Abstract

Stalking is a global spread phenomenon consisting in harassing, annoying, unwanted, and intrusive behaviors, often considered regular in courting. These behaviors are part of the broader range of gender-based violence. In accordance with the theory of ecological systems, this study aimed to investigate the presence of gender differences in the perception of the severity of stalking actions, considering the role of the type of violence perpetrated (physical versus verbal) and the relationship between the author and victim (Resentful ex-partner, Incompetent suitor rejected, Neighbor in dispute). The results showed gender differences in the main dimensions investigated by the questionnaire (Moral Disengagement, Normlessness beliefs, Empathy, and Perception of the Severity of Stalking). In addition, the results show that the perception of severity is influenced by the type of relationship and the type of violence perpetrated, differently between men and women. Results were discussed based on the development of literature on the topic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stalking is a global-spread phenomenon (Chan & Sheridan, 2020) characterized by repeated and harmless actions, which are considered regular in courting, such as sending messages, presents, or flowers, that may escalate into threatening and damaging behavior for the victim (Sinclair & Frieze, 2000). Stalking behavior is harassing, annoying, unwanted, and intrusive, and may cause the victim apprehension, distress, and fear for their life (Cailleau et al., 2018; Meloy & Felthous, 2011; Spitzberg & Cupach, 2003; Westrup & Fremouw, 1998). The most widely used definition is “obsessional following” from Meloy & Gothard (1995), which is at the same time also one of the broadest and consistent with international anti-stalking laws, including most stalking behaviors: “the willful, malicious, and repeated (obsessional) following and harassment of another person that threatens his or her safety” (p. 259).

The issues in defining stalking

Meloy and Gothard’s pioneering research provided the initial definition of stalking, laying the foundation for comprehending its root causes and diverse subtypes (Meloy & Gothard, 1995). Despite significant progress in the past three decades, a definitive theoretical model to explain stalking remains elusive. For instance, Attachment Theory, explained that individuals with insecure attachment resort to unhealthy coping mechanisms when faced with rejection or separation (Dykas & Cassidy, 2011; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019). Meloy (1996, 1997) suggests that insecure attachment can lead to the development of psychological traits associated with stalking. While numerous studies show a connection between stalking and insecure attachment, there’s ambiguity regarding the specific type, with differing views on preoccupied versus distancing attachment. The impact of attachment styles on stalking behavior is recognized as complex, prompting the need for a more precise theory that considers additional contributing factors (Parkhill et al., 2022). Another theory applied to stalking is the Social Learning Theory (SLT), proposing that stalking is learned behavior through observation and imitation, with correlations between stalking and educational experiences noted by Fox and colleagues (2011). However, despite potential applications (Parkhill et al., 2022), no recent research has explored SLT in the context of stalking.

Coercive Control Theory, emphasizing the need for control in stalking, has been referenced, but caution is advised to avoid circular reasoning. A 2018 study by Birch and colleagues examined stalking through information-processing theories of violence, acknowledging the role of cognitive processes and emotional regulation. Although this model is advancing, its ability to fully explain stalking is still developing.

Psychosocial consequences for the victims

Victims of stalking behaviors experience major effects on mental health, including high levels of post-traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety (Basile et al., 2004; Baum et al., 2009; Budd et al., 2000; Dovelius et al., 2006; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights., 2014; Fleming et al., 2012; Kamphuis et al., 2003; Kuehner et al., 2007; Matos et al., 2011; Miller, 2012; Pathé & Mullen, 1997; Podaná & Imríšková, 2016; Purcell et al., 2002, 2005; Thomas et al., 2008), as well as general well-being, including social, physical, and financial effects (Blaauw et al., 2002a; Brewster, 2003; Dreßing et al., 2020; Korkodeilou, 2017; Kuehner et al., 2012; Lacey et al., 2013; Logan & Cole, 2007; Logan & Walker, 2017; Pathé & Mullen, 1997; Worsley et al., 2017). In fact, exposure to persecutory conduct inflicts notable harm on victims’ physical and mental well-being, affecting social and occupational functioning (Kuehner et al., 2007; Matos et al., 2019; Villacampa & Pujols, 2019). Prolonged exposure to threats, particularly the loss of relational control and constant fear, significantly increases the risk of psychological impairment (Blaauw et al., 2002a, b; Baum et al., 2009). Stalking-induced traumatization can lead to psychiatric outcomes, with chronic emotional reactions like anger, fear, shame, and anxiety potentially culminating in pathology. Research has explored the role of individual differences in victims, considering both psychological vulnerability (McEwan et al., 2007) and coping strategies (functional vs. dysfunctional; Reyns & Englebreght, 2014; Villacampa & Pujols, 2019; Matos et al., 2019). The duration of harassment and the nature of the close relationship can impact the severity of repercussions. According to the cited literature, these consequences can refer to both physical and non-physical aggression, as various factors contribute to psychological consequences, including psychological vulnerability, the type of relationship and stalker, duration of stalking, and the nature of violence involved (threatened or physical).

