Abstract

Infrahumanization means considering the other or the outgroup as less human than oneself or the ingroup. However, little attention has been given to the variables that determine the selection of which outgroups may be subjected to infrahumanization and the variables that might be moderating this process. This research aims to analyze the role that the relationship with the outgroup plays in the attribution of secondary emotions and the moderator role of organizational dehumanization. Participants (N = 338 students) completed a structured questionnaire that took 15 min. The results show that there is an attribution of humanity to the outgroup when the relationship between ingroup and outgroup is closer. Furthermore, organizational dehumanization had a moderator role between the relationship with the outgroup and the infrahumanization, which shows that when the ingroup perceives that it is being dehumanized by its organization, it attributes less humanity to the outgroup. Our research extends the theoretical understanding of infrahumanization and suggests that the relationship between the outgroup and the organizational dehumanization impacts the attribution of humanity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infrahumanization, the subtle perception of out-group members as less human than ingroup members, is crucial due to its prevalence and impact on intergroup relations. It provides insights into how individuals dehumanize others, who are dehumanized, and the situational factors promoting such perceptions (Haslam and Loughnan, 2014; Leyens et al., 2000).

The study of infrahumanization is crucial in intergroup relations. However, there is a gap in understanding how the relationship with the outgroup affects infrahumanization and how organizational dehumanization moderates this relationship. While infrahumanization has been shown to be robust across many intergroup contexts (Delgado Rodríguez et al., 2012), little is known about how organizational characteristics, such as organizational dehumanization, may influence this phenomenon (Arriagada-Venegas et al., 2021a, 2021b; Cheung, 2023). Moreover, while it has been shown that helping the outgroup can reduce infrahumanization (Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2011), it is unclear how this dynamic interacts with organizational dehumanization. Therefore, your study will address these critical gaps, providing a deeper understanding of the factors influencing infrahumanization and how it can be mitigated in an organizational context.

From a theoretical, infrahumanization stands as a fundamental phenomenon in intergroup relations. Understanding how the outgroup relationship influences infrahumanization and how organizational dehumanization moderates this connection can offer valuable insights into intergroup dynamics. Moreover, it can aid in developing more comprehensive and nuanced theories regarding infrahumanization and dehumanization within organizational contexts. In relation to practical, infrahumanization can yield detrimental consequences, encompassing discrimination and unfair treatment (Castano & Giner-Sorolla, 2006; Cuddy et al., 2007; Rudman & Mescher, 2012). Grasping methods to mitigate infrahumanization can assist organizations in fostering fairer and more equitable work environments. Additionally, it can equip decision-makers with tools to address discrimination and advocate for equality in the workplace.

The aim of this research is to examine how the relationship between the ingroup, and outgroup (such as student-teacher relationship) impacts their perception of humanity. Additionally, it aims to analyze the moderating role of organizational dehumanization in the connection between the relationship with outgroup and humanity attribution. In essence, this study seeks to understand how interpersonal relationships within a university environment can influence a perception of the humanity of ingroup toward the outgroup and how organizational factors can moderate these perceptions.

This study contributes significantly to both theoretical understanding and practical applications within the domain of intergroup dynamics. Firstly, it addresses existing gaps in knowledge concerning infrahumanization and its interplay with organizational factors. Investigating how relationships between ingroup and outgroup members influence perceptions of humanity introduces organizational dehumanization as a crucial moderating variable, enhancing comprehension of infrahumanization dynamics. Additionally, this research offers valuable insights into intergroup dynamics within university settings by exploring the impact of group relationships on the perception of humanity. These insights hold promise for understanding biases and discrimination within social interactions (Pérez-Jorge et al., 2021). Moreover, the study underscores the importance of mitigating infrahumanization in organizational contexts to foster better work environments. Overall, this research expands theoretical knowledge while offering practical implications for addressing infrahumanization and its associated dynamics in organizational and educational settings.

