., Eccles et al., 2020), demonstrating to be appropriate for investigating loneliness in adolescents. Participants rated each item on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (I never feel this way) to 3 (I often feel this way). Reliability for this measure’s short version was good (α = 0.85).

Positivity

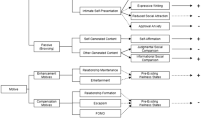

We used the Positivity scale (Caprara et al., 2012) to assess the tendency to evaluate own life and experiences with a positive orientation. The scale included eight items (e.g., “I look to the future with hope and optimism”) on self-esteem, optimism, and life satisfaction. Participants rated each item on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Reliability for this scale was good (α = 0.78).

Mental health difficulties

To assess mental health difficulties, we used the following scales:

-

(1)

General health problems. We used the General Health Questionnaire – 12 (GHQ-12; Goldberg et al., 1997; Fraccaroli et al., 1991) to evaluate adolescents’ psychological difficulties and strains. This scale is composed of twelve items (e.g., “Have you recently been able to concentrate on whatever you’re doing?”), each rated through a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (significantly less than usual) to 3 (more than usual). The reliability of the scale was good (α = 0.86).

-

(2)

Stress. We administered the Stress subscale of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale – 21 (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). This instrument included seven items (e.g., “I found it difficult to relax”) to be rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (doesn’t apply to me at all) to 4 (applies a lot or most of the time to me). The reliability of the scale was good (α = 0.89).

Sleep-related issues

We used the Italian version of the School Sleep Habits Survey (Wolfson et al., 2003), which included:

-

(1)

Open questions about the habitual bedtime and rise time, from which we computed the total sleep time, as well as sleep latency (“How long does it usually take you to fall asleep?”). The sleep latency was coded through six categories of response (1 = 0 to 5 min, 2 = 6 to 15 min, 3 = 16 to 30 min, 4 = 31 to 45 min, 5 = 46 to 60 min, and 6 = more than one hour; see also Bruni et al., 2015).

-

(2)

Sleep–Wake Problems Behavior Scale (SWPBS). We used this measure to assess sleep problems, such as difficulties waking up in the morning and night awakenings. The scale is composed of fifteen items, but we used a shortened version of eight items to reduce participants’ testing time and fatigue. Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The reliability of the scale was good (α = 0.74).

Control variables

Socio-demographic information

Participants provided information on their age, gender (0 = male, 1 = female), and place of birth, the migratory background of students and their parents (i.e., where they and their parents were born), and SES of families (i.e., “How would you define your SES condition?”), responding on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (extremely low) to 5 (extremely high).

Schooling modality

Participants were asked whether they attended school fully in-person, fully remotely, or in a hybrid modality (i.e., both in-person and remotely) at the time of survey completion. We computed two dummy variables based on participants’ responses to capture the contribution of the three-category group variable (i.e., in-person, hybrid, and remote schooling). For the first dummy variable, named in-person schooling, we assigned in-person modality a value of “1” and other modalities a value of “0”. For the second dummy variable, named in-person and hybrid schooling, we assigned both in-person and hybrid modalities a value of “1”, whereas remote schooling a value of “0”.

Plan of the analysis

We conducted all analyses using SPSS 27. We performed zero-order correlations to evaluate the relationships among all key variables with age, gender, SES, and schooling modalities. Next, we conducted a series of hierarchical linear regressions to assess the role of positivity and loneliness on indices of (i) mental health difficulties (i.e., general health problems and stress) and (ii) sleep-related issues (i.e., sleep problems, sleep latency, and sleep time). In the first step, we included gender, age, SES, and schooling modalities as covariates. In the second step, we entered positivity and loneliness to investigate their contribution to the indices of mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues. Finally, on an exploratory basis, to evaluate the role of age, gender, SES, and schooling modality as potential moderators of these associations, we tested the role of two-way interaction terms involving these control variables (e.g., gender × positivity, gender × loneliness) on outcome variables (mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues). We mean-centered all continuous independent variables (Cohen et al., 2002) and hierarchical multiple regressions were repeated separately for each outcome.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Overall, regarding schooling modalities, 57 adolescents (10.2%) attended school remotely, 181 adolescents (32.3%) attended school in-person, and 336 adolescents (57.6%) attended in a hybrid modality. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and associations among the study variables. Results revealed that positivity was negatively associated with mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues, and positively related to sleep time. Loneliness was positively associated with mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues, as well as negatively related to sleep time. All mental health difficulties and sleep variables were significantly correlated in the expected directions, with both general health problems and stress positively relating to sleep problems and sleep latency and negatively relating to sleep time. Notably, both age and gender, as well as SES and schooling modalities, showed significant correlations with our outcomes. For instance, with age increases, participants reported higher mental health difficulties and sleep problems. In addition, females displayed lower mean values of positivity and higher mean values of loneliness. SES showed a positive association with positivity and a negative association with loneliness. Adolescents attending school in a hybrid modality presented higher mean values on mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues than adolescents attending in-person and remotely.