Stalking behaviors are part of the broader range of gender-based violence phenomena, which can be explained by the Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1977) in its different declinations (Cho et al., 2012; Hollomotz, 2009; Laird, 2005; Sobsey, 2004; Thompson, 2020), and the understanding of risk factors for both perpetration and victimization behaviors.

The ecological systems theory for gender-based violence

According to Ecological Systems Theory, no single factor can explain why groups or individuals are at higher risk of victimization or have a greater propensity for perpetration. In Thompson’s (2006) ecological PCS model, he elucidates the origins of inequalities and discrimination within the cultural (C) and social (S) contexts surrounding an individual (P). At the core of the ecological model are the individual’s personal characteristics, encompassing factors such as age, gender, intellectual and physical abilities, ethnicity, sexuality, culture, religion, economic status, social class. The integration between Thompson’s PCS ecological model and Bronfenbrenner’s model (microsystem, mesosystem, macrosystem) allows us to understand that events, including episodes of violence, are not isolated occurrences. Instead, any changes at one level have consequences for the others.

The person, armed with self-defense skills, exists within a microsystem—the “home” environment. This microsystem comprises the immediate social circle of an individual, typically including family members, paid caregivers, and fellow residents in a residential setting. Studies indicate that most gender-based violence incidents occur within this microsystem (e.g., Keating, 2001; McCarthy, 1999; McCarthy & Thompson, 1996; Sobsey, 1994). As a result, it has been proposed that isolation and excessive protection within a microsystem are not effective strategies for preventing sexual violence (McCarthy, 1999; McCarthy & Thompson, 1996; Sobsey, 1994). The microsystem is part of an exosystem, which encompasses the broader environment surrounding the ‘home.’ This includes the neighborhood and social structures, incorporating various community activities like education, recreation, employment, and day-care. Ultimately, the exosystem is integrated into the macrosystem, which encompasses the broader society and culture. In Thompson’s (2006) PCS model, the cultural (C) and structural (S) aspects are distinct levels surrounding the personal level (P). However, the suggested ecological model incorporates both broader cultural and structural influences within the macrosystem. Thompson’s (2006) differentiation remains valuable for enhancing the understanding of the ecological risk model. He highlights that structural forces are more distant from individuals compared to cultural forces, making it challenging for individuals to exert influence over them.

Stalking itself can be understood as an established and perpetuated behavior resulting from the relationship between individual, interpersonal, societal, and cultural factors (Cho et al., 2012). As it happens in the sexual violence (Hollomotz, 2009; Thompson, 2020), three systems can be identified to explain the origin of risk in stalking behaviors:

-

Microsystem: including personal attributes (e.g., age, gender, sexuality, religion, …) and the individual’s immediate environment (e.g., family, social network, fellow residents, …).

-

Exosystem: including the environment, employment, and the accessed communities.

-

Macrosystem: including the societal and cultural factors.

Research suggests that most episodes of gender-based violence take place within the microsystem and that isolation within a microsystem can’t be considered an effective mechanism to prevent gender-based violence (Barchielli et al., 2021; Devries et al., 2013; Keating, 2001; Lausi et al., 2021b). The microsystem is strictly linked with the exosystem, consisting of the environment surrounding the “home”, and including all community activities, such as education, leisure, and employment. Finally, the macrosystem embeds both the exosystem and microsystem; it has been found that at societal and cultural level gender inequality seems to be a risk factor for many forms of gender-based violence; for instance, a higher incidence of gender-based violence has been found in societies where gender inequality is higher (Klevens & Ports, 2017; Lausi et al., 2021a; Redding et al., 2017; World Health Organization, 2009).