Infrahumanization theory

The attribution of less humanity to other people and groups is a phenomenon of research interest (Caesens et al., 2017; Haslam et al., 2008; Haslam and Loughnan, 2014; Leyens et al., 2007). The main hypothesis of the theory of infrahumanization is based on the different attribution of primary and secondary emotions to members of an outgroup and claims that people attribute more “secondary emotions” or humanity to their group, compared to the outgroup, to which they restrict the possibility of experiencing these human emotions (Caesens et al., 2017; Haslam and Loughnan, 2014; Leyens et al., 2000; Leyens et al., 2001). This is because “secondary emotions” are a type of emotions that underlie emotional states which are particular to human beings, for example, happiness, pride, or spite. Instead, “primary emotions” are basic emotional states present in both humans and other animal species (for example, joy, fear, or pain).

Research on intergroup infrahumanization examines how people tend to attribute more humanity, particularly secondary emotions, to their ingroup while excluding these emotions from the outgroup. Key characteristics include its subtlety (Leyens et al., 2000), and dependence on the context of the outgroup, with a stronger association between secondary emotions and the ingroup in pleasant contexts compared to unpleasant ones (Leyens et al., 2001). Familiarity with a context also influences infrahumanization, as the outgroup is more likely to be infrahumanized in a familiar context (Delgado Rodríguez et al., 2012; Arriagada-Venegas et al., 2021a, 2021b; Ariño-Mateo et al., 2024). There is a significant relationship between attributing fewer secondary emotions to the outgroup and a strong identification with the ingroup (Demoulin et al., 2004). Additionally, infrahumanization occurs in minimal grouping situations, where participants strongly associate with their new ingroup and tend to infrahumanize the outgroup (Simon and Gutsell, 2020). Infrahumanization seems to imply not only a lack of recognition of the humanity of the outgroup but also an active resistance to accepting members of other groups as completely human (Cehajic et al., 2009; Cuddy et al., 2007; Leyens et al., 2000; Leyens et al., 2001; Vaes et al., 2003).

Despite a substantial body of research dedicated to comprehending the phenomenon of infrahumanization, there remains a scarcity of studies addressing the variables that either instigate or hinder infrahumanization. This study seeks to bridge this gap by pursuing two specific objectives: (1) to investigate how the relationship between the ingroup and outgroup (meaning similarity, friendship, etc. between students and teachers) affects their human perception, and (2) to analyze the moderator role of organizational dehumanization between the relationship with the outgroup and the attribution of humanity.

The humanization of the outgroup

Introducing a fictional group described in altruistic terms has been shown to increase its human profile and reduce infrahumanisation (Arriagada-Venegas et al., 2022). Similarly, introducing an outgroup in a prosocial context also influences infrahumanization, since showing the outgroup within a scenario of solidarity increases their humanity and contributes to reducing the tendency to infrahumanize them. Moreover, Davies et al. (2018) demonstrated that infrahumanization of the outgroup can be reduced by presenting an outgroup helping the ingroup after a natural disaster.

Cortes et al., (2005) have demonstrated that infrahumanization is not solely contingent upon familiarity. Participants attributed to their ingroup an equivalent number of secondary emotions as they did to themselves, despite the expectation that individuals would possess a greater understanding of their own emotions. Additionally, various outgroups of differing familiarity were tested, revealing that the most familiar outgroup experienced the highest degree of infra-humanization (Cortes et al., 2005).

The status of the outgroup has been analyzed as a factor that triggers humanization (Demoulin et al., 2004; Leyens et al., 2001). The theory of infrahumanization (Leyens et al., 2000) aligns with the classical hypothesis, grounding itself in the universal nature of ethnocentrism (Jahoda, 2013), without making distinctions between socio-economic classes. Both upper and lower-class members are anticipated to attribute more secondary emotions when describing their ingroup compared to an outgroup (Cortes et al., 2005; Leyens et al., 2001). However, in a recent study, Russo and Mosso (2019) confirmed that lower-status groups showed bias in attributions of uniquely human emotions, in favor of the higher-status outgroup, and this means that the ingroups will attribute more secondary emotions to the outgroup.