The role of loneliness and positivity on indices of mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues

Table 2 reports the results of the hierarchical regression analyses with indices of mental health difficulties as dependent variables. More in detail, results with general health problems as the dependent variable revealed that positivity was negatively associated with general health problems, whereas loneliness was positively related to general health problems. Gender was also significant, whereby females reported higher general health problems than males. Moreover, adolescents attending school with an in-person modality reported significantly lower scores on general health problems than those attending in remote and hybrid modalities.

Similar results emerged from the hierarchical regression analysis with stress as the dependent variable. We found a significant negative association between positivity and stress and a significant positive relation between loneliness and stress. Gender was also significant, indicating that females reported higher stress levels than males.

Table 3 reports the results of the hierarchical regressions with indices of sleep-related issues as dependent variables. Findings with sleep problems as the dependent variable showed that positivity was negatively associated with the outcome, whereas loneliness was positively related to sleep problems. Both age and gender were significant. These results indicated that older adolescents and females reported significantly higher scores on sleep problems than younger adolescents and males, respectively. Finally, adolescents attending school in-person and with a hybrid modality reported significantly higher scores on sleep problems than adolescents attending remotely.

Results from the hierarchical regression analysis with sleep latency as the dependent variable indicated only a significant negative association with positivity and a significant positive relation with gender, meaning that females reported greater difficulties in falling asleep than males.

Finally, results with sleep time as the dependent variable showed that positivity was positively related to the oucome. A negative relation between age and sleep time was also found. Older adolescents reported sleeping fewer hours during the nighttime than their younger counterparts. Adolescents attending school in-person reported significantly higher sleep time scores than those attending in hybrid and remote modalities. On the contrary, adolescents attending school in-person and with a hybrid modality reported significantly lower sleep time scores than those attending remotely. In other words, results revealed that adolescents who attended with a hybrid modality reported lower sleep time scores than those attending with in-person and remote modalities.

The moderating role of age, gender, ses, and schooling modality

Regarding the potential moderating role of control variables (i.e., age, gender, SES, and schooling modality), we only found a significant two-way interaction term gender × positivity in the regression analysis with sleep latency as the dependent variable (see Fig. 1). Specifically, results revealed a significant negative association between positivity and sleep latency, F(8, 519) = 5,90, p < 0.001, for females (b = -0.48, SE = 0.12, p < 0.001) but not for males (b = -0.03, SE = 0.12, p = 0.78). Therefore, only for females positivity could help reduce latency before falling asleep. No other significant two-way interaction terms involving gender, age, SES, and schooling modality in the association with sleep latency emerged. Overall, the model explained 7% of the variance in sleep latency. For the other dependent variables, we did not find significant two-way interaction terms involving gender, age, SES, and schooling modality.

Discussion

The role of loneliness and positivity

The current study examined whether loneliness and positivity might have a role in adolescents’ mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although examining the risk and protective factors that can impact adolescents’ well-being is of utmost interest to researchers and practitioners, scientific evidence is still limited.

Overall, loneliness was related to more severe mental health impairments and sleep problems, whereas positivity played a protective role against both mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues, the latter especially for females. Gender, age, and schooling modality showed significant associations with our outcomes. For instance, females showed higher mental health difficulties, higher sleep problems, and longer sleep latency than males, whereas older adolescents presented higher sleep problems and shorter sleep time. Interestingly, the hybrid schooling modality emerged as the factor that negatively impacted adolescents’ sleep quality.