Classification of stalking and stalkers

Various categories of stalkers exist, each tied to the motives of the perpetrator or the complex dynamics between the perpetrator and the victim. One early classification by Wallis (1996) differentiated between “former intimates,” ending a romantic relationship with the victim, “casual stalkers,” who were friends or coworkers, and “unknown stalkers,” based on the level of intimacy in the relationship. Other classifications focus on psychiatric disorders; for instance, Zona et al. (1993) distinguish “the erotic,” “the love-obsessed,” and “the simply obsessed.” From a clinical viewpoint, Kienlen et al. (1997) separates psychotic stalkers from nonpsychotic ones, although the boundary between pathology-induced harassment and other motivations is not always clear.

One widely acknowledged classification posits stalking as a violent reaction to rejection, proposed by Mullen and colleagues (1999). They identify five stalker typologies:

-

1.

The Rejected Typology: Stalking arises from the breakdown of a close, often sexual, relationship. The initial motive is reconciliation, potentially shifting quickly to revenge against the one who ended the relationship.

-

2.

Intimacy Seeker Typology: This type targets strangers or acquaintances without prior emotional connections. Motivated by loneliness, the intimacy seeker believes in a connection with the person being stalked, irrespective of rejections.

-

3.

The Incompetent Suitor Typology: Like the intimacy seeker, individuals in this category target strangers or acquaintances but don’t assume an existing or destined relationship. Their motivation is loneliness or sexual desire.

-

4.

The Resentful Typology: Driven by a sense of mistreatment or victimization, these individuals seek revenge and justice, often collecting evidence of perceived injustices. Harassment by resentful stalkers tends to be prolonged.

-

5.

The Predatory Typology: Constituting a minority, this group stalks primarily to fulfill sadistic and/or sexual impulses. Stalking serves to gather information for potential acts of violence or sexual assault.

For the current research, the focus is on two types: the Resentful and the Incompetent Suitor.

Gender differences in judging stalking severity

A growing body of research has delved into the severity of stalking and its impact on victims. Notably, gender disparities have emerged, with female victims reporting heightened distress and perceived severity compared to males. According to Purcell and colleagues (2010), female victims often view stalking behaviors as more threatening than their male counterparts, potentially influenced by societal norms where women are more attuned to potential threats. Females tend to interpret actions such as unwanted gifts, surveillance, and threats as more severe and distressing (Sheridan et al., 2003). However, the findings are inconsistent and unclear. Situational variables like the nature of the relationship between the perpetrator and the victim (e.g., unknown suitor, ex-partner) and the type of violence perpetrated (verbal vs. physical) lack clear definitions. For example, some studies suggest that stalking is perceived differently when carried out by unknown individuals compared to known ones (Scott et al., 2010, 2014a, b; Scott & Sheridan, 2011). A study by Chung and Sheridan (2021) indicates that when the perpetrator is a stranger, the victim is more likely to feel frightened, and the crime is considered more serious. Conversely, when the perpetrator is a known person, especially a former partner, the victim is seen as more responsible for the experienced behavior. Furthermore, studies highlight gender-based variations in perceiving the severity of stalking. For example, women often perceive stalking threats, particularly from unknown suitors, as more serious than men do (Johnson et al., 2018). However, some studies suggest that gender may not significantly impact the perception of stalking severity, especially concerning variables such as the type of relationship between the perpetrator and the victim (Denninson and Thomson, 2002; ). In these instances, both males and females appear to assess the situation similarly. Another debated aspect is the type of violence involved in stalking, whether physical or verbal.

Sheridan and Scott (2010) discovered that women might rate verbal forms of stalking as more severe, while men might perceive physical violence as more dangerous. However, these results have not been further confirmed.

Numerous studies indicate that females generally exhibit higher levels of empathy compared to males. Others suggest only a small female advantage in empathic understanding (Kirkland et al., 2013; Warrier et al., 2018) These differences, particularly evident in tasks involving emotional recognition and verbal expressions of empathy, may be influenced by societal expectations and gender roles. The heightened empathy in females could play a crucial role in shaping distinct judgments about the severity of stalking.

