Abstract

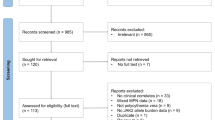

Hypercoagulability and reduced fibrinolysis are well-established complications associated with COVID-19. However, the timelines for the onset and resolution of these complications remain unclear. The aim of this study was to evaluate, in a cohort of COVID-19 patients, changes in coagulation and fibrinolytic activity through ROTEM assay at different time points during the initial 30 days following the onset of symptoms in both mild and severe cases. Blood samples were collected at five intervals after symptoms onset: 6–10 days, 11–15 days, 16–20 days, 21–25 days, and 26–30 days. In addition, fibrinogen, plasminogen, PAI-1, and alpha 2-antiplasmin activities were determined. Out of 85 participants, 71% had mild COVID-19. Twenty uninfected individuals were evaluated as controls. ROTEM parameters showed a hypercoagulable state among mild COVID-19 patients beginning in the second week of symptoms onset, with a trend towards reversal after the third week of symptoms. In severe COVID-19 cases, hypercoagulability was observed since the first few days of symptoms, with a tendency towards reversal after the fourth week of symptoms onset. A hypofibrinolytic state was identified in severe COVID-19 patients from early stages and persisted even after 30 days of symptoms. Elevated activity of PAI-1 and alpha 2-antiplasmin was also detected in severe COVID-19 patients. In conclusion, both mild and severe cases of COVID-19 exhibited transient hypercoagulability, reverted by the end of the first month. However, severe COVID-19 cases sustain hypofibrinolysis throughout the course of the disease, which is associated with elevated activity of fibrinolysis inhibitors. Persistent hypofibrinolysis could contribute to long COVID-19 manifestations.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, Relan P, Diaz JV (2022) A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis 22(4):e102–e107. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00703-9

Plášek J et al (2022) COVID-19 associated coagulopathy: mechanisms and host-directed treatment. Am J Med Sci 363(6):465–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjms.2021.10.012

Conway EM et al (2022) Understanding COVID-19-associated coagulopathy. Nat Rev Immunol 22(10):639–649. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00762-9

de Andrade Orsi FL, Campos Guerra JC (2020) Hipercoagulabilidade, eventos tromboembólicos e anticoagulação na COVID-19. Rev da Soc Cardiol do Estado São Paulo 30(4):462–471. https://doi.org/10.29381/0103-8559/20203004462-71

Zahran AM, El-Badawy O, Ali WA, Mahran ZG, Mahran EEMO, Rayan A (2021) Circulating microparticles and activated platelets as novel prognostic biomarkers in COVID-19; relation to cancer. PLoS ONE 16(2):e0246806. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246806

Whiting D, DiNardo JA (2014) TEG and ROTEM: technology and clinical applications. Am J Hematol 89(2):228–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.23599

Görlinger K et al (2021) The role of rotational thromboelastometry during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. Korean J Anesthesiol 74(2):91–102. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.21006

Gönenli MG, Komesli Z, İncir S, Yalçın Ö, Akay OM (2021) Rotational thromboelastometry reveals distinct coagulation profiles for patients with covid-19 depending on disease severity. Clin Appl Thromb 27:107602962110276. https://doi.org/10.1177/10760296211027653

Mazzeffi MA, Chow JH, Tanaka K (2021) COVID-19 associated hypercoagulability: manifestations, mechanisms, and management. Shock 55(4):465–471. https://doi.org/10.1097/SHK.0000000000001660

Wada H, Shiraki K, Shimpo H, Shimaoka M, Iba T, Suzuki-Inoue K (2023) Thrombotic mechanism involving platelet activation, hypercoagulability and hypofibrinolysis in coronavirus disease 2019. Int J Mol Sci 24(9):7975. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24097975

Hulshof A-M et al (2021) Serial EXTEM, FIBTEM, and tPA rotational thromboelastometry observations in the maastricht intensive care COVID cohort—persistence of hypercoagulability and hypofibrinolysis despite anticoagulation. Front. Cardiovasc Med 8:654174. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.654174

van Blydenstein SA et al (2021) Prevalence and trajectory of COVID-19-associated hypercoagulability using serial thromboelastography in a south african population. Crit Care Res Pract 2021:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/3935098