More in detail, loneliness was positively associated with mental health impairments, even when controlling for socio-demographic characteristics and schooling modality. This provides further support to previous research indicating a heightened risk of mental health problems for those who reported higher loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Farrell et al., 2023; Santini & Koyanagi, 2021). As it appears clear in Farrell et al’s (2023) systematic review, strong associations emerged from cross-sectional studies using correlational and multivariate regression analyses. In particular, adolescents showing higher loneliness and social isolation also presented higher depression and anxiety symptoms and more impaired overall well-being and mental health. Also, loneliness can contribute to the onset of depressive and anxiety symptoms of adolescents, with potentially long-lasting effects extending over several years. For instance, Loades et al. (2020) showed that the effects of loneliness on children’s and adolescents’ mental health can last up until 9 years later. Feeling socially isolated or having limited social interactions and support, less than one desires can affect individuals’ emotional state, leading to feelings of worthlessness and anxiety. Therefore, the need to implement interventions targeting adolescents’ feelings of loneliness becomes evident to address and mitigate their potential negative impact on mental health. Loneliness was also associated with adolescents’ sleep problems, in line with other research (e.g., Dondi et al., 2021), indicating that those who felt less connected with friends and peers reported more sleep disturbances, including feeling tired or sleepy during the day, having nightmares, and waking up during the night. However, we did not find significant relations between loneliness and sleep latency or total sleep time. It is possible that our measure of loneliness did not capture aspects that could be more relevant to the difficulties before falling asleep and sleep duration. Indeed, as highlighted by previous findings (e.g., Eccles et al., 2020), the association between loneliness and sleep disturbances can vary in strength across different ages and depending on the specific assessment instruments employed in the study.

Positivity was significantly associated with all our mental health and sleep outcomes in the expected directions, thus supporting our hypotheses regarding the protective role of positivity in relation to adolescents’ well-being. During an emergency period characterized by dramatic changes in daily routines, terrible news from all around the world, and uncertainty about the future, it is reasonable that adolescents with higher optimism and a more positive outlook on life (Caprara et al., 2012) were more likely to display greater well-being (Alessandri et al., 2012; Weitzer et al., 2021). As shown in other studies (e.g., Jurisevic et al., 2021; Mauss et al., 2013), positivity can stimulate positive reappraisal and refocus on planning, which can be effective strategies to face an emergency situation. Nonetheless, research on the link between positivity as a unique construct and adolescents’ well-being is still limited. The emphasis has mainly been on adults or specific aspects of positivity (e.g., Blackwell et al., 2020; Lindsay et al., 2022; Weitzer et al., 2021). Of particular interest were the associations we found between positivity and sleep-related issues. Controlling for age, gender, SES, and schooling modality, positivity was negatively associated with sleep problems and positively associated with sleep time at night. It is possible that approaching life with a positive disposition during such a challenging period can help reframe negative thoughts and reduce stress levels, making it easier to relax and allowing for better sleep (Troy & Mauss, 2011). Interestingly, we found that sleep latency before falling asleep was shorter for females with higher positivity, but not for males. This means positivity only prevented sleep disturbances for females, who showed particular difficulties in falling asleep at night. One possible explanation may be that, as shown in prior research (e.g., Hyde et al., 2008), adolescent females tend to use ruminative strategies to cope with stress more frequently than males, which, in turn, contributes to compromised sleep quality (e.g., Pillai & Drake, 2015). Therefore, a more optimistic perspective on life could help contrast negative thoughts and promote better sleep quality. However, as far as we know, no other study has investigated the role of positivity on adolescents’ sleep quality, and further investigation is needed.