From these premises, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 1

(H1). There are gender differences in empathy, moral disengagement, and judgments on specific stalking events.

Hypothesis 2

(H2). There are differences in the perception of the severity of the event due to the types of violence (Physical VS Verbal) and different types of stalking (Resentful ex-partner, Incompetent suitor rejected, Neighbor in dispute).

Method

Participants

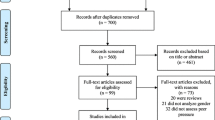

The participants included 312 participants (170 females and 142 males; women’s mean age: 26.02 ± 4.027 years; men’s mean age: 26.36, with Standard Deviation: 4.064 years) who had no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders based on their responses to a preliminary anamnestic questionnaire. All the participants had at least 13 years of education and provided their written informed consent before participating in the study.

Descriptive statistics were reported for gender, age, and education (Table 1).

Procedure and material

Participants completed an online questionnaire throughout the Qualtrics Survey Platform. A non-probabilistic and convenience sampling technique was used to successfully reach as many voluntary participants as possible. The questionnaire was spread via a variety of venues, including social networks, word-of-mouth, and the authors’ formal working platforms. Each respondent had the freedom to voluntarily opt to participate in the study and began completing the online survey after reading the informed consent. Maximum discretion was guaranteed in the handling and analysis of the responses. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of “Sapienza” the University of Rome and was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki.

An ad hoc online survey was developed to gather information on sociodemographic variables (i.e., gender, age, educational level, and occupation). The measurements listed in the following sections were part of the questionnaire.

Scenarios of verbal and physical violence

To evaluate the perceived severity of the stalking phenomenon, three real-case scenarios have been used in two different forms: the first one with acted violence and the second one with threatened violence (Supplementary material). Participants were therefore divided into two groups, the first group (N = 169, females N = 90; mean age = 26.36, SD = 4.064) read the threatened violence scenarios (i.e., “Mario approached aggressively, threatening to beat up his new partner”); the second group (N = 143, females N = 80; mean age = 26.02, SD = 4.027) read the same stories but with acted violence (i.e., “Mario approached aggressively beating up his new partner”). The two groups were no differences in age and gender (respectively for age: F1, 310 = 1,039, n.s.).

The three scenarios of stalking

The three stories described different real-life events, that were tried by Italian courts as Stalking offenses. Each presented a different type of stalking. The first was the story of a “resentful stalker”: an ex-wife harassed by her ex-husband. An “incompetent rejected suitor” was the character in the second story. The third tale reported on harassment perpetrated against a neighbor, following quarrels over a disputed boundary. The latter differed from the other stories because it presented a case of harassment of a man against a man (not a man against a woman) and there was no emotional relationship between the perpetrator and the victim (neighbor dispute).

Each scenario was followed by six questions that evaluated:

-

a)

The severity of the event (e.g.: “How serious do you consider Carlo’s actions to be?),

-

b)

The Moral justification (e.g.: “Do you believe that Carlo has been wronged to justify his behavior?”),

-

c)

Attribution of victim responsibility (e.g.: “Do you think Beatrice is to blame for Carlo’s reactions?”),

-

d)

Negative consequences for the perpetrator (e.g.: “Do you think Carlo’s behaviors will be punished by the law?”),

-

e)

Negative consequences for the victim (e.g.: “Do you think Beatrice may have consequences for her mental health because of Carlo’s behaviors?”),

-

f)

Need to help the victim (e.g.: “Do you think Beatrice should be helped by different professionals: police, health, social workers, etc.?”).

Each item was scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

Empathy

Furthermore, through the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) (Davis, 1980) we investigated the individual differences in empathy, that is, the reactions of one individual to the observed experiences of another (Davis, 1983). This questionnaire is a multidimensional measure that consists of four subscales: perspective taking (PT) measures the ability to shift to another person’s perspective, empathic concern (EC) measures other-oriented feelings of sympathy and concern for others, fantasy (FS) measures the tendency to become imaginatively absorbed in the feelings and actions of characters in books and movies, and personal distress (PD) measures self-oriented feelings of personal anxiety and uneasiness in tense interpersonal settings. 28 items answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Does not describe me well” to “Describes me very well”. IRI showed internal consistency with a Cronbach alpha for each subscale, respectively: 0.83 (PT), 0.82 (EC), 0.73 (FS), and 0.79 (PD).