Relationship with the outgroup and infrahumanization

There are inconsistencies in the outcomes concerning this matter. Some authors (Cortes et al., 2005; Gaunt et al., 2005; Leyens et al., 2001) have demonstrated that infrahumanization occurs independently of the familiarity of the ingroup and outgroup. Similarly, Cortes et al., 2005 having contact with members of another group does not result in a lesser degree of infrahumanization. However, Hartley (1946) demonstrated that unfamiliar outgroups were often viewed negatively. Participants were asked to assess various groups based on a list of positive and negative characteristics, including three fictitious groups (e.g., Wallonians). Despite the complete unfamiliarity of these three groups, many participants responded by attributing negative characteristics to them. Moreover, Stephan & Stephan (1984) concluded an association between infrahumanization and the interdependence between groups. Furthermore, Pérez et al. (2011) affirm that outgroups that have a certain similarity with the ingroup and have relationships of friendship and knowledge are attributed more secondary emotions than other outgroups. Based on the foundation of the contact hypothesis (Allport, 1954) this study hypothesized that the closer is the relationship between professor and student the more the student humanizes them.

The moderating role of organizational dehumanization

Organizational dehumanization (OD) is characterized by employees’ experiences of being objectified and deprived of their personal subjectivity in their workplace, thereby becoming mere instruments for achieving organizational objectives (Bell & Khoury, 2011, 2016; Caesens et al., 2017). This phenomenon is associated with negative outcomes such as reduced well-being, heightened emotional exhaustion, and adverse attitudes toward the organization and work (Arriagada-Venegas et al., 2021a, 2021b; Caesens & Stinglhamber, 2019; Demoulin et al., 2021; Sarwar et al., 2021). OD arises from unfavorable working conditions, and widespread organizational policies and practices, and is intensified by ineffective leadership styles and perceptions of injustice (Bell & Khoury, 2011; Caesens et al., 2017; Clayton & Opotow, 2003). Employees in dehumanizing environments often feel replaceable, leading to decreased performance and intentions to exit the organization.

In terms of its moderating role, it is reasonable to suggest that organizational dehumanization, being a significant influence on workers’ perception of their organization, serves as a moderating factor in the relationship between the connection with the outgroup and infrahumanization. In a scenario of high organizational dehumanization, there is a decrease in workers’ identification with the organization (Haslam and Loughnan, 2014), and consequently, with the outgroup (teachers). This would allow the positive characteristics derived from a close relationship with the outgroup to be reduced, which in turn would lead to an increase in infrahumanization towards the outgroup. This phenomenon is primarily due to the fact that organizational dehumanization affects workers’ identification with their organization (Bastian & Haslam, 2011), attenuating the possible effects of a close relationship on infrahumanization. Furthermore, a dehumanizing environment diminishes the fundamental needs of workers, creating an unfavorable environment and altering workers’ behaviors (Bell & Khoury, 2011). Following this theoretical background, this study hypothesized that Organizational Dehumanization will influence the effects of the relationship between professor and student and their infrahumanization.

Methods

Participants

The sample was composed of 338 students from different courses of the Faculty of Education at the University of La Laguna selected for convenience, where 92 were men (27.2%) and 246 women (72.8%), with an average age of 22.27 years (Mean = 4.78; Min = 18; Max = 53). The study area of the participants came mainly from social and legal sciences (N = 150), health sciences (N = 102) engineering, and architecture (N = 60).

Instrument

Infrahumanization scale

The participants completed a 20-item questionnaire for the attribution of emotions to their teachers. The selection of these 20 emotions was based on a study that presents more than 100 emotional terms in different dimensions (Ariño-Mateo et al., 2022). The emotions were selected according to the score of their degree of humanity. There are ten emotions with high scores in humanity, called secondary emotions (for example serenity, empathy, hope, euphoria, and optimism), and 10 emotions with low scores in humanity, the primary emotions (Mean = 2.48, SD = 0.72) (for example affection, happiness, surprise, desire, and tenderness), t (337) = −11.38, p < 001. The way to answer is through a Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 (total disagreement) to 7 (total agreement). In this study, we selected secondary emotions to analyze the infrahumanization attributed to the teachers by the students.

