Abstract

Studies on the pandemic suggest that COVID is related to many facets of adolescent development (i.e., Golberstein et al., JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 819–820, 2020). Although the full consequences of COVID on social, economic, and health outcomes are not yet fully known, the impact is predicted to be long-lasting (Prime et al., American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643, 2020). This paper is a systematic review that focuses on the COVID pandemic’s change in adolescents’ relationships with their siblings, peers, and romantic partners, as well as the role of these relationships in helping adolescents navigate through the uncertainties of this period. Studies from several different countries were selected using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (Page et al., International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906, 2021). Overall, the findings are mixed, with some results showing no change or relationship between COVID and each of the adolescent relationships examined, while other results indicated significant positive and/or negative changes or relationships. We hope our review of this growing body of literature will provide guidance and recommendations for researchers moving forward with specific studies examining the change in adolescents’ relationships with siblings, peers, and romantic partners- and the roles of these relationships during the COVID pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peer relationships, as well as romantic relationships, become more salient during adolescence as adolescents navigate to establish and maintain healthy relations with peers. Until recently, much of the research examining peer relations among adolescents focused on negative outcomes, such as involvement with deviant peers, substance abuse, poor school performance, etc. However, in the past decade or so, researchers have also focused on the many potential positive outcomes of peer influence on adolescents (Laursen & Veenstra, 2021). Similarly, sibling relationships serve as the first peer relationships for many children and adolescents, and sibling relationships can serve as important sources of support (Conger et al., 2020; McHale et al., 2012) as well as a negative influence on adolescent development (Jensen et al., 2018; Whiteman et al., 2016). This systematic review delves into the repercussions of the COVID pandemic (beyond the disease itself, such as social distancing and other consequences because of the pandemic) on the dynamics of adolescent relationships with siblings, peers, and romantic partners. In particular, this study will identify the changes in adolescents’ relationships with their siblings, peers, and romantic partners. Additionally, the paper explores how these relationships play a role in aiding adolescents as they navigate the uncertainties associated with this challenging period.

Sibling relationships

While parents are considered primary socialization agents earlier in childhood (Grusec, 2002; Handel 2011), studies have shown that siblings also play key roles in adolescents’ well-being (e.g., Kramer et al., 2019), especially for girls (Oliva & Arranz, 2005). Studies on sibling relationships have established the roles of siblings as companions (Orsmond & Long, 2021), confidantes (Killoren & Roach, 2014; Killoren et al., 2019), and role models (Whiteman et al., 2014). Siblings are also those whom one learns social skills (Mancillas, 2011) and to whom one turns for social support (Tucker et al., 2001).

Sibling relationships can serve as an important source of support during adolescence (Gass et al., 2007). More specifically, siblings may often share interests that facilitate interactions, especially siblings relatively close in age. Earlier in childhood, power discrepancies between the older and younger siblings are pronounced due to children’s rapid physical and cognitive development, making their differences appear to be dramatic (Lindell & Campione-Barr, 2017). As they get older, however, the developmental gap between siblings may get closer, providing opportunities for sibling relationships to become more egalitarian from adolescence to adulthood (Buhl, 2009; Tsai et al., 2013). Previous studies have shown that a close, positive sibling relationship can be a protective factor against family-wide stressors and stressful life events (e.g., Waite et al., 2011) and internalizing and externalizing symptoms (e.g., Buist et al., 2013). On the other hand, the pandemic may also increase sibling conflicts. For example, previous research (e.g., Rittenour et al., 2007) has established that siblings who have a high level of contact with each other share greater intimacy. This is also known as co-rumination, a social-support seeking behavior common in adolescence, characterized by rehashing and speculating problems and mutual encouragement of problem talk (Rose, 2002), which are usually found in peer relationships. It is possible that with a lack of contact with peers, adolescents who turn to their siblings to connect may become more intimate, however, they may also become conflictual. For example, Toseeb (2022) suggests that the rates of sibling conflicts were high during the COVID lockdown, although their sample only focuses on children with special educational needs and disabilities in the United Kingdom. Toseeb’s 2022 longitudinal study was also further supported by the finding of a decrease in sibling conflicts once the schools had fully re-opened for face-to-face classes. Conflict and negative relationships with siblings were found to affect adolescent adjustments (Dirks et al., 2015), therefore, more studies are needed to understand the complexities of sibling relationships.

Peer relationships

Studies have established that peers play a prominent role during adolescence in establishing independence from their parents (Collins & Steinberg, 2008). During the lockdown periods, most adolescents were attending school virtually via the Internet and thus were not able to physically meet and interact with their close friends or general peers (Loades et al., 2020; Morrissette, 2021). Moreover, most lockdown guidelines restricted social interaction in person, and most parents and local authorities enforced these guidelines (Mervosh et al., 2020). Several studies report that adolescents have overwhelmingly indicated that their number one concern during the COVID lockdown period was being unable to see their friends (Magson et al., 2021). Typically, peers serve as sources of support for adolescents during times of stress (Laursen & Veenstra, 2021). While preliminary evidence suggests that peers still exerted some positive influence on adolescents, evidence also suggests that the structural constraints placed on peer relationships during the COVID lockdown periods (e.g., stay-at-home orders, school and event closures, etc.) also had a negative influence on these important relationships (e.g., Magis-Weinberg et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2022).

The result was that most adolescents were restricted to interacting with their peers only via texting, telephone calls, video chats, and various sources of social media (Magis-Weinberg et al., 2021). Simultaneously, most adolescents were now restricted to their family’s home and face-to-face interactions with their parents and siblings. Although this opened the door for increased interaction with siblings and parents, peer relationships were structured differently and thus might have had different impacts on adolescent outcomes (e.g., Magis-Weinberg et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2022).

Romantic relationships

Adolescent romantic relationships have gained more attention as an important predictor of a foundation for future relationships (Collins, 2003). While studies found positive outcomes associated with adolescent romantic relationships (Shulman, 2003), there are also negative outcomes (Davies & Windle, 2000; Price et al., 2016; Van Dulmen et al., 2008). By late adolescence, most adolescents are reported to have had at least one romantic relationship (Carver et al., 2003), and the interdependencies with romantic partners become more apparent (Collins, 2003). The period of adolescence often involves the onset of dating as this interaction serves many developmental functions for them, such as intimacy, companionship, experimentation with gender-role behavior, sexual activity (Grover et al., 2007), and security (Van Dulmen et al., 2008). Similar to peer relationships, the time spent with romantic partners increased in adolescence (Reis et al., 1993), and romantic relationships were one of the types of relationships that were affected the most during the COVID lockdown (Dotson et al., 2022). On the other hand, relational maintenance, that is, preserving a relationship's existence (Duck, 1988), has been done in many ways. For example, Licoppe (2004) introduced the notion of “connected presence,” in which the capacity to connect with others has resulted in an ongoing practice of connecting to others in various manners. Prior to COVID, long-distance relationships, for example, used technology as a way to maintain romantic relationships (Valentine, 2006). COVID lockdown forces adolescents to utilize technology as a way to maintain their romantic relationships. However, Dotson et al. (2022) claimed that physical distancing as a result of preventing COVID infection from spreading also creates emotional distancing. They also claimed that it was harder to maintain affective connections through technology and within the isolating context of shelter-in-place. Although using technology is nothing new for this generation, it will be important to find out whether the lockdown peri-COVID affected their romantic relationships.