Moral disengagement beliefs

The Moral Disengagement Beliefs instrument was validated in a study of Italian adolescents and adults by Caprara et al. (2006). The instrument assessed adolescents’ views of daily transgressive behaviors and comprised eight sets of four items, tapping onto one of the eight mechanisms or practices of moral disengagement (e.g., displacement of responsibility, attribution of blame, misconstruing the consequences) theorized by Bandura et al. (1990) for understanding the ways individuals might justify irreprehensible or morally questionable behaviors. (e.g., “if people leave their belongings around, it is their fault if someone steals them”). The validation study by Caprara et al. (2006) demonstrated that responses to these items converge on a single moral disengagement factor and that the instrument has very adequate construct and predictive validity. In the present study, adolescents’ response to each item was scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). For this Scale, the Cronbach alpha was 0.89.

Normlessness beliefs

Finally, the questionnaire also included four items measuring students’ beliefs about the possibility of violating socially acceptable norms of conduct or values (e.g., “you can do anything you want as long as you stay out of trouble”) (“Normlessness Scale”). For descriptive analyses, responses were averaged to create a scale score in which high scores signified high levels of normlessness beliefs. For structural equation modeling analyses, the four items were instead treated as single indicators of a latent construct of adolescents’ normlessness beliefs. For this Scale, the Cronbach alpha was 0.73.

Data analysis

Before conducting the data analyses, all variables were explored for accuracy of data entry and missing values. No missing data were found after conducting this estimation. The normality of all data was verified by the Shapiro-Wilk test and the homogeneity of variance was validated by the Levene test. The partial eta squared (i.e., ηp2) was used to determine the effect size. A value of 0.01 ηp2 indicates a small effect, a ηp2 of 0.06 indicates a medium effect and a ηp2 of 0.14 indicates a large effect size.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; version 25.0; IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA).

To verify gender differences (H1), we ran an Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the scores of the mono-factorial scales (Moral disengagement and Normlessness beliefs), with sex as the independent variable. At the same time, the scores of empathy subscales and scenario responses were submitted separately to Multivariate ANOVAs (MANOVAs) in association with Wilk’s Lambda test, with gender always as the independent variable.

To test our second hypothesis (H2), we submitted the severity rating to a Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, with Sex and Types of violence (Physical VS Verbal) as a between-subjects factor and the Severity judgment scores of the three stalking stories as a within‐subjects factor.

Results

Gender difference

The ANOVA of the Moral disengagement beliefs means scores revealed a significant effect of gender (F (1, 311) = 34.66, p < 0.001), showing significantly lower mean scores for women (Respectively: women mean = 1.30, DS 0.472; mean = 1,64, DS = 0.550; Table 2). A similar result for the ANOVA of the Normlessness beliefs, with a significant effect of gender (F (1, 311) = 13.43, p < 0.001), With women more inclined to respect rules (Respectively: women mean = 2.44, DS 0.576; men mean = 2.17, DS = 0.739).

The MANOVA of the IRI (Empathy)mean scores revealed a significant main effect of the gender for all the subscales (respectively, Fantasy: F (1, 310) = 24.28, p < 0.001; Perspective taking: F (1, 310) = 4.43, p < 0.036; Empathic concern: F (1, 310) = 13.94, p < 0.001; Personal distress: F (1, 310) = 26.87, p < 0.001). In all Empathy factors scores, the women proved to be more empathetic than men.

Women and men also differed significantly in their responses in all three scenarios. In the first scenario, we found gender-significant differences for Moral justification (F (1,310) = 17,92, p < 0.001), Attribution of victim responsibility (F (1,310) = 6,06, p < 0.05), Negative consequences for the victim (F (1,310) = 10,25, p < 0.01), Need to help the victim (F (1,310) = 8,36, p < 0.01). Otherwise, we found no differences in the Severity of the incident and Negative consequences for the perpetrator (Table 3).

In the second scenario, we found gender differences in all responses: Severity of the incident (F (1,310) = 7,83, p < 0.01), Moral justification (F (1,310) = 12,26, p < 0.001), Attribution of victim responsibility (F (1,310) = 8,63, p < 0.01), Negative consequences for the victim (F (1,310) = 10,7, p < 0.01), Need to help the victim (F (1,310) = 8,62, p < 0.01) and Negative consequences for the perpetrator (F (1,310) = 6,11, p < 0.01).