The role of socio-demographic variables and schooling modality

Notably, from both correlational and regression analyses, females emerged as more impaired than their male counterparts on all our indices, reporting lower scores on positivity and higher scores on loneliness, mental health difficulties, stress, sleep problems, and longer sleep latency. These gender differences were in line with previous findings, showing that positivity is generally higher in males (e.g., Alessandri et al., 2012), whereas mental health difficulties and sleep-related problems are more frequent in females (e.g., Ferreira et al., 2021; Santomauro et al., 2021). Importantly, our study extends this understanding to the specific context of an emergency period, emphasizing the intensified impact on the well-being of adolescents grappling with the challenges imposed by the pandemic.

We also found that age was a relevant variable related to our outcomes. In particular, older adolescents showed higher mental health difficulties, sleep problems, and shorter sleep time than younger adolescents. From prior research (e.g., Gruber et al., 2020), we know that psychological impairments, such as depression and anxiety, progressively increase from late childhood throughout adolescence. Compared to earlier stages of development, later adolescents may rely more on external coping mechanisms, such as social activities or extracurricular pursuits, which were restricted during the pandemic. Further, later adolescents are in a critical stage of social development, seeking autonomy while forming strong peer relationships. Therefore, older adolescents may have faced particular challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Further, adolescents from families with higher SES scored higher in positivity and lower in loneliness and mental health difficulties, as reported in other studies (Pieh et al., 2020). It is likely that adolescents from low-income families might have faced greater challenges in accessing essential resources for mental health support or might have experienced higher levels of family tension due to financial hardships, which could have negatively affected their mental health and positivity.

Finally, consistent with previous research (e.g., Chaabane et al., 2021), adolescents who attended school in-person showed fewer mental health difficulties, whereas a novel finding emerged concerning the sleep-related issues, with those who attended school in the hybrid modality exhibiting greater problems than those who attended entirely remotely or in-person. This result emerged from both correlational and regression analyses. While some improvement in sleep quality (e.g., a two-hour increase at night) was observed in the initial phases of the pandemic (Santos & Louzada, 2022), subsequent studies (e.g., Morrissey & Engel, 2023) indicated that these sleep enhancements were not sustained into the second wave. Furthermore, Bacaro et al. (2022) found that returning to in-person or hybrid schooling models between February and April 2021 was associated with a decline in sleep quality. Therefore, in partial alignment with the latter study, our findings suggest that adopting a hybrid approach to attending classes may disrupt students’ daily routines to a greater extent than other modalities during the advanced phases of the pandemic. We argue that constantly changing their weekly schedules may have prevented adolescents from establishing consistent and adequate sleep routines. Further studies should be conducted to gain a deeper understanding of the consequences associated with the different modalities of school attendance during diverse phases of the pandemic.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

The present study has the merit to provide data on the potential risk and protective factors associated with adolescents’ mental health and sleep disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic in a vulnerable but understudied developmental period (e.g., Loades et al., 2020; Rocha & Fuligni, 2023). This topic is highly relevant and lacking in extensive research, making the current study particularly relevant. Limited research exists on the relationship between adolescents’ loneliness and well-being during the pandemic (e.g., Farrell et al., 2023), and no studies have yet explored the association between positivity and sleep. Notably, adolescence is a developmental period characterized by dramatic changes in many domains of the self (Havighurst, 1972). Therefore, studying the determinants of mental health and sleep quality of this specific developmental phase during an emergency that restricted social interactions and disrupted daily routines is particularly valuable. We also included variables (i.e., gender, age, SES, schooling modality) that, based on prior research (e.g., Chaabane et al., 2021; Pieh et al., 2020), could potentially impact our outcomes.

Despite these strengths, our study is not without limits. First, we collected cross-sectional data, thus limiting our plan of analysis in its ability to examine the causal effects on adolescents’ well-being. Second, we did not collect data before the onset of the pandemic. Thus, we could not measure changes in the indices of adolescents’ well-being from the pre-and post-pandemic periods. Moreover, we analyzed data from an adolescent sample in Italy, where specific preventive measures were implemented, tailored to the particular phase of the pandemic. It is important to note that participants in our study were in a blended schooling modality at the time of data collection, with 10.2% of adolescents reporting attending school remotely, 57.6% attending in a hybrid modality (i.e., partly in-person and partly remotely), and 32.3% attending school in-person. Therefore, our findings may not apply to other adolescent samples in different countries that have implemented diverse measures (e.g., fully in-person, fully remotely) to restrain the spread of the virus, depending on their contagion rates. Third, we included only online self-report questionnaires, which are susceptible to response biases and subjective interpretation. Therefore, future research could employ longitudinal designs and a multi-method (e.g., observational data, objective measures) and multi-informant (e.g., parents, teachers) approach to enhance the validity and reliability of study findings.