Current study

The purpose of the current study is to conduct a systematic review of literature that has examined how COVID has changed adolescents’ relationships with their siblings, peers, and romantic partners throughout the pandemic (pre- and post-) as well as the role of these relationships during COVID (i.e., how do each of these adolescent relationships relate to various adolescent/family outcomes). The systematic review on this topic can help provide an understanding of the complexities of relationships during adolescence with the additional stress of COVID. Since adolescents’ relationships are closely tied to their well-being, it is hoped that this will help inform future research, policy decisions, and healthcare providers and practitioners to develop more targeted interventions.

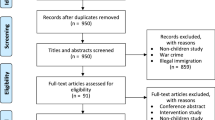

First stage: Search strategies

A systematic search was conducted by authors on Academic Search Complete and APA PsychInfo via Ebsco Host from March 2020 until January 29th, 2023. The keywords used are COVID + Adolescent + specific relationships (i.e., sibling relationships, peer relationships, romantic relationships). Each study selected must also be an individual study with original data, and the automation tool automatically filtered the duplicates and non-peer review articles. By the end of the first stage, nine articles on sibling relationships, thirty articles on peer relationships, and nine articles on romantic relationship studies were identified.

Second stage: Eligibility and inclusion criteria and screening procedures

The articles identified were screened as abstracts and summarized by the first author (reviewer 1). A list of criteria was considered: 1. must be an original academic study with data (e.g., not opinion pieces, or literature review, etc.); 2. must be published in English; 3. studies must be conducted particularly on or about adolescents (age 10–20). After excluding the studies that did not meet these inclusion criteria, the articles were carefully assessed by both authors independently (reviewers 1 and 2) to be included in the next stage. At this point, four articles were removed from the sibling group, seven were excluded from the peer group, and three papers were excluded from the romantic relationship group to conform to the aforementioned criteria (therefore nSibling = 5; nPeers = 23; and nRomantic = 6). Articles were then carefully and thoroughly read, and results were compiled. Then, the studies were screened out based on these additional exclusion criteria: 1) not measuring siblings/peers and/or romantic partner-adolescent relationships; and 2) not specifically studying adolescents during the lockdown period (also including post-COVID studies that analyzed the aftermath of the lockdown period). At the end of the second stage, two were removed from the sibling group, another seven were excluded from the peer group, and none were removed from the romantic relationship group. A total of three papers that measure sibling-adolescent relationships, sixteen peer-adolescent relationship papers, and six papers on adolescent romantic relationship studies were included in the final stage.

Final stage: Final screening procedure and analysis

Articles were carefully and thoroughly read, and the measures for each relationship were identified. At this stage, we chose these inclusion criteria: 1) assess the change in adolescent relationships with siblings/peers/romantic partners from pre-COVID to post-COVID lockdown and/or 2) assess the role of these relationships (sibling, peer, romantic partner) in regard to various outcomes (e.g., mental health, academic achievement) during the COVID lockdown. The articles in the final list (nSiblings = 3; nPeers = 8; nRomantic = 6) were then thoroughly reviewed and reported in this study (refer to Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Results

Sibling relationships

Three studies were selected to be discussed in the current study, with all of them using longitudinal designs and conducted among US samples. All of the studies examined the changes in sibling-adolescent relationships (Campione-Barr et al., 2021; Cassinat et al., 2021; Gadassi Polack et al., 2021), while two papers specifically examined the role of sibling relationships during COVID (Campione-Barr et al., 2021; Gadassi Polack et al., 2021). More specifically, Campione-Barr et al. (2021) examined the role of sibling relationships that affect depressive symptoms, anxiety, and problem behavior, while Gadassi Polack et al. (2021) studied the role of sibling relationships that affect depressive symptoms.

Of the three studies discussed in this current study, only one study (Campione-Barr et al., 2021) assessed the quality of sibling relationships directly using the Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI) (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985), while the others used one or more components or indicators of the quality of sibling relationships. The components or indicators used to assess sibling relationships included intimacy, disclosure, conflict (Cassinat et al., 2021), and interpersonal reactions using diary input (Gadassi Polack et al., 2021).

Campione-Barr et al. (2021) reported that the median age of the older siblings at T2 (the time when they collected particularly studying on COVID) from their sample was 17.4, and their younger siblings’ median age was 14.9. Cassinat et al. (2021) reported that the age at Time 1 for the older siblings of their sample is from grades 8–10 (Mage = 15.67); while the age at Time 1 for the younger siblings is from grades 5–9 (Mage = 13.14). Finally, Gadassi Polack et al. (2021) sample includes older siblings aged from 11–15 at baseline (13–17 during T2 peri-COVID) while the younger siblings were 8–12 at the baseline (9–12 during T2 peri-COVID).

All of the studies T1 were pre-COVID (Campione-Barr et al. T1 = June ‘17-Dec ‘18); Cassinat et al. T1 = March ‘19-March ‘20; Gadassi Polack et al. T1 = 2019). Time 2 for each study are peri-COVID (Campione-Barr et al. T2 = June ‘20-July ‘20); Cassinat et al. T2 = May ‘20-June ‘20; Gadassi Polack et al. T2 = March ‘20). It is also important to note that although Campione-Barr and colleagues used longitudinal data, they only measured the relationship quality in T2 (peri-pandemic).

Changes in adolescent-sibling relationships during COVID lockdown

Campione-Barr et al. (2021) used a cross-sectional finding within their longitudinal data in which they did not assess change in sibling relationships across time. In this study, they found that COVID-related stress was not significantly related to positive or negative sibling relationships. However, they found that older adolescents in their study reported less negative relationship quality with siblings.

The two studies that examined changes between multiple points in time were Cassinat et al. (2021) and Gadassi Polack et al. (2021). Both of these studies reported that the main effect for overall mean level change in adolescents’ reports of sibling intimacy across time (from pre-COVID to peri-COVID) was not significant. However, Cassinat et al. (2021) found that family chaos increased from pre-COVID to peri-COVID and that family chaos was significantly related to increased sibling conflict and decreases in sibling intimacy as well as sibling disclosure during the COVID lockdown. On the other hand, Gadassi Polack et al. (2021) found some significant effects for the age of adolescents (with older siblings reporting a significant increase in positive interactions with siblings).