Toomer KH et al (2023) SARS-CoV-2 infection results in upregulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and neuroserpin in the lungs, and an increase in fibrinolysis inhibitors associated with disease severity. ejHaem 4(2):324–338. https://doi.org/10.1002/jha2.654

Polok K et al (2023) The temporal changes of hemostatic activity in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a prospective observational study. Polish Arch Intern Med. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.16446

Yoon U (2023) Native whole blood (TRUE-NATEM) and recalcified citrated blood (NATEM) reference value validation with ROTEM delta. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 27(3):108925322311515. https://doi.org/10.1177/10892532231151528

Meesters MI, Koch A, Kuiper G, Zacharowski K, Boer C (2015) Instability of the non-activated rotational thromboelastometry assay (NATEM) in citrate stored blood. Thromb Res 136(2):481–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2015.05.026

Schöchl H, Solomon C, Laux V, Heitmeier S, Bahrami S, Redl H (2012) Similarities in thromboelastometric (ROTEM®) findings between humans and baboons. Thromb Res 130(3):e107–e112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2012.03.

Ahmadzia HK et al (2021) Optimal use of intravenous tranexamic acid for hemorrhage prevention in pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 225(1):85.e1-85.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.11.035

Duca S-T, Costache A-D, Miftode R-Ș, Mitu O, Petriș A-O, Costache I-I (2022) Hypercoagulability in COVID-19: from an unknown beginning to future therapies. Med Pharm Rep 95(3):236–242. https://doi.org/10.15386/mpr-2195

Panigada M et al (2020) Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit: a report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost 18(7):1738–1742. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.14850

Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z (2020) Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 18(4):844–847. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.14768

Guan W et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 382(18):1708–1720. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

Huang C et al (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395(10223):497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

Ali N (2020) Elevated level of C-reactive protein may be an early marker to predict risk for severity of COVID-19. J Med Virol 92(11):2409–2411. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26097

Agrati C et al (2021) Elevated P-selectin in severe Covid-19: considerations for therapeutic options. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 13(1):e2021016. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2021.016

Aggarwal M, Dass J, Mahapatra M (2020) Hemostatic abnormalities in COVID-19: an update. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 36(4):616–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12288-020-01328-2

Corrêa TD et al (2020) Coagulation profile of COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU: an exploratory study. PLoS ONE 15(12):e0243604. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243604

Calvet L et al (2022) Hypercoagulability in critically ill patients with COVID 19, an observational prospective study. PLoS ONE 17(11):e0277544. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0277544

Ibañez C et al (2021) High D dimers and low global fibrinolysis coexist in COVID19 patients: what is going on in there? J Thromb Thrombolysis 51(2):308–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-020-02226-0

Mitrovic M et al (2021) Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) profiling of COVID-19 patients. Platelets 32(5):690–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537104.2021.1881949

van Veenendaal N, Scheeren TWL, Meijer K, van der Voort PHJ (2020) Rotational thromboelastometry to assess hypercoagulability in COVID-19 patients. Thromb Res 196:379–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2020.08.046

Boss K, Kribben A, Tyczynski B (2021) Pathological findings in rotation thromboelastometry associated with thromboembolic events in COVID-19 patients. Thromb J 19(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-021-00263-0

Kruse JM et al (2020) Thromboembolic complications in critically ill COVID-19 patients are associated with impaired fibrinolysis. Crit Care 24(1):676. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03401-8

Elaa A et al (2022) Assessment of coagulation profiles by rotational thromboelastometry in COVID 19 patients. Clin Lab 68(8):2022. https://doi.org/10.7754/Clin.Lab.2021.211026

Gando S, Levi M, Toh C-H (2016) Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Nat Rev Dis Prim 2(1):16037. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.37

Iba T, Levy JH (2020) Sepsis-induced coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Anesthesiology 132(5):1238–1245. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003122

Iba T, Levy JH, Thachil J, Wada H, Levi M (2019) The progression from coagulopathy to disseminated intravascular coagulation in representative underlying diseases. Thromb Res 179:11–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2019.04.030