In conclusion, loneliness significantly contributed to severe mental health difficulties and sleep problems. In contrast, positivity served a protective function against both mental health difficulties and sleep-related issues. We believe that studying the factors contributing to adolescents’ psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic can provide crucial knowledge for developing effective interventions with youth to counter the negative contribution of loneliness and enhance positivity, which represents a fundamental resource to use, especially when facing extreme adverse events. In particular, drawing from prior research, interventions should focus on facilitating the acquisition of effective strategies to boost perceived social support (e.g., Wang et al., 2018), as well as integrated approaches that enhance social and emotional skills (e.g., Christiansen et al., 2021).

Data availability

The dataset for this original article has been uploaded as online supplemental material.

References

Albrecht, J. N., Werner, H., Rieger, N., Widmer, N., Janish, D., Huber, R., & Jenni, O. (2022). Association between homeschooling and adolescent sleep duration and health during COVID-19 pandemic high school closures. JAMA Network Open, 5(1), e2142100. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42100

Alessandri, G., Caprara, G. V., & Tisak, J. (2012). A unified latent curve, latent state-trait analysis of the developmental trajectories and correlates of positive orientation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 47(3), 341–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2012.673954

Bacaro, V., Meneo, D., Curati, S., Buonanno, C., De Bartolo, P., Riemann, D., Mancini, F., Martoni, M., & Baglioni, C. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on Italian adolescents’ sleep and its association with psychological factors. Journal of Sleep Research, 31(6), e13689. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13689

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. Harper & Row.

Becker, S. P., Dvorsky, M. R., Breaux, R., Cusick, C. N., Taylor, K. P., & Langberg, J. M. (2021). Prospective examination of adolescent sleep patterns and behaviors before and during COVID-19, Sleep, 44(8), zsab054. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsab054

Blackwell, C. K., Hartstein, L. E., Elliott, A. J., Forrest, C., Ganiban, J., Hunt, K. J., Camargo, C. A., Jr., & LeBourgeois, M. K. (2020). Better sleep, better life? How sleep quality influences children’s life satisfaction. Quality of Life Research, 29, 2465–2474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02491-9

Boffo, M., Mannarini, S., & Munari, C. (2012). Exploratory structure equation modeling of the UCLA loneliness scale: A contribution to the Italian adaptation. Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 19(4), 345–363. https://doi.org/10.4473/TPM19.4.7

Branje, S., & Morris, A. S. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent emotional, social, and academic adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 486–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12668

Bruni, O., Sette, S., Fontanesi, L., Baiocco, R., Laghi, R., & Baumgartner, E. (2015). Technology use and sleep quality in preadolescence and adolescence. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(12), 1433–1441. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.5282

Bruni, O., Malorgio, E., Doria, M., Finotti, E., Spruyt, K., Melegari, M. G., Villa, M. P., & Ferri, R. (2022). Changes in sleep patterns and disturbances in children and adolescents in Italy during the Covid-19 outbreak. Sleep Medicine, 91, 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.02.003

Bukowski, W. M., Simard, M., Dubois, M. E., & Lopez, L. S. (2011). Representations, Process, and Development: A New Look at Friendship in Early Adolescence. In E. Amsel & J. Smetana (Eds.), Adolescent vulnerabilities and opportunities: Developmental and constructivist perspectives (interdisciplinary approaches to knowledge and development, pp. 159–181). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139042819.010

Caprara, G. V., Alessandri, G., Eisenberg, N., Kupfer, A., Steca, P., Caprara, M. G., Yamaguchi, S., Fukuzawa, A., & Abela, J. (2012). The positivity scale. Psychological Assessment, 24(3), 701–712. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026681