Additionally, Cassinat et al. (2021) found a few key variables that affect the pattern of change- gender and birth order. Relationship quality with siblings declined significantly for boys (when comparing pre- and peri-COVID) as compared to girls. The next indicator was self-disclosure. It was reported that sibling disclosure for boys decreases when comparing their relationship before and during the pandemic, as compared to girls over time. Relatedly, they reported decreases in self-disclosure among mixed-gender sibling dyads as compared to same-gender dyads as well. Cassinat et al. (2021) also found a significant association with siblings' age spacing, in which sibling disclosure decreases over time for siblings who have a bigger age gap compared to those who are closer in age. Finally, the last indicator was sibling conflicts. Similar to sibling intimacy, although the effect for mean level change across time was not significant, the pattern of change was associated with key variables such as birth order and adolescent age. Younger siblings reported declines in conflict when comparing pre- and peri-COVID with older siblings as compared to older siblings' reports. As for the adolescent’s age, older siblings reported less change in conflict with their siblings. In all three indicators, Cassinat et al. (2021) suggested that sibling intimacy and disclosure decrease, while conflict increases when family chaos is high.

Gadassi Polack et al. (2021) also reported that in three-way interaction (Time*Context*Age), they found that positive relationships increase with siblings among their older age sample (age 13 and older). They also reported that when they conducted paired-sample t-tests measuring Time* Context, all their participants (who were 12 years of age or younger, as well as 13 and older) reported the highest frequency of negative interactions with siblings compared to other types of relationships (mother, father, and friends). The three-way ANOVA interaction (Time*Context*Age), however, did not reveal a significant effect.

Role of adolescent-sibling relationships during COVID

Although research in the past suggests that close and positive sibling relationships have been found to be a protective factor against internalizing and externalizing symptoms (e.g., Buist et al., 2013), Campione-Barr et al. (2021) reported using their correlational data on relationship quality between siblings to show no direct significant relationships between sibling relationships and the outcomes tested (anxiety, depression, and problem behavior). However, the authors did find some significant interactions, including that close relationships with siblings were associated with greater problem behavior when COVID-related stress is high. In other words, stress related to COVID influenced the positive relationship between siblings to have negative outcomes. Negative sibling relationships (only if combined with lower COVID stress) are also associated with higher anxiety (Campione-Barr et al., 2021).

On the other hand, Gadassi Polack et al. (2021) reported that positive and negative interactions between adolescents with family members, including siblings, significantly predicted depressive symptoms when comparing T1 and T2 (pre- and peri-COVID).

Peer-relationships

Eight studies from the literature were selected for examination in the current study, with five being longitudinal and three cross-sectional studies. Of the eight studies selected, two were conducted in the United States, and one each from Italy, Canada, China, Peru, Australia, and the Netherlands.

There are four studies that used longitudinal data to measure the changes during multiple time points (Gadassi Polack et al., 2021; Hutchinson et al., 2021; Magson et al., 2021; and Stevens et al., 2022). Four other studies (Laurier et al., 2021; Magis-Weinberg et al., 2021; Trombetta et al., 2022; and Zhu et al., 2022) used data measured at one point (reflecting the time of lockdown).

As for the studies that examined longitudinal data, Gadassi Polack et al. (2021) compared the changes in peer relationships in T2 peri-COVID (March 2020-June 2020) to their baseline data from pre-COVID (Jan 2019-Sept 2019). Hutchinson et al. (2021) studied the role of peer relationships by comparing their data on suicidal ideation at T2 peri-COVID (April–May 2020) to peer connectedness during T1 early peri-COVID (March 2020). Magson et al. (2021) examined change in mental health when comparing T1 pre-COVID (2019) to T2 peri-COVID (May 2020). Finally, Stevens and colleagues (2022) studied mental health (measured by multiple factors, peer relationship problems were one of the indicators) using three timelines T1 pre-COVID (Oct-Jan 2020), T2 peri-COVID (May 2020-June 2020), and T3 peri-COVID (Nov 2020-Jan 2021). It is important to note that there was a second lockdown in the Netherlands from December 2020 to March 2021, which means that the study’s T3 is during the second lockdown.

Although Magis-Weinberg et al. (2021) collected data on multiple points (all peri-COVID) T1 (week 6 of lockdown), T2 (week 7), T3 (week 8), and T4 (week 11), we are specifically interested in one of their measures (perceived social support by peers), and it was measured only on T3. A Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support was conducted on week 8 into lockdown; hence, we treated these findings as a correlational study, particularly related to changes in peer relationships during the COVID pandemic.

Four of the studies examined the changes in adolescent-peer relationships (Gadassi Polack et al., 2021; Stevens et al., 2022; Trombetta et al., 2022; and Zhu et al., 2022) from pre-COVID to post-COVID lockdown; while six examined the role of peer relationships during COVID (Gadassi Polack et al., 2021; Hutchinson et al., 2021; Laurier et al., 2021; Magis-Weinberg et al., 2021; Magson et al., 2021; and Zhu et al., 2022). More specifically, the studies examined the role of peer relationships with positive/negative online experiences, loneliness, and screen time (Magis-Weinberg et al., 2021), mental health difficulties, and peer victimization (Zhu et al., 2022); suicidal ideation (Hutchinson et al., 2021), depressive symptoms (Gadassi Polack et al., 2021; Laurier et al., 2021), spillover relationship quality with others such as parents and siblings (Gadassi Polack et al., 2021), anxiety (Laurier et al., 2021; Magson et al., 2021), life satisfaction (Magson et al., 2021), mental health (Stevens et al., 2022), and psychological distress (measured by total distress, irritability, and cognitive problems) (Laurier et al., 2021).

Changes in adolescent-peer relationships during COVID lockdown

Four studies (Gadassi Polack et al., 2021; Stevens et al., 2022; Trombetta et al., 2022; and Zhu et al., 2022) examined the changes in adolescent-peer relationships during the COVID pandemic, and the findings are mixed.

Two studies using correlational data are Trombetta et al. (2022) and Zhu et al. (2022). Trombetta et al. (2022) found a higher score on positive peer relationships, specifically for adolescents with somatic symptom disorder (as compared to adolescents hospitalized without somatic symptom disorder). This is also similar to Zhu et al. (2022) study, which found only girls reported higher scores on positive peer relationships. Both Trombetta and Zhu’s studies used correlational data.

Gadassi Polack et al. (2021) used a longitudinal study and found that negative interactions for both groups (12 and under, and 13 and older) decreased when comparing T1 and T2. They also made an important note that contrary to what is considered the norm in adolescents’ development trajectory, the family unit’s importance increased during the lockdown, while peer importance went down. Gadassi Polack et al. (2021) also found that the younger participants (12 and under) reported a decrease in the number of positive interactions with their peers, which was higher when comparing T2 and T1. Similarly, Stevens et al. (2022) reported that peer relationship problems were higher during the lockdown. More importantly, they reported that the problems were more pronounced in T2-T1 than in T3-T1.

Role of adolescent-peer relationships During COVID

The role of adolescent-peer relationships was found to have mixed results in both cross-sectional and longitudinal data.

Laurier et al. (2021), in their correlational data (which is a part of a longitudinal study) suggest that greater attachment security to peers was associated with fewer symptoms of total distress, anxiety, and irritability (although not significant for depression). On the other hand, Zhu et al. (2022) found that peer relations have no significant effects on mental health difficulties. The quality of peer relationships also was not a significant moderator to buffer the relationship between peer victimization and mental health in Zhu et al. (2022) cross-sectional sample.