Organizational dehumanization scale

The instrument used was validated and adapted in Spanish by Ariño-Mateo et al. (2022) and proposed by Caesens et al. (2017). It consists of 10 items answered in Likert format that ranges from 1 (“total disagreement”) to 7 (“total agreement”) (for example “My organization sees me as a number”, “My organization sees me as a tool for its own success”, “My organization treats me as if I were an object”). Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was 0.935 and McDonald’s omega was 0.938.

Relationship with the teacher scale

The variable “relationship with the teacher” is composed of four items, to know the relationship that the student has with the teachers. It is a Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 (total disagreement) to 7 (total agreement), for instance, “I think the professor values me”. Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was 0.821 and McDonald’s omega was 0.879.

Procedure

A list of potential study participants was compiled, and seven teachers from seven distinct faculties (Humanities and Fine Arts, Social and Legal Sciences, Health Sciences, Sciences and Engineering, and Architecture) were randomly selected to share the questionnaire with the students. To access the sample, the stratified random sampling technique was used, since the population was divided into strata (by fields of knowledge). More specifically, a simple and/or constant stratified method was used, since the same number of cases was established in each stratum (7 faculties for each field of knowledge).

Once the contact list was created, the questionnaires were sent by email. The instructions on completing the questionnaires appeared on the main page of the questionnaires, although these were also provided in writing in the email where the link to them was attached. Google Forms was used as a survey.

A period of two weeks was offered for the completion of the questionnaire, and the students took an average of 10 min for the completion of the survey. The responses obtained were automatically entered into an Excel form for subsequent analysis using version 25 of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS).

Ethics statement

Participants were informed that the personal data obtained from this study would be guarded by the researchers, guaranteeing their anonymity and confidentiality. Participants accepted voluntary participation in the study after being informed at the time of answering the questionnaire.

Analysis

The data was calculated through the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics version 24. T-test analyses were performed to test whether there were significant differences in the attribution of primary and secondary emotions.

To verify if organizational dehumanization was influencing a mediator, Hayes’ (2018) macro was used through SPSS software.

Results

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the study variables. In the first place, it is shown that there is a positive and significant correlation between the relationship with the teacher, primary emotions (ρ = 0.21, p < 0.001), and secondary emotions (ρ = 0.27, p < 0.001). Instead, there exists a negative and significant correlation with organizational dehumanization (ρ = 0.47, p < 0.001). Concerning the descriptive statistics, primary emotions, and secondary emotions have a similar average and standard deviation, in contrast to organizational dehumanization and relationship with the teacher, which present a higher mean and standard deviation.

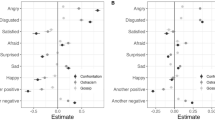

Table 2 shows the moderation model. Organizational dehumanization moderates the relationship between the teacher and secondary emotions. The results show that the organizational dehumanization variable plays a moderating role in the relationship with the teacher and secondary emotions (p < 0.001).

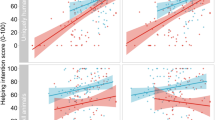

To better visualize the moderation effect, four figures are presented. Figure 1 shows the proposed model; Fig. 2 shows the results of the research model; Fig. 3 illustrates the conditional effects of the relationship with the teacher on the attribution of secondary emotions. Thus, when organizational dehumanization increases, the effect between the independent and dependent variables decreases, even when the moderating variable goes up to 5.79 (p > 0.05). Therefore, the effect of the relationship with the teachers on the attribution of secondary emotions disappears (Figs. 1, 2, and 3).

On the other hand, Fig. 4 shows the relationship between the independent variable (relationship with the teacher) and the dependent variable (attribution of secondary emotions towards teachers) in three values of organizational dehumanization: (1) average minus one standard deviation, (2) average and, (3) average plus one standard deviation. The figure shows that as organizational dehumanization increases, the relationship between the variables is lower, so the slope decreases (Fig. 4).

Discussion

The theory of infrahumanization affirms that the ingroup attributes secondary emotions (humanity) to themselves and denies this possibility to the outgroup. This theory has many studies that confirm this bias in the attribution of emotions between ingroup and outgroup and the consequences of the outgroup when it is dehumanized (Haslam and Loughnan, 2014; Leyens et al., 2001; Delgado Rodríguez et al., 2012; Arriagada-Venegas et al., 2022; Demoulin et al., 2004).