Caprara, G. V., Alessandri, G., & Caprara, M. (2019). The associations of positive orientation with health and psychosocial adaptation: A review of findings and perspectives. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 22(2), 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12325

Casagrande, M., Favieri, F., Tambelli, R., & Forte, G. (2020). The enemy who sealed the world: Effects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population. Sleep Medicine, 75, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.011

Chaabane, S., Doraiswamy, S., Chaabna, K., Mamtani, R., & Cheema, S. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 school closure on child and adolescent health: A rapid systematic review. Children, 8(5), 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8050415

Christiansen, J., Qualter, P., Friis, K., Pedersen, S. S., Lund, R., Andersen, C. M., Bekker-Jeppesen, M., & Lasgaard, M. (2021). Associations of loneliness and social isolation with physical and mental health among adolescents and young adults. Perspectives in Public Health, 141(4), 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/17579139211016077

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2002). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed. ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203774441

Cooper, K., Hards, E., Moltrecht, B., Reynolds, S., Shum, A., McElroy, E., & Loades, M. (2021). Loneliness, social relationships, and mental health in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 289, 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.016

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Dondi, A., Fetta, A., Lenzi, J., Morigi, F., Candela, E., Rocca, A., Cordelli, D. M., & Lanari, M. (2021). Sleep disorders reveal distress among children and adolescents during the Covid-19 first wave: Results of a large web-based Italian survey. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 47, 130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-021-01083-8

Eccles, A. M., Qualter, P., Madsen, K. R., & Holstein, B. E. (2020). Loneliness in the lives of Danish adolescents: Associations with health and sleep. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 48(8), 877–887. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494819865429

Farrell, A. H., Vitoroulis, I., Eriksson, M., & Vaillancourt, T. (2023). Loneliness and well-being in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A systematic review. Children, 10(2), 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020279

Ferreira, M. J., Sofia, R., Carreno, D. F., Eisenbeck, N., Jongenelen, I., & Cruz, J. F. A. (2021). Dealing with the pandemic of COVID-19 in Portugal: On the important role of positivity, experiential avoidance, and coping strategies. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 647984. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647984

Fraccaroli, F., Depolo, M., & Sarchielli, G. (1991). The use of Goldberg’s General Health Questionnaire in a young unemployed sample. Bollettino Di Psicologia Applicata, 197, 13–19.

Goldberg, D. P., Gater, R., Sartorius, N., Ustun, T. B., Piccinelli, M., Gureje, O., & Rutter, C. (1997). The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291796004242

Gruber, J., Prinstein, M. J., Clark, L. A., Rottenberg, J., Abramowitz, J. S., Albano, A. M., Aldao, A., Borelli, J. L., Chung, T., Davila, J., Forbes, E. E., Gee, D. G., Nagayama Hall, G. C., Hallion, L. S., Hinshaw, S. P., Hofmann, S. G., Hollon, S. D., Joormann, J., Kazdin, A. E., Klein, D. N., … Weinstock, L. M. (2020). Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID-19: Challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. American Psychologist, 76(3), 409–426. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000707

Havighurst, R. J. (1972). Developmental tasks and education. David McKay.

Hyde, J. S., Mezulis, A. H., & Abramson, L. Y. (2008). The ABCs of depression: Integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychological Review, 115(2), 291–313. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.291

Jurisevic, M., Lavrih,L., Lisic, A., Podlogar, N., Zerak, U. (2021). Higher education students’ experience of emergency remote teaching during the Covid-19 pandemic in relation to self-regulation and positivity. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 11, 241–262. https://doi.org/10.26529/cepsj.1147

Laursen, B., & Hartl, A. C. (2013). Understanding loneliness during adolescence: Developmental changes that increase the risk of perceived social isolation. Journal of Adolescence, 36(6), 1261–1268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.06.003

Lemola, S., Räikkönen, K., Scheier, M. F., Matthews, K. A., Pesonen, A. K., Heinonen, K., Lahti, J., Komsi, N., Paavonen, J. E., & Kajantie, E. (2011). Sleep quantity, quality and optimism in children. Journal of Sleep Research, 20(1 Pt 1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2010.00856.x