The longitudinal studies also produced mixed results, similar to the cross-sectional studies. In several studies, positive peer relations were found to protect adolescents during this stressful time. For example, peer connectedness served as a buffer against negative outcomes, including a lower likelihood of suicidal ideation (Hutchinson et al., 2021). Specifically, anticipated positive peer feedback was associated with greater neural activation (particularly significant for the caudate, putamen, and anterior insula). These neural activations were significantly associated with the reduced odds of reporting suicidal ideation at Time 2 (peri-COVID). Caudate and anterior insula (but not putamen) to anticipated positive peer feedback remained significantly associated with reducing the odds of reporting suicidal ideation at Time 2, even after controlling for depressive symptoms at the baseline (early peri-COVID). Another longitudinal study which assessed multiple timelines during lockdown (T1: week 6 of lockdown), T2 (week 7), T3 week 8, and T4 week 11, Magis-Weinberg et al. (2021) suggest that friend support was strongly associated with positive online experiences and screen time.

On the other hand, another noted that there are no significant effects of peer relations on depressive symptoms, anxiety, and changes in life satisfaction (Magson et al., 2021). It was also found that the number of interactions with friends, whether positive or negative, did not significantly relate to increases in depressive symptoms (Gadassi Polack et al., 2021) pre- and peri-COVID.

Romantic relationships

Six studies were selected to be discussed in the current study, with three of them using longitudinal designs and three cross-sectional designs. Two of the studies were conducted in the US (Wright & Wachs, 2021; Yarger et al., 2021), while one each was from Kenya, Italy, Spain, and Canada. Five of these studies examined the relationship between COVID and adolescent romantic relationships or the changes in adolescent romantic relationships (Dias & Ellis, 2022; Karp et al., 2021; Pedrini et al., 2022; Wright & Wachs, 2021; Yarger et al., 2021).

Of the six studies, three specifically examined the role of romantic relationships during COVID (Dias & Ellis, 2022; Tamarit et al., 2020; Wright & Wachs, 2021). That is, only three studies examined relationships between adolescent’s romantic relationships and other outcomes during COVID.

As for the studies that examined longitudinal data, Pedrini et al. (2022) examined changes in perceived stress in romantic relationships from Time 1, pre-COVID (November, 2019—January, 2020) to Time 2, post-COVID (April—May, 2021). Dias and Ellis (2022) examined the relationship between COVID-19-related stress at T1 (January, 2021—during lockdown, schools reopened from February 16—April 12, 2021) to romantic relationship quality of adolescents at T2 (June, 2021, peri-covid, post-lockdown), approximately six months later.

Changes in adolescent romantic relationships during COVID lockdown

Overall, there were mixed findings regarding how COVID has significantly related to adolescents’ romantic relationships both across time and cross-sectionally. We will present the cross-sectional findings first (including cross-sectional findings examined within longitudinally designed studies) and then compare these to the longitudinal findings where the possibility of identifying causal relationships exists.

The cross-sectional findings include retrospective questions where researchers asked participants to assess their romantic relationships since or during covid, especially related to perceived differences/changes pre-COVID to during COVID or COVID lockdown or post-COVID lockdown. Researchers reported that for 25% of their sample, COVID had no impact on the quality of adolescent romantic relationships (Dias & Ellis, 2022). Studies also reported that around 23% of participants reported that their romantic relationships decreased in closeness during COVID (Dias & Ellis, 2022; Karp et al., 2021). On the other hand, Dias and Ellis (2022) found that over 40% of participants reported that their romantic relationships became closer during COVID, while Karp et al. (2021) found that only 22% of their participants reported that their romantic relationships increased in quality during COVID.

Wright and Wachs (2021) study found a significant correlation within the Time 2 data, where self-isolation at Time 2 was negatively associated with romantic relationship quality at Time 2 (as well as in Time 1), suggesting that self-isolation affected their relationship negatively. This was also supported by cross-sectional findings from another study where participants reported that being physically apart from their partners was significantly and negatively correlated with their romantic relationships (Yarger et al., 2021). Yarger et al. (2021) reported that retrospective questions assessing the percentage of youth who spent time daily with their romantic partner declined from 13% before COVID to 9% during COVID lockdown; similarly, retrospective questions assessing the percentage of youth who spent time weekly with their romantic partner declined from 13% before COVID to 8% during COVID lockdown. Yarger et al. (2021) also reported reduced sexual activity during the COVID pandemic, which isn’t surprising given the restrictions on traveling and face-to-face meetings/interactions. Given that the study conducted by Yarger et al. (2021) examined a group of adolescents as well as a group of young adults, it’s important to note that they found that adolescents are more likely to be physically distanced from their partners as compared to young adults. This finding makes sense logically because parents of teens might be more likely to enforce the lockdown rules than parents of young adults; and/or it might also be due to teens likely having less access to transportation than young adults.

Other interesting cross-sectional results include the relationship to income/economics, time spent together, and communication between romantic partners. Karp et al. (2021) found that partial or complete household income loss was associated with a decrease in relationship quality as compared to those who were not economically impacted by COVID. Similarly, adolescents from wealthier families reported improvement in relationship quality. Karp et al. (2021) also reported that the strongest cross-sectional predictor of changes in relationship quality was the amount of time spent with partners, in which those who spent less time with partners were more likely to report relationship change (i.e., retrospectively). Those who spent more time with partners were reported to be more likely to experience mixed-quality dynamics based on the discordant changes in emotional support and tension. Yarger et al. (2021) suggest that although adolescents retrospectively reported an increased amount of time communicating with their partner via FaceTime, texts, and calls, they were less likely to report more time sexting compared to the young adult group.

Regarding longitudinal findings, one found positive relationships (Pedrini et al., 2022), and one found no significant relationship (Dias & Ellis, 2022). More specifically, Pedrini et al. (2022) reported that perceived stress in romantic relationships decreased from Time 1 (pre-COVID) to Time 2 (peri-COVID). Dias and Ellis (2022) found that COVID-19-related stress at time one (peri-COVID, peri-lockdown) was not significantly related to romantic relationship quality of adolescents at time two (peri-COVID, post-lockdown), approximately six months later.

Role of romantic relationships during COVID

Three of the six studies selected focused on examining the role of adolescent’s romantic relationships during COVID. Focusing on the cross-sectional findings first, Tamarit et al. (2020) conducted a cross-sectional study peri-COVID after the lockdown and reported that adolescents involved in romantic relationships were less likely to show symptoms of depression and stress, although there was not a significant relationship between romantic relationships and anxiety symptoms. Wright and Wachs (2021) found that technology used for romantic relationship maintenance at T2, positively correlated with adolescent’s romantic relationship quality at T2. Even for couples who rated high scores in self-isolation, the technology used for relationship maintenance seems to help weaken the negative link between self-isolation and romantic relationship quality. Those who reported high scores in self-isolation and lower levels of technology use for romantic relationship maintenance also reported less romantic relationship quality. Lastly, the length of the adolescent romantic relationship was a significant positive predictor of the quality of adolescent romantic relationships (Dias & Ellis, 2022).