This study advances in the knowledge of the theory of infrahumanization and shows how the infrahumanization of the outgroup is influenced by the kind of relationship. As per the results of Pérez et al. (2011), the closer the relationship with the teachers, the more the ingroup humanizes the outgroup.

Additionally, this study shows the moderator role of organizational dehumanization and confirms the second hypothesis. The more the organization dehumanized the ingroup (independently if whether this perception is real or not), the more the ingroup denied secondary emotions to the outgroup, and vice versa. These results allow us to better understand the role that organizational dehumanization plays as a moderator and the infrahumanization or humanization of the outgroup and through this research, there is progress on the understanding and implications of organizational dehumanization. Results show the negative consequences of organizational dehumanization as a moderator and how the relationship with the outgroup influences their attribution of humanity.

Some limitations need to be marked. First, this research is cross-sectional, so we cannot ensure the causality of the model. In future research, we encourage experimental research studies and longitudinal studies (Sonnentag, 2003; Stadt, 1990). Second, it is necessary to take into consideration the possibility of social desirability bias in the students’ responses even though the confidentiality of the data was emphasized. Third, the gender inequality of our students, as the percentage of students enrolled in the degrees of social, legal sciences, and health sciences are grades where there is a tendency to have more females and a little number of males. Fourth, the university context represents a distinctive organizational environment, particularly when contrasted with studies on organizational dehumanization conducted in private companies.

For future research it will be of great interest to analyze deeper within this new research line and evaluate if all teachers are considered part of a high-status group, and what factors are associated with this high-status perception. Also, it would be interesting to analyze the outcomes of humanizing or dehumanizing the teachers regarding performance, assistance to class, motivation to the topic, etc. from the student’s perspective and burnout or stress from the teachers.

In the same way, it would be very interesting to extrapolate this research to the organizations and to know what characteristics of the relationship between ingroup and outgroup (transparency in relationships, self-awareness, balanced processing, and internalized morality) are associated with the attribution of secondary emotions. It is also relevant to advance on the factors that cause the students to be perceived as dehumanized by the organization.

Conclusions

This study is a pioneer in investigating organizational dehumanization in the university context. Organizational dehumanization was found to have a moderator role in this relationship and consequently, the students who saw themselves as less dehumanized by their organization attributed more humanity to the teachers.

These findings highlight the role that organizational dehumanization can play in an educational context, within students and teachers, and organizational context, to employees and leaders, and give us the evidence to continue advancing the knowledge of organizational dehumanization, and how students and employees can change the perception of being dehumanized by their teacher, leaders and organizations, and the consequences of the dehumanization.

The funders did not participate in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

Data will be provided upon request to the correspondence author.

References

Allport GW (1954) The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley

Ariño-Mateo E, Venegas MA, Mora-Luis C, Pérez-Jorge D (2024) The level of conscientiousness trait and technostress: a moderated mediation model. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02766-3

Ariño-Mateo E, Ramírez-Vielma R, Arriagada-Venegas M, Nazar-Carter G, Pérez-Jorge D (2022) Validation of the organizational dehumanization scale in Spanish-speaking contexts. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(8):4805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084805

Arriagada-Venegas M, Ariño-Mateo E, Ramírez-Vielma R, Nazar-Carter G, Pérez-Jorge D (2022) Authentic leadership and its relationship with job satisfaction: the mediator role of organizational dehumanization. Europe’s J Psychol 18(4):450. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.6125

Arriagada-Venegas MA, Ramírez R, Ariño-Mateo EA (2021a) The moderating role of organizational dehumanization in the relationship between authentic leadership and organizational citizenship behaviors. UCJC Bus Soc Rev 18(1):90–127. https://doi.org/10.3232/UBR.2021.V18.N1.03

Arriagada-Venegas M, Ramírez-Vielma R, Ariño-Mateo E (2021b) El rol moderador de la deshumanización organizacional en la relación entre el liderazgo auténtico y los comportamientos ciudadanos organizacionales. UCJC Bus Soc Rev (Former Known. Universia Bus Rev) 18(1):90–127. https://doi.org/10.3232/UBR.2021.V18.N1.03