Finally, in the third scenario, we found gender differences for the Severity of the incident (F (1,310) = 7,06, p < 0.01), Moral justification (F (1,310) = 15,86, p < 0.001), Attribution of victim responsibility (F(1,310) = 4,03, p < 0.05), Negative consequences for the victim (F (1,310) = 22,55, p < 0.01), Need to help the victim (F (1,310) = 6,51, p < 0.05). and Negative consequences for the perpetrator (F (1,310) = 6,11, p < 0.01). We found no differences in Negative consequences for the perpetrator. Therefore, we found that women tend to be more empathetic with victims, use less moral disengagement mechanisms, and consider stalking actions more severe.

The role of different types of violence (Physical vs. Verbal) about gender and the impact of different types of stalking behaviors (e.g., Resentful ex-partner, Incompetent suitor rejected, Neighbor in dispute).

We found a significant effect of the interaction between “Type of Stalking” X “Types of Violence” (F (2,616) = 8,87, p < 0.001), but not for the interaction between “Type of Stalking” X “Sex”, and “Type of Stalking” X “Sex” X “Types of Violence”. Therefore, there is no gender difference in judging severity based on the type of violence. Women and men both judge physical action as more violent than verbal action (Tables 4a & 4b).

The ANOVA of Severity judgment scores Revealed a significant main effect of the Type of Stalking (F (2,616) = 145,19, p < 0.001). Respondents perceive the actions performed by the “Resentful ex-partner” as the most serious (M = 4.77, SD = 0.58), followed by the actions of the “Incompetent suitor rejected” (M = 4.38, SD = 0.76). Less serious are perceived as the actions of “Neighbors in dispute” (M = 4, SD = 0.88).

Discussion

Findings showed gender differences in the main dimensions investigated within the questionnaire (i.e., Moral disengagement, Normlessness beliefs, Empathy) with higher mean scores in women than men. Moreover, the responses among the three scenarios also seemed to be affected by the gender effect, particularly when investigating the severity of the stalking offense, the moral disengagement mechanisms, and the empathy toward victims.

Consistency with literature

These results are partially consistent with the literature. The perception of the severity of stalking appears to have undergone a transformation over time. In the early 1990s, the level of education was identified as a significant factor influencing how stalking was perceived (Baker et al., 1990). However, by the early 2000s, a shift occurred in the recognition of the phenomenon and its situational variables, revealing gender differences in the assessment of stalking (Blumenthal, 1998; Phillips et al., 2004; Rotundo et al., 2001). This evolution in perception can be attributed to the incorporation of stalking within the framework of gender-based violence behaviors in various manifestations (Cho et al., 2012; Hollomotz, 2009; Laird, 2005; Sobsey, 2004; Thompson, 2020). This broader conceptualization reflects an understanding that stalking is not only an isolated incident but is interconnected with broader issues related to gender-based violence. This change in perspective, coupled with the growing literature and research on the subject, leads us to hypothesize the need to consider new theoretical models for explaining the factors incorporated into our study. According to our premises, the Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1977) could coherently account for the phenomenon. Despite the data are clear in the light of the different theorized systems, it becomes evident that it is a need to deepen our understanding to more accurately identify the gap that results in partially unexpected outcomes.

However, the data can still be explained in the context of the Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). The macrosystem, i.e., social, and cultural processes, influences and acts on the perception of phenomena. According to this theory, women tend to be more empathetic due to a cultural issue of value transmission (Clarke et al., 2016; Nanda, 2013), as well as they will tend more to believe the victim and seek support for her (Broidy et al., 2003; Pinciotti & Orcutt, 2021); finally, due to cultural factors, women tend to adhere more to social norms rather than men.