Lindsay, J. A. B., McGowan, N. M., King, N., Rivera, D., Li, M., Byun, J., Cunningham, S., Saunders, K. E. A., & Duffy, A. (2022). Psychological predictors of insomnia, anxiety and depression in university students: Potential prevention targets. Bjpsych Open, 8(3), e86. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.48

Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A., Linney, C., McManus, M. N., Borwick, C., & Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218-1239.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803

Magson, N. R., Freeman, J. Y. A., Rapee, R. M., Richardson, C. E., Oar, E. L., & Fardouly, J. (2021). Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9

Malerba, A., Iannattone, S., Casano, G., Lauriola, M., & Bottesi, G. (2022). The trap of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Italian adolescents farewell at first, maybe thanks to protective trait expression. Children, 9(11), 1631. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111631

Mauss, I. B., Troy, A. S., & LeBourgeois, M. K. (2013). Poorer sleep quality is associated with lower emotion-regulation ability in a laboratory paradigm. Cognition & Emotion, 27(3), 567–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2012.727783

Milioni, M., Alessandri, G., Eisenberg, N., & Caprara, G. V. (2016). The role of positivity as predictor of ego-resiliency from adolescence to young adulthood. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 306–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.025

Morrissey, A. W., & Engel, K. (2023). Adolescents’ time during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the American Time Use Survey. Journal of Adolescent Health, 72(2), 295–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.08.018

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. (1982). Perspectives on loneliness. In L. Peplau & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 1–18). John Wiley and Sons.

Pieh, C., Budimir, S., & Probst, T. (2020). The effect of age, gender, income, work, and physical activity on mental health during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in Austria. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 136, 110186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110186

Pilcher, J. J., Dorsey, L. L., Galloway, S. M., & Erikson, D. N. (2022). Social isolation and sleep: Manifestation during COVID-19 quarantines. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 810763. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.810763

Pillai, V., & Drake, C. L. (2015). Sleep and repetitive thought: The role of rumination and worry in sleep disturbance. In K. A. Babson, & M. T. Feldner (Eds.), Sleep and affect: Assessment, theory, and clinical implications (pp. 201–225). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-417188-6.00010-4-4

Pinto, J., van Zeller, M., Amorim, P., Pimentel, A., Dantas, P., Eusébio, E., Neves, A., Pipa, J., Santa Clara, E., Santiago, T., Viana, P., & Drummond, M. (2020). Sleep quality in times of Covid-19 pandemic. Sleep Medicine, 74, 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.07.012

Qamar, S., & Yaqoob, N. (2023). Positivity level predicts better health and mental health among adults. Journal of Current Health Sciences, 3(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.47679/jchs.202345

Richter, S. A., Ferraz-Rodrigues, C., Schilling, L. B., Camargo, N. F., & Nunes, M. L. (2023). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on sleep quality in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sleep Research, 32(1), e13720. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13720

Rocha, S., & Fuligni, A. (2023). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent sleep behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 101648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101648

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400876136

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Ferguson, M. L. (1978). Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42(3), 290–294. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11

Samji, H., Wu, J., Ladak, A., Vossen, C., Stewart, E., Dove, N., Long, D., & Snell, G. (2022). Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth–a systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 27(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12501

Santini, Z. I., & Koyanagi, A. (2021). Loneliness and its association with depressed mood, anxiety symptoms, and sleep problems in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 33(3), 160–163. https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2020.48

Santomauro, D. F., Mantilla Herrera, A. M., Shadid, J., Zheng, P., Ashbaugh, C., Pigott, D. M., Abbafati, C., Adolph, C., Amlag, J. O., Aravkin, A. Y., Bang-Jensen, B. L., Bertolacci, G. J., Bloom, S. S., Castellano, R., Castro, E., Chakrabarti, S., Chattopadhyay, J., Cogen, R. M., Collins, J. K., … Ferrari, A. J. (2021). Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 398, 1700–1712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7

Santos, J. S., & Louzada, F. M. (2022). Changes in adolescents’ sleep during COVID-19 outbreak reveal the inadequacy of early morning school schedules. Sleep Science, 15(1), 74–79. https://doi.org/10.5935/1984-0063.20200127