Bastian B, Haslam N (2011) Experiencing dehumanization: Cognitive and emotional effects of everyday dehumanization. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 33(4):295–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2011.614132

Bell CM, Khoury C (2016) Organizational powerlessness, dehumanization, and gendered effects of procedural justice. J Manag Psychol 31(2):570–585. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-09-2014-0267

Bell CM, Khoury C (2011) Dehumanization, deindividuation, anomie and organizational justice. In Gilliland S, Steiner D, & Skarlicki D (eds) Emerging Perspectives on Organizational Justice and Ethics, Research in Social Issues in Management. Information Age Publishing, pp 169–200

Caesens G, Stinglhamber F (2019) The relationship between organizational dehumanization and outcomes: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. J Occup Environ Med 61(9):699–703. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001638

Caesens G, Stinglhamber F, Demoulin S et al. (2017) Perceived organizational support and employees’ well-being: the mediating role of organizational dehumanization. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 26(4):527–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2017.1319817

Castano E, Giner-Sorolla R (2006) Not quite human: Infrahumanization in response to collective responsibility for intergroup killing. J Personal Soc Psychol 90(5):804–818. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.804

Čehajić S, Brown R, González R (2009) What do I care? Perceived ingroup responsibility and dehumanization as predictors of empathy felt for the victim group. Group Process Intergroup Relat 12(6):715–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430209347727

Cheung F (2023) The relationship between organizational dehumanization and family functioning. Occup Health Sci 7:793–803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-023-00157-9

Clayton S, Opotow S (2003) Justice and identity: Changing perspectives on what is fair. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 7:298–310. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0704_03

Cortes BP, Demoulin S, Rodriguez RT, Rodriguez AP, Leyens JP (2005) Infrahumanization or familiarity? Attribution of uniquely human emotions to the self, the ingroup, and the outgroup. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 31(2):243–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271421

Cuddy AJC, Rock MS, Norton MI (2007) Aid in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: inferences of secondary emotions and intergroup helping. Group Process Intergroup Relat 10(1):107–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430207071344

Davies T, Yogeeswaran K, Verkuyten M et al. (2018) From humanitarian aid to humanization: when outgroup, but not ingroup, helping increases humanization. PLoS ONE 13(11):e0207343. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207343

Delgado Rodríguez N, Rodríguez-Pérez A, Vaes J, Rodríguez VB, Leyens JP (2012) Contextual variations of infrahumanization: the role of physical context and territoriality. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 34(5):456–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.712020

Demoulin S, Leyens JP, Paladino MP et al. (2004) Dimensions of “uniquely” and “non‐uniquely” human emotions. Cognition Emot 18(1):71–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930244000444

Demoulin S, Nguyen N, Chevallereau T, Fontesse S, Bastart J, Stinglhamber F, Maurage P (2021) Examining the role of fundamental psychological needs in the development of metadehumanization: A multi‐population approach. Br J Soc Psychol 60(1):196–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12380

Gaunt R, Sindic D, Leyens JP (2005) Intergroup relations in soccer finals: people’s forecasts of the duration of emotional reactions of in-group and out-group soccer fans. J Soc Psychol 145(2):117–126. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.145.2.117-126

Hartley EL (1946) Problems in prejudice. King’s Crown Press

Haslam N, Loughnan S (2014) Dehumanization and infrahumanization. Annu Rev Psychol 65(1):399–423. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115045

Haslam N, Kashima Y, Loughnan S et al. (2008) Subhuman, inhuman, and superhuman: Contrasting humans with nonhumans in three cultures. Soc Cogn 26(2):248–258. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2008.26.2.248

Hayes AF (2018) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis, second edition: a regression-based approach (2nd edn.). Guilford Publications

Jahoda G (2013) An anthropological history of dehumanization from late-18th to mid-20th centuries. In Bain P, Vaes J & Leyens J (eds) Humanness and dehumanization. Routledge, pp 13–33

Leyens JP, Paladino PM, Rodriguez-Torres R et al. (2000) The emotional side of prejudice: the attribution of secondary emotions to ingroups and outgroups. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 4(2):186–197. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_06