Tsantes AG et al (2023) Sepsis-induced coagulopathy: an update on pathophysiology, biomarkers, and current guidelines. Life 13(2):350. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13020350

Sungurlu S, Kuppy J, Balk RA (2020) Role of antithrombin III and tissue factor pathway in the pathogenesis of sepsis. Crit Care Clin 36(2):255–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2019.12.002

Levi M, van der Poll T (2017) Coagulation and sepsis. Thromb Res 149:38–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2016.11.007

Degen JL, Bugge TH, Goguen JD (2007) Fibrin and fibrinolysis in infection and host defense. J Thromb Haemost 5:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02519.x

Creel-Bulos C et al (2021) Fibrinolysis shutdown and thrombosis in a COVID-19 ICU. Shock 55(3):316–320. https://doi.org/10.1097/SHK.0000000000001635

Wright FL et al (2020) Fibrinolysis shutdown correlation with thromboembolic events in severe COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Surg 231(2):193-203e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.05.007

Venkatesan P (2021) NICE guideline on long COVID. Lancet Respir Med 9(2):129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00031-X

Ambaglio C et al (2022) Role of hemostatic biomarkers for the identification of patients with LONG-COVID19 syndrome: results from the ‘Accordi’ study. Blood 140(Supplement 1):2652–2653. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2022-162206

Pretorius E et al (2021) Persistent clotting protein pathology in long COVID/post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin. Cardiovasc Diabetol 20(1):172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-021-01359-7

Baycan OF (2022) Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 levels as an indicator of severity and mortality for COVID-19. North Clin Istanbul. https://doi.org/10.14744/nci.2022.09076

Nougier C et al (2020) Hypofibrinolytic state and high thrombin generation may play a major role in SARS-COV2 associated thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost 18(9):2215–2219. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.15016

Whyte CS et al (2022) The suboptimal fibrinolytic response in COVID-19 is dictated by high PAI-1. J Thromb Haemost 20(10):2394–2406. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.15806

Kang S et al (2020) IL-6 trans-signaling induces plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 from vascular endothelial cells in cytokine release syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci 117(36):22351–22356. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2010229117

Zuo Y et al (2021) Plasma tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep 11(1):1580. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80010-z

Henry BM, Benoit SW, Hoehn J, Lippi G, Favaloro EJ, Benoit JL (2020) Circulating plasminogen concentration at admission in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Semin Thromb Hemost 46(07):859–862. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1715454

Gando S, Kameue T, Nanzaki S, Nakanishi Y (1996) Disseminated intravascular coagulation is a frequent complication of systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Thromb Haemost 75(02):224–228. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1650248

Zeerleder S, Schroeder V, Hack CE, Kohler HP, Wuillemin WA (2006) TAFI and PAI-1 levels in human sepsis. Thromb Res 118(2):205–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2005.06.007

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all individuals who participated in the study, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (HCFMUSP), to Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (FMUSP), CAPES and to all staff involved in the execution of the study.

Funding

Bárbara Gomes Barion received financial support from the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel Brazil (CAPES)—88887.679326/2023–00. This research was supported, in part, by a grant from the Brazilian Ministry of Health (plataformamaisbrasil 038018/2021), and part of study material was provided by Instrumentation Laboratory (Werfen).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Barion, B.G; Okazaki, E; Orsi, F.A; Investigation: Barion, B.G; Okazaki, E; Rocha,T.R.F; Ho, Yeh-Li; Rothschild, C; Fatobene, G; Moraes, B.G.C; Stefanello, B; Rocha, V.G; Villaça, P.R; Orsi, F.A; Formal analysis: Barion, B.G; Orsi, F.A; Resources: Rocha, V.G; Orsi, F.A; Writing: Barion, B.G; Okazaki, E; Rocha, T.R.F; Orsi, F.A; Final approval: Orsi, F.A

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Okazaki, E., Barion, B.G., da Rocha, T.R.F. et al. Persistent hypofibrinolysis in severe COVID-19 associated with elevated fibrinolysis inhibitors activity. J Thromb Thrombolysis 57, 721–729 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-024-02961-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-024-02961-8