Two of the studies examined the relationship between adolescent romantic relationships and other important outcomes longitudinally. Dias and Ellis (2022) reported that although adolescent’s romantic relationship quality at time two was significantly correlated with parental support at time one, the results of the regression analyses showed that parental support at time one was not a significant predictor of romantic relationship quality at time two. Wright and Wachs (2021) found that the quality of adolescent’s romantic relationships at time one was positively related to quality at time two.

Discussion

Studies have established the importance of social relationships and one’s well-being (e.g., Goswami, 2012; Sun et al., 2020). A plethora of studies established that the parent-adolescent relationship is an important factor influencing adolescent psychological well-being (e.g., Paulsen & Berg, 2016; Wang et al., 2022). However, many studies have reported the importance of siblings (Buist et al., 2013; Gadassi Polack et al., 2021), peers (Hutchinson et al., 2021; Laurier et al., 2021), and romantic partners (Tamarit et al., 2020), too. The studies examined in this current manuscript offered valuable insight into how COVID affects key relationships in adolescents’ lives and the role of these relationships during the COVID lockdown.

COVID and adolescent-sibling relationships

Results from our review highlight the complexity of sibling relationships. Studies established that having siblings might help cope with the absence of peers (e.g., Milevsky, 2005), particularly during the lockdown period (Pediconi et al., 2021). Besides Cassinat et al. (2021) study which found a direct effect of family chaos in increasing sibling conflict from pre-COVID to the lockdown period, other studies suggest that the relationship between COVID and adolescents’ sibling relationships was moderated by various contextual factors, including the age of the adolescent, gender, and birth order. For example, Gadassi Polack et al. (2021) found that older adolescents in their sample (at T2, aged 13–17) reported a significant increase in positive interactions with their siblings, while younger youth in their sample (at T2: ages 9–12) did not. Similarly, Cassinat et al. (2021) found that the younger siblings (at T2: ages 11–15) in their sample reported declines in conflict with older siblings when comparing before and during the pandemic. In contrast, older siblings (at T2: ages 14–16) did not report significant changes in sibling conflict. Regarding gender of adolescent differences, Cassinat et al. (2021) reported that sibling relationship quality significantly declined from pre-COVID to during lockdown for boys as compared to girls. They also found that sibling disclosure significantly decreased from pre-COVID for boys compared to girls (Cassinat et al., 2021). Given that COVID restrictions and school closures left most adolescents with little options for face-to-face peer interaction, some adolescents, especially girls and those towards the beginning of adolescence (ages 12–15), seemed to have turned to their siblings for support and self-disclosure, possibly increasing intimacy and self-disclosure within sibling relationships.

On the other hand, it is likely that COVID operated through the various barriers and stressors (e.g., social distancing, school closures, etc.) it created. Thus, it is also possible that the increased stress from COVID (e.g., forced to stay home with family and siblings, etc.) was detrimental to positive sibling relationships (e.g., Cassinat et al., 2021). However, Campione-Barr et al. (2021) reported that COVID-related stress was not significantly related to positive or negative sibling relationships. Differences in samples, measures, and contexts could also account for the mixed findings across the three studies we found to review in this area.

Regarding the role of sibling relationships during COVID for adolescent outcomes, only one of the three studies selected assessed this. Close sibling relationships were only significantly associated with adolescent outcomes through significant interactions (rather than direct or main effects), such as higher levels of problem behavior when COVID-related stress was high (Campione-Barr et al., 2021). Given the dearth of studies examining the impact of COVID on sibling relationships during adolescence, especially the role of adolescent-sibling relationships during COVID, more studies are needed, particularly longitudinal studies that also assess family chaos, COVID-specific stressors or other aspects of stress on the family from COVID.

COVID and adolescent-peer relationships

Examination of the studies reviewed indicates mixed findings overall related to the changes in adolescents’ peer relationships during the COVID pandemic. Both of the correlational studies found positive effects of COVID on peer relationships for particular subgroups within their samples, particularly adolescent girls compared to boys (Zhu et al., 2022) and adolescents with somatic symptom disorders compared to adolescents who were hospitalized without somatic symptom disorder (Trombetta et al., 2022). These findings highlight the important possible moderating role of various contextual factors in relate to the COVID lockdown and changes in peer relationships among adolescents (e.g., gender, age, cultural values, health, etc.). For example, cultural values and contexts likely influenced the findings regarding adolescent relationships. As previous studies have established (e.g., Moller et al., 1992; Rose, 2002), girls invest more time in their friendships (communicating, self-disclosure). Having more time to communicate with their peers one-on-one (e.g., via text or FaceTime) may be more beneficial for adolescent girls, as suggested by Zhu et al. (2022).

Interestingly, both studies, which assessed peer relationships across time, found negative changes in peer relationships, including decreases in positive interactions with peers (Gadassi Polack et al., 2021) and increased peer conflict (Stevens et al., 2022). These negative effects are what one would expect to find when restrictions are placed on peer interactions, especially face-to-face, including the loss of opportunities for typical peer interaction at school and outside of the family home that occurred during the COVID lockdown for many families across the world. Another important finding in Stevens et al. (2022) study is the increases in peer relationship problems were more pronounced between T2 (peri-COVID; May–June 2020) and T1 (pre-COVID; Oct 2019-Jan 2020) than increases between T3 (post-COVID, peri-COVID second lockdown for the Netherlands; Nov 2020-Jan 2021) to T1(pre-COVID; Oct 2019-Jan 2020). It is possible that since the first lockdown, the use of communication through other methods besides face-to-face interactions, such as texting or calling via cellphones, social media such as TikTok, Instagram, WhatsApp, and other communication outlets such as video calls via Zoom, or FaceTime, and by the second lockdown, they are used to these alternative communication outlets. It is also possible that the COVID restrictions during T3 (the second lockdown in the Netherlands) are not as restrictive as during T2 (the first lockdown in the Netherlands).

It is also important to highlight the difference in changes (positive vs. negative) between these studies. One possible explanation is that both studies that reported negative changes (Gadassi Polack et al., 2021 and Stevens et al., 2022) used longitudinal data in which they compared pre- and peri-COVID. Trombetta et al. (2022) and Zhu et al. (2022) were both using correlational data. A longitudinal study, specifically comparing pre-, peri- and post-COVID, can provide a deeper understanding of the changes during this tumultuous period.

Another possible explanation is that the studies that found negative changes in adolescent peer relationships were all conducted in “Western” or individualistic countries such as the Netherlands (Stevens et al., 2022) and the U.S. (Gadassi Polack et al., 2021). On the other hand, the two studies with positive findings (i.e., China, Zhu et al., 2022; and Italy, Trombetta et al., 2022) were all conducted in countries considered to be more collectivistic (e.g., Oyserman et al., 2002; Triandis, 1995). Individuals growing up in individualistic cultures are more likely to be socialized toward individual goals and development, including autonomy and independence, and to view conflict as a healthy part of relationships (Bush & James, 2020; Oyserman et al., 2002; Trommsdorff & Kornadt, 2003). In contrast, adolescents in collectivistic countries are more likely to be socialized towards favoring goals of the in-group (e.g., family, etc.) and maintaining harmonious relationships (Bush & James, 2020; Oyserman et al., 2002; Trommsdorff & Kornadt, 2003). Thus, following these previous research findings, individualistic adolescents are likely to report conflict if present, while in contrast, adolescents living in collectivistic cultures/contexts are more likely to avoid conflict for the sake of fostering harmony with others and close relationships in general (Rothbaum et al., 2000; Trommsdorff & Kornadt, 2003). Peer relationships have also been found to differ in their role in adolescents’ lives across cultural value systems, with adolescents living in collectivistic cultures/contexts needing peer relationships to help guide their adaptation to cultural values (Tamm et al., 2018; Triandis, 1995). In contrast, the role of peer relationships among adolescents living in individualistic cultures/contexts focuses more on support from parents for their growing independence and autonomy (Bush & James, 2020; Tamm et al., 2018).