Leyens JP, Rodriguez-Pérez A, Rodriguez-Torres R et al. (2001) Psychological essentialism and the differential attribution of uniquely human emotions to ingroups and outgroups. Eur J Soc Psychol 31(4):395–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.50

Leyens J-P, Demoulin S, Vaes J et al. (2007) Infra-humanization: The wall of group differences. Soc Issues Policy Rev 1(1):139–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2007.00006.x

Pérez AR, Rodríguez ND, Rodríguez VB et al. (2011) La infrahumanización de exogrupos en el mundo. de Psicolía 27(3):679–687. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.27.3.148401

Pérez-Jorge D, Ariño-Mateo E, González-Contreras AI, del Carmen Rodríguez-Jiménez M (2021) Evaluation of diversity programs in higher education training contexts in Spain. Educ Sci 11(5):226. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050226

Rodríguez-Pérez A, Delgado-Rodríguez N, Betancor-Rodríguez V, Leyens J. P, Vaes J (2011) Infra-humanization of outgroups throughout the world. The role of similarity, intergroup friendship, knowledge of the outgroup, and status. Anales de Psicología 27(3):679–687

Rudman LA, Mescher K (2012) Of animals and objects: Men’s implicit dehumanization of women and likelihood of sexual aggression. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 38(6):734–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212436401

Russo S, Mosso CO (2019) Infrahumanization and Socio-structural variables: The role of legitimacy, ingroup identification, and system justification beliefs. Soc Justice Res 32(1):55–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-018-0321-x

Sarwar A, Khan J, Muhammad L, Mubarak N, Jaafar M (2021) Relationship between organisational dehumanization and nurses’ deviant behaviours: A moderated mediation model. J Nurs Manag 29(5):1036–1045. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13241

Simon JC, Gutsell JN (2020) Effects of minimal grouping on implicit prejudice, infrahumanization, and neural processing despite orthogonal social categorizations. Group Process Intergroup Relat 23(3):323–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430219837348

Sonnentag S (2003) Psychological management of individual performance. Wiley

Stadt RW (1990) Productivity in organizations: new perspectives from industrial and organizational psychology. In: Campbell JP (ed) New perspectives from industrial and organizational psychology. Jossey-Bass, pp 31–95

Stephan WG, Stephan CW (1984) The role of ignorance in intergroup relations. In Miller N & Brewer M (eds) Groups in contact: The psychology of desegregation. Academic Press, pp 229–255

Vaes J, Paladino MP, Castelli L et al. (2003) On the behavioral consequences of infrahumanization: the implicit role of uniquely human emotions in intergroup relations. J Personal Soc Psychol 85(6):1016–1034. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.6.1016

Acknowledgements

This research has been sponsored by “Conselleria de Educación, Universidades y Empleo de la Generalitat Valenciana”. Project reference: (CDEIGENT/2021/003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: EA-M and DP-J. Data curation: EA-M, MA-V, and DP-J. Formal analysis: EA-M, IA-R, and DP-J. Investigation: EA-M and DP-J. Methodology: EA-M, MA-V, and DP-J. Project administration: EA-M, DP-J, and IA-R. Resources: EA-M, MA-V, and DP-J. Supervision: EA-M., DP-J, and IA-R. Validation: EA-M, MA-V, and DP-J. Writing—original draft: EA-M, MA-V, and DP-J. Writing—review & editing: EA-M, DP-J, and IA-R.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study received the approval of the Ethics Committee of the European Scientific Institute (ESI), as indicated by the reference number Protocol ESI 2020/005 (Approved on 2021-11-16). In adherence to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (1964-2013), all participants were thoroughly informed about their involvement in the development of the questionnaire and their rights. Informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to their participation in the study. To ensure privacy and confidentiality, all statistical analyses were performed on anonymized data.

Informed consent

The researchers requested and received the consent of the participants regarding their participation in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ariño-Mateo, E., Arriagada-Venegas, M., Alonso-Rodríguez, I. et al. Your humanity depends on mine: the role of organizational dehumanization in the context of university studies. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 418 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02880-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02880-2