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1993). On the power of positive thinking: benefits of being optimistic. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2(1), 26–30. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20182190ep10770572

Sette, S., Zuffianò, A., López-Pérez, B., McCagh, J., Caprara, G. V., & Coplan, R. J. (2022). Links between child shyness and indices of internalizing problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: The protective role of positivity. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 183(2), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2021.2011093

Sing, C. Y., & Wong, W. S. (2011). The effect of optimism on depression: The mediating and moderating role of insomnia. Journal of Health Psychology, 16(8), 1251–1258. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105311407366

Thartori, E., Pastorelli, C., Cirimele, F., Remondi, C., Gerbino, M., Basili, E., Favini, A., Lunetti, C., Fiasconaro, I., & Caprara, G. V. (2021). Exploring the protective function of positivity and regulatory emotional self-efficacy in time of pandemic COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413171

Troy, A. S., & Mauss, I. B. (2011). Resilience in the face of stress: Emotion regulation as a protective factor. In S. M. Southwick, B. T. Litz, D. Charney & M. J. Friedman (Eds), Resilience and mental health: Challenges across the lifespan (Chapter 2, pp. 30 – 44). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511994791.004

UNESCO. (2021). Global monitoring of school closures. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse#durationschoolclosures (accessed on 27 June 2023).

Vitale, J. A., Roveda, E., Montaruli, A., Galasso, L., Weydahl, A., Caumo, A., & Carandente, F. (2015). Chronotype influences activity circadian rhythm and sleep: Differences in sleep quality between weekdays and weekend. Chronobiology International, 32(3), 405–415. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2014.986273

Wang, J., Mann, F., Lloyd-Evans, B., Ma, R., & Johnson, S. (2018). Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5

Wang, J., Zhang, X., Simons, S. R., Sun, J., Shao, D., & Cao, F. (2020). Exploring the bi-directional relationship between sleep and resilience in adolescence. Sleep Medicine, 73, 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.04.018

Watts, A. L., & Norbury, R. (2017). Reduced effective emotion regulation in night owls. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 32(4), 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748730417709111

Weitzer, J., Papantoniou, K., Lázaro-Sebastià, C., Seidel, S., Klösch, G., & Schernhammer, E. (2021). The contribution of dispositional optimism to understanding insomnia symptomatology: Findings from a cross-sectional population study in Austria. Journal of Sleep Research, 30(1), e13132. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13132

Wolfson, A. R., Carskadon, M. A., Acebo, C., Seifer, R., Fallone, G., Labyak, S. E., & Martin, J. L. (2003). Evidence for the validity of a sleep habits survey for adolescents. Sleep, 26(2), 213–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/26.2.213

Zuccolo, P. F., Casella, C. B., Fatori, D., Shephard, E., Sugaya, L., Gurgel, W., Farhat, L. C., Argeu, A., Teixeira, M., Otoch, L., & Polanczyk, G. V. (2023). Children and adolescents’ emotional problems during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(6), 1083–1095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02006-6

Zuffianò, A., López-Pérez, B., Cirimele, F., Kvapilová, J., & Caprara, G. V. (2019). The Positivity Scale: Concurrent and factorial validity across late childhood and early adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 831. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00831

Zuffianò, A., Caprara, G., Zamparini, M., Calamandrei, G., Candini, V., Malvezzi, M., Scherzer, M., Starace, F., Zarbo, C., & De Girolamo, G. (2023). The role of ‘Positivity’ and Big Five Traits during the COVID-19 pandemic: An Italian national representative survey. Journal of Happiness Studies, 24, 2813–2830. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-023-00705-8

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their thanks to schools and adolescents (with their respective families) who participated in the present study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The present study was funded by Sapienza University of Rome [grant number RM12117A8AE3B2CC, 2021].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Developmental and Social Psychology, Sapienza University, Rome.

Informed consent

All participants were informed of the purpose of the study and signed informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pecora, G., Laghi, F., Baumgartner, E. et al. The role of loneliness and positivity on adolescents’ mental health and sleep quality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05805-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05805-z