Dual voice theory: exploring moral judgment differences

Women also seem more emotionally involved in moral choices (Gilligan, 1982; Boccia et al., 2014, 2017). In particular, Gilligan (1982) has developed the dual voice theory in moral judgment: men rationally solve moral dilemmas, that is, by respecting law and order (justice-based orientation). By contrast, women are driven by emotion, empathy, and care for others (care-based orientation). In line with such research, Cordellieri and colleagues (2020) have shown that women’s choices about moral dilemmas are much more influenced by processes of empathy with the victim. Furthermore, when the women assessed their emotional state after each dilemma, they showed a greater propensity to experience emotions such as sadness and fear. Therefore, women’s greater propensity to recognize the seriousness of stalking may not be due to the specific crime, but a generally greater empathic inclination toward victims of violence. Moreover, differences in the severity rating between verbal and physical violence were found. Particularly, the scenarios describing violent physical actions were perceived as more serious, as in Sheridan and Scott (2010), who showed how situational factors might have an important influence on stalking judgments and how physical abuse played a prominent role in decision-making.

Gender difference in evaluation of stalking actions

The first aim of our paper was to investigate whether there was a gender difference regarding the type of violence. We expected that women, more than men, judged stalking actions involving physical violence as more serious since they generally show less acceptance of physical violence (Bookwala et al., 1992). Our results disproved the possibility to identify a difference between women and men in evaluating stalking. This might be a perspective for future research in this field, to better understand the phenomenon. For instance, we differentiated verbal from physical violence through a single item, which may not be sufficient for respondents to identify with the victim. Otherwise, we must consider that the perception of severity is not mediated by the type of violence: physical vs. verbal.

Impact of relationship between perpetrator and victim

Regarding the relationship between perpetrator and victim, several studies showed that stalking is perceived as more serious when the perpetrator is a stranger rather than an acquaintance or ex-partner (Sheridan et al., 2003a, b; Phillips et al., 2004; Scott et al., 2010; Cass, 2011; Scott & Sheridan, 2011). Stalking is more likely rated as less severe when the abusive behavior was portrayed as an ex-partner, also enacting victim-blaming behaviors (Chung & Sheridan, 2021). On the contrary, our study found the stalking behaved by the ex-partner as the most severe one, followed by the “incompetent suitor rejected” and the “neighbor in dispute”. It can be hypothesized that those differences lie in the perpetrators’ behaviors. In our research, the ex-partner published intimate videos with the former partner; therefore, the violation of the intimacy experienced by the victim may play a crucial role.

Theoretical and practical contribution

In terms of practical implications, our research provides valuable insights for shaping educational initiatives, whether within a school or in any other context. When developing an educational project, it is essential to focus on a few key aspects.

First, it is crucial to cultivate a greater awareness of the true nature of stalking. Our questionnaire revealed instances where respondents did not demonstrate a clear understanding of the phenomenon. For example, some harassment was not perceived as violent actions capable of causing harm to victims. Therefore, the first important aspect is to make people aware of the consequences of harassing actions. To make people understand the psychological consequences for those who receive harassing acts.

Secondly, it is essential to address the issue of men’s lower propensity toward empathy. Our study shows that men show a lower ability to put themselves in the victim’s shoes, even when the victim is a man (third scenario), and are more likely to resort to mechanisms of moral exculpation. Psychoeducational activities should consider these aspects. It is not enough just to inform but also to act on the mechanisms of mirroring with the other. The use of virtual reality seems a promising scenario to counter gender-based violence (Johnston et al., 2023). VR is already getting some interesting applications (Virtual Reality Prevention of Gender-Violence in Europe based on Neuroscience of Embodiment, peRspective and Empathy, s.d.). Our research encourages such use.

Limitations and future perspectives

Our research has some limitations; however, these limitations provide a basis for future research on the topic. Firstly, the differences among scenarios, balanced by gender, could be further analyzed to ensure that no additional variables are overlooked in the investigation (e.g., privacy violation within the “ex-partner” scenario) that could potentially impact the results. To address this limitation, the questionnaire could be enhanced with new, more specific questions, aiming to make the scenarios as comparable as possible. Additionally, it’s essential to acknowledge that our study relied on a self-report questionnaire, introducing the potential for social desirability or recall biases. While we implemented necessary corrections during data pre-processing, some inherent risks persist, impacting the study’s reliability. However, the use of an anonymous questionnaire may mitigate this risk (Lajunen & Summala, 2003). Furthermore, we excluded data from scenarios deemed non-credible. To advance this research direction, creating more immersive and realistic scenarios is crucial. Despite these constraints, the study provides valuable insights into the evaluation of stalking behavior in the Italian context and sheds light on gender differences. This establishes a groundwork for future research, aiming to assess factors contributing more accurately to the potential underestimation of the phenomenon or victim-blaming.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study aimed to investigate gender differences in the perceived severity of certain stalking actions and psychological dimensions such as empathy and moral disengagement. The results supported our hypotheses, revealing significant gender differences between the various dimensions. Women demonstrated higher scores on empathy, showing greater empathic concern than men. In addition, women exhibited lower levels of beliefs of moral disengagement and lack of norms, suggesting stronger adherence to legal and ethical norms.