These findings also align with other general results from this review, suggesting possible cultural differences related to adolescent relationships. More specifically, Magis-Weinberg et al. (2021) report that the most endorsed concern associated with COVID within their Peruvian sample was related to family/friends getting sick, which aligns well with previous research highlighting the emphasis within collectivistic cultures/contexts on promoting harmony within their relationships and groups (Rothbaum et al., 2000; Trommsdorff & Kornadt, 2003). On the other hand, Magson et al. (2021) reported that friends or social connections were rated as the highest concern than any of the other COVID-related worries within their Australian sample, which is consistent with other research regarding the importance of peer relationships for adolescents in individualistic cultures/contexts (e.g., Tamm et al., 2018).

In regards to the role of peer relationships of adolescents during the COVID lockdown, the findings are also somewhat mixed, but all indicate either a positive role or no significant change. Three studies found that positive peer relations served to protect adolescents during the COVID lockdown (Hutchinson et al., 2021; Laurier et al., 2021; Magis-Weinberg et al., 2021); while two studies showed no significant effects of peer relationships on adolescent depressive symptoms, anxiety, and changes in life satisfaction (Magson et al., 2021) and mental health difficulties (Zhu et al., 2022). There are many factors that can influence these results, including socioeconomic status, cultural and gender differences, and individual resiliency.

COVID-19 and adolescent romantic relationships

Based on the results, it can be concluded that the changes in adolescent romantic relationships can vary from no changes to both positive changes; and that several factors might mediate or moderate these relationships, including income or socioeconomic status. Thus, the changes in adolescent romantic relationships during the COVID pandemic depend on several factors, making it difficult to make generalizations. More specifically, according to Pedrini et al. (2022), the COVID lockdown directly changed adolescent romantic relationships by decreasing perceived stress in romantic relationships. We also found that COVID-related stress at time one was not significantly related to the quality of adolescent romantic relationships at time two (Dias & Ellis, 2022). The first finding is counterintuitive, as one would expect the opposite (i.e., that COVID would increase stress). The second finding is a little surprising as one would expect COVID-related stress to be detrimental to adolescent adjustment, specifically adolescents' romantic relationships. In this case, it might be that adolescents were able to pivot to communicate and interact via cell phones, emails, and various social media (e.g., Wright and Wachs, 2021), which might have buffered adolescent’s relationships from COVID-related stress.

The cross-sectional results were also mixed and varied from no significant relationship between adolescent romantic relationships and COVID, to both positive and negative relationships. Three studies found that self-isolation and time away from romantic partners during COVID were negatively associated with adolescent romantic relationship quality (Karp et al., 2021; Wright and Wachs, 2021; Yarger et al., 2021), which supports the longitudinal findings noted above. Moreover, Karp et al. (2021) found that income loss was significantly associated with decreased relationship quality, compared to those who were not impacted economically by COVID. Examination of retrospective items found that while over 20% of adolescents across two studies reported their relationship decreased in closeness during COVID (Dias & Ellis, 2022; Karp et al., 2021); between 20 and 40% of adolescents reported that they became closer (Dias & Ellis, 2022) or their relationship increased in quality (Karp et al., 2021).

Examination of the results for what role adolescents romantic relationships might play during COVID indicated that adolescent romantic relationships were negatively significantly related to depression (Tamarit et al., 2020), positively related to technology used in relationship maintenance, and not significantly related to parental support (Dias & Ellis, 2022).

Given the mixed findings, it is important to keep in mind the various factors that are likely to be involved in mediating or moderating the relationships between COVID and adolescent romantic relationships, including income/SES noted here, as well as other possible factors such as cultural variables. More research is needed that can help determine what factors examined here, as well as others not included (e.g., measure of cultural values/impact), helped to either buffer adolescent romantic relationships or negatively change them during COVID. For example, what potential cultural values or practices might have helped buffer adolescent romantic relationships?

Conclusion

To conclude, our findings indicate that peer relationships seem to have experienced the most significant negative change during the COVID pandemic for adolescents, while relationships with siblings and parents seemed to have faired better. COVID had few direct impacts on adolescents’ relationships with siblings, rather, the significant change was moderated by various contextual factors, including gender, age, birth order, and culture. On the other hand, COVID did have detrimental impacts on adolescents’ relationships with peers, at least for adolescents living in individualistic cultures, while those living in collectivistic cultures experienced no change or positive changes in their peer relationships. Our examination of the changes in adolescent romantic relationships during the COVID pandemic also produced mixed findings, with a sizable proportion of adolescents experiencing negative outcomes with their romantic relationships (e.g., spent less time with them), while another significant proportion of adolescents experienced some positive outcomes related to their romantic relationship (e.g., closer relationships).

Overall, this current study makes important contributions to the literature by providing a groundwork for future research on the changes in adolescent relationships and the role of adolescent relationships in influencing adolescent outcomes during the lockdown period. The findings overall indicate that the COVID pandemic created some important barriers to maintaining adolescent relationships with siblings, peers, and romantic relationships (e.g., social isolation, social distancing, school closures, etc.). In turn, the COVID-related barriers produced higher levels of stress or family chaos, which then negatively changed adolescent relationships, especially peer relationships.

Recommendations (Policy/Practice)

Besides providing a groundwork for future research to understand the implications of COVID on adolescent relationships, this current study can shed some ideas for policymakers and practitioners in guiding and helping adolescents navigate the challenges during a stressful event. Understanding how COVID lockdown and isolation may affect adolescents in a unique way, and increasing accessibility to mental health services via alternative methods are crucial. This also means allocating resources, creating mental health education, whether through school or community, destigmatizing mental health issues, and creating more opportunities for community engagements in a safe way to allow them to still be connected with others. By creating these programs and providing them with coping strategies and resiliency, practitioners can work together with adolescents to mitigate the impact of COVID and support their overall well-being.

Limitations of study and direction for future research

While numerous studies were analyzed in this systematic review, a number of limitations were observed. First, this is a very new area, with limited longitudinal studies thus far, especially in the areas of sibling relationships and romantic relationships. Secondly, the studies selected utilized a wide variety of definitions and measurement techniques. For example, few studies directly measured relationships; most used proxy variables to represent healthy relationships, such as the presence or absence of conflict or intimacy. Thirdly, many of the findings across studies were mixed or contradictory, highlighting the important role of contextual variables that likely moderated many of the relationships examined here. Lastly, the studies reviewed here are from all over the globe; while this is a strength overall, it does lead to challenges in understanding the findings since none of the studies actually measured cultural values; thus, this had to be implied based on the country of origin and previous research.

References

Buhl, H. M. (2009). My mother: My best friend? Adults’ relationships with significant others across the lifespan. Journal of Adult Development, 16, 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9070-2

Buist, K. L., Deković, M., & Prinzie, P. (2013). Sibling relationship quality and psychopathology of children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.007

Bush, K.R. & James, A. (2020). Adolescence in individualist cultures. In Hupp, S. & Jewell, J. D. (Eds.), The Encyclopedia of Child and Adolescent Development. In Shek, D. and Leung, J. (Eds.), History, Theory, and Culture in Adolescence (vol. 7). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Campione-Barr, N., Rote, W., Killoren, S. E., & Rose, A. J. (2021). Adolescent adjustment during COVID-19: The role of close relationships and COVID-19-related stress. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 608–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12647

Carver, K., Joyner, K., & Udry, J. R. (2003). National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent Romantic Relations and Sexual Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practical Implications (pp 23–56). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cassinat, J. R., Whiteman, S. D., Serang, S., Dotterer, A. M., Mustillo, S. A., Maggs, J. L., & Kelly, B. C. (2021). Changes in family chaos and family relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 57(10), 1597–1610. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001217

Collins, W. A. (2003). More than myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.1301001

Collins, W. A., & Steinberg, L. (2008). Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Child and adolescent development: An advanced course (pp. 551–590). Wiley.

Conger, K. J., Conger, R. D., & Elder, G. H. (2020). Sibling relations during hard times. In Conger, R. D. (Ed.) (1994). Families in Troubled Times: Adapting to Change in Rural America. (pp. 235–252). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003058809

Davies, P. T., & Windle, M. (2000). Middle adolescents' dating pathways and psychosocial adjustment. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 46, 90– 118. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23093344

Dias, M., & Ellis, W. (2022). COVID-19 Stress and adolescent dating relationship quality: The moderating role of parental support. Western Undergraduate Psychology Journal, 10(1), 1–16.

Dirks, M. A., Persram, R., Recchia, H. E., & Howe, N. (2015). Sibling relationships as sources of risk and resilience in the development and maintenance of internalizing and externalizing problems during childhood and adolescence. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.07.003

Dotson, M. P., Castro, E. M., Magid, N. T., Hoyt, L. T., Suleiman, A. B., & Cohen, A. K. (2022). “Emotional distancing”: Change and strain in US young adult college students’ relationships during COVID-19. Emerging Adulthood, 10(2), 546–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968211065531

Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21(6), 1016–1024. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016

Gadassi Polack, R., Sened, H., Aubé, S., Zhang, A., Joormann, J., & Kober, H. (2021). Connections during crisis: Adolescents’ social dynamics and mental health during COVID-19. Developmental Psychology, 57(10), 1633–1647. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001211

Gass, K., Jenkins, J., & Dunn, J. (2007). Are sibling relationships protective? A longitudinal study. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01699.x

Golberstein, E., Wen, H., & Miller, B. F. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 819–820. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456

Goswami, H. (2012). Social Relationships and Children’s Subjective Well-Being. Social Indicator Research., 107, 575–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9864-z

Grover, R. L., Nangle, D. W., Serwik, A., & Zeff, K. R. (2007). Girl friend, boy friend, girlfriend, boyfriend: Broadening our understanding of heterosocial competence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36, 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410701651637

Grusec, J. E. (2002). Parental socialization and children’s acquisition of values. Handbook of Parenting, 5, 143–167.

Handel, G. (Ed.). (2011). Childhood socialization. Transaction Publishers.

Hutchinson, E. A., Sequeira, S. L., Silk, J. S., Jones, N. P., Oppenheimer, C., Scott, L., & Ladouceur, C. D. (2021). Peer connectedness and pre-existing social reward processing predicts US adolescent girls’ suicidal ideation during COVID-19. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 703–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12652

Jensen, A. C., Whiteman, S. D., Loeser, M. K., & Bernard, J. M. B. (2018). Sibling influences. In Levesque, R. J. R. (Ed.) (2018). Encyclopedia of adolescence (2nd ed.). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33228-4_37

Karp, C., Moreau, C., Sheehy, G., Anjur-Dietrich, S., Mbushi, F., Muluve, E., Mwanga, D., Nzioki, M., Pinchoff, J., & Austrian, K. (2021). Youth relationships in the era of COVID-19: A mixed-methods study among adolescent girls and young women in Kenya. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(5), 754–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.017

Killoren S. E., & Roach A. L. (2014). Sibling conversations about dating and sexuality: Sisters as confidants, sources of support, and mentors. Family Relations, 63(2), 232–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12057

Killoren S. E., Campione-Barr N., Streit C., Giron S., Kline G. C., Youngblade L. M. (2019). Content and correlates of sisters’ messages about dating and sexuality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(7), 2134–2155. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.miamioh.edu/10.1177%2F0265407518781039

Kramer, L., Conger, K. J., Rogers, C. R., & Ravindran, N. (2019). Siblings. In Fiese, B.H., Celano, M., Deater-Deckard, K., Jouriles, E.N., & Whisman, M.A. (Eds.), APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: Foundations, methods, and contemporary issues across the lifespan (pp. 521–538). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000099-029

Laurier, C., Pascuzzo, K., & Beaulieu, G. (2021). Uncovering the personal and environmental factors associated with youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: The pursuit of sports and physical activity as a protective factor. Traumatology, 27(4), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000342

Laursen, B., & Veenstra, R. (2021). Toward understanding the functions of peer influence: A summary and synthesis of recent empirical research. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(4), 889–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12606

Licoppe, C. (2004). Connected presence: The emergence of a new repertoire for managing social relationships in changing communication technoscape. Environment and Plan D: Social and Space., 22(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.1068/d323t

Lindell, A.K., & Campione-Barr, N. (2017). Relative power in sibling relationships across adolescence. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2017(156), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20201

Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A., ... & Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

Magis-Weinberg, L., Gys, C. L., Berger, E. L., Domoff, S. E., & Dahl, R. E. (2021). Positive and negative online experiences and loneliness in Peruvian adolescents during the COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 717–733. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12666

Magson, N. R., Freeman, J. Y., Rapee, R. M., Richardson, C. E., Oar, E. L., & Fardouly, J. (2021). Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9

Mancillas, A. (2011). Only children. In Caspi, J. (Ed.). Sibling development: Implications for mental health practitioners (pp. 341–358). Springer.

McHale, S. M., Updegraff, K. A., & Whiteman, S. D. (2012). Sibling relationships and influences in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(5), 913–930. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01011.x

Mervosh, S., Lu, D., Swales, V. (2020, April 20). See which states and cities have told residents to stay at home. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-stay-at-home-order.html. Accessed 20 Apr 2020

Milevsky, A. (2005). Compensatory patterns of sibling support in emerging adulthood: Variations in loneliness, self-esteem, depression, and life satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22(6), 743–755. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407505056447

Moller, L. C., Hymel, S., & Rubin, K. H. (1992). Sex typing in play and popularity in middle childhood. Sex Roles, 26, 331–353.

Morrissette, M. (2021). School closures and social anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.436

Oliva, A., & Arranz, E. (2005). Sibling relationships during adolescence. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 2(3), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620544000002

Orsmond, G. I., & Long, K. A. (2021). Family impact and adjustment across the lifespan: Siblings of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. In Glidden, L. M., Abbeduto, L., McIntyre, L. L., & Tassé, M. J. (Eds.), APA handbook of intellectual and developmental disabilities: Clinical and educational implications: Prevention, intervention, and treatment (pp. 247–280). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000195-010

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128(1), 3–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., ... & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

Paulsen, V., & Berg, B. (2016). Social support and interdependency in transition to adulthood from child welfare services. Children and Youth Services Review, 68, 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.07.006

Pediconi, M. G., Brunori, M., & Romani, S. (2021). From the inside. How the feelings of the closeness and the remoteness from others changed during lockdown. Psychology Hub, 38(3), 27–36.

Pedrini, L., Meloni, S., Lanfredi, M., Ferrari, C., Geviti, A., Cattaneo, A., & Rossi, R. (2022). Adolescents’ mental health and maladaptive behaviors before the Covid-19 pandemic and 1-year after: analysis of trajectories over time and associated factors. Child & Adolescent Psychiatry & Mental Health, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.miamioh.edu/10.1186/s13034-022-00474-x

Price, M., Hides, L., Cockshaw, W., Staneva, A., & Stoyanov, S. (2016). Young love: Romantic concerns and associated mental health issues among adolescent help-seekers. Behavioral Sciences, 6(2), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs6020009

Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000660

Reis, H. T., Lin, Y., Bennett, M. E., & Nezlek, J. B. (1993). Change and consistency in social participation during early adulthood. Developmental Psychology., 29(4), 633–645. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.633

Rittenour, C. E., Myers, S. A., & Brann, M. (2007). Commitment and emotional closeness in the sibling relationship. Southern Communication Journal., 72(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/10417940701316682

Rose, A.J. (2002). Co-rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Development, 73(6), 18–30–1843. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00509

Rothbaum, F., Pott, M., Azuma, H., Miyake, K., & Weisz, J. (2000). The development of close relationships in Japan and the United States: Paths of symbiotic harmony and generative tension. Child Development, 71, 1121–1142. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00214

Shulman, S. (2003). Conflict and negotiation in romantic relationships. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 109–136). Erlbaum.

Stevens, G. W. J. M., Buyukcan, T. A., Maes, M., Weinberg, D., Vermeulen, S., Visser, K., & Finkenauer, C. (2022). Examining socioeconomic disparities in changes in adolescent mental health before and during different phases of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Stress & Health, 39(1), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3179

Sun, J., Harris, K., & Vazire, S. (2020). Is well-being associated with the quantity and quality of social interactions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(6), 1478–1496. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000272

Tamarit, A., de la Barrera, U., Mónaco, E., Schoeps, K., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in Spanish adolescents: Risk and protective factors of emotional symptoms. Revista de Psicología Clínica Con Niños y Adolescentes, 7(3), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.21134/rpcna.2020.mon.2037

Tamm, A., Kasearu, K., Tulviste, T., & Trommsdorff, G. (2018). Links between adolescents’ relationships with peers, parents, and their values in three cultural contexts. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(4), 451–474. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.miamioh.edu/10.1177/0272431616671827

Toseeb, U. (2022). Sibling conflict during COVID‐19 in families with special educational needs and disabilities. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12451

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Westview Press.

Trombetta, A., De Nardi, L., Cozzi, G., Ronfani, L., Bigolin, L., Barbi, E., Bramuzzo, M., & Abbracciavento, G. (2022). Impact of the first COVID-19 lockdown on the relationship with parents and peers in a cohort of adolescents with somatic symptom disorder. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 48(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-022-01300-y

Trommsdorff, G., & Kornadt, H. J. (2003). Parent-child relations in cross-cultural perspective. In L. Kuczynski (Ed.), Handbook of dynamics in parent-child relations (pp. 271-306). Sage

Tsai, K. M., Telzer, E. H., & Fuligni, A. J. (2013). Continuity and discontinuity in perceptions of family relationships from adolescence to young adulthood. Child Development, 84(2), 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01858.x

Tucker, C. J., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2001). Conditions of sibling support in adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(2), 254–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.15.2.254

Valentine, G. (2006). Global intimacy: The role of information and communication technologies in maintaining and creating relationships. Women’s Studies Quarterly. 34(1), 365–393. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40004765

Van Dulmen, M., Goncy, E. A., Haydon, K. C., & Collins, W. A. (2008). Distinctiveness of adolescent and emerging adult romantic relationship features in predicting externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 336–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9245-8

Waite, E. B., Shanahan, L., Calkins, S. D., & Keane, S. P. (2011). Life events, sibling warmth, and youths’ adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(5), 902–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00857.x

Wang, M. T., Del Toro, J., Henry, D. A., Scanlon, C. L., & Schall, J. D. (2022). Family resilience during the COVID-19 onset: A daily-diary inquiry into parental employment status, parent–adolescent relationships, and well-being. Development and Psychopathology, 36(1), 312–324. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579422001213

Whiteman, S. D., Jensen, A. C., Mustillo, S. A., & Maggs, J. L. (2016). Understanding sibling influence on adolescents’ alcohol use: Social and cognitive pathways. Addictive Behaviors, 53, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.09.007

Whiteman S. D., Zeiders K. H., Killoren S. E., Rodriguez S. A., Updegraff K. A. (2014). Sibling influence on Mexican-origin adolescents’ deviant and sexual risk behaviors: The role of sibling modeling. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(5), 587–592. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.miamioh.edu/10.1016%2Fj.jadohealth.2013.10.004

Wright, M. F., & Wachs, S. (2021). Moderation of technology use in the association between self-isolation during COVID-19 pandemic and adolescents’ romantic relationship quality. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(7), 493–498. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.miamioh.edu/10.1089/cyber.2020.0729

Yarger, J., Gutmann-Gonzalez, A., Han, S., Borgen, N., & Decker, M. J. (2021). Young people’s romantic relationships and sexual activity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–10. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.miamioh.edu/10.1186/s12889-021-11818-1

Zhu, Q., Cheong, Y., Wang, C., & Sun, C. (2022). The roles of resilience, peer relationship, teacher–student relationship on student mental health difficulties during COVID-19. School Psychology, 37(1), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000492

Funding

We received no funding for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript has been seen and reviewed by both authors, and both authors have contributed to this paper in a meaningful way.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

No ethics approval is needed. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

This paper has not been published before, and it is not under consideration for publication anywhere else.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest/competing interests to report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murphy, L., Bush, K.R. A systematic review of adolescents’ relationships with siblings, peers, and romantic partners during the COVID-19 lockdown. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05842-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05842-8