Scenarios describing different types of stalking further revealed gender variations in responses.

Women tended to perceive stalking actions as more serious, expressing less moral justification for perpetrators and showing greater inclination to help victims in all three scenarios. These findings align with the existing literature on gender differences in moral judgment and empathy, emphasizing the role of cultural and social factors (Gilligan, 1982; Cordellieri et al., 2020). Women’s greater propensity to recognize the severity of stalking may stem from a greater empathic inclination toward victims of violence.

Furthermore, our study delved into the impact of different types of violence (physical vs. verbal) and various stalking behaviors (resentful ex-partner, incompetent suitor rejected, neighbor in dispute) While both men and women rated physical actions as more violent than verbal actions, the perceived severity of the action was influenced by the type of stalking. Specifically, scenarios involving a resentful ex-partner were perceived as the most serious, followed by the actions of a rejected incompetent suitor and disputes between neighbors. In summary, our research contributes to the understanding of gender differences in judgments about stalking. The findings underscore the importance of considering both individual and situational factors in understanding the complex nature of responses to stalking events.

Further research is recommended to explore additional contextual factors and refine theoretical models to improve our understanding of gender-specific reactions to stalking phenomena.

Data availability

Generated Statement: The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

References

Baker, D. D., Terpstra, D. E., & Cutler, B. D. (1990). Perceptions of sexual harassment: A re-examination of gender differences. The Journal of Psychology, 124(4), 409–416.

Bandura, A., Pastorelli, C., Barbaranelli, C., & Caprara, G. V. (1999). Self-efficacy pathways to childhood depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 258–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.2.258.

Barchielli, B., Baldi, M., Paoli, E., Roma, P., Ferracuti, S., Napoli, C., Giannini, A. M., & Lausi, G. (2021). When stay at Home can be dangerous: Data on domestic violence in Italy during COVID-19 Lockdown. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 8948.

Basile, K. C., Arias, I., Desai, S., & Thompson, M. P. (2004). The differential association of intimate partner physical, sexual, psychological, and stalking violence and posttraumatic stress symptoms in a nationally representative sample of women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17(5), 413–421. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTS.0000048954.50232.d8.

Baum, K., Catalano, S., Rand, M., & Rose, K. (2009). National crime victimization survey: Stalking victimization in the United States.

Blaauw, E., Sheridan, L., & Winkel, F. W. (2002a). Designing anti-stalking legislation on the basis of victims’ experiences and psychopathology. Psychiatry Psychology and Law, 9(2), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1375/pplt.2002.9.2.136.

Blaauw, E., Winkel, F. W., Arensman, E., Sheridan, L., & Freeve, A. (2002b). The toll of stalking: The relationship between features of stalking and psychopathology of victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260502017001004.

Blumenthal, J. A. (1998). The reasonable woman standard: A meta-analytic review of gender differences in perceptions of sexual harassment. Law and Human Behavior, 22(1), 33–57.

Boccia, M., Cordellieri, P., Piccardi, L., Ferlazzo, F., Guariglia, C., & Giannini, A. M. (2014). Gender differences in solving moral dilemma: Are there any implications for experts in aerospace flight? Italian Journal of Aerospace Medicine, 10, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-014-0739-7.

Boccia, M., Dacquino, C., Piccardi, L., Cordellieri, P., Guariglia, C., Ferlazzo, F., Ferracuti, S., & Giannini, A. M. (2017). Neural foundation of human moral reasoning: An ALE meta-analysis about the role of personal perspective. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 11(1), 278–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-016-9505-x.

Bookwala, J., Frieze, I. H., Smith, C., & Ryan, K. (1992). Predictors of dating violence: A multivariate analysis. Violence and Victims, 7(4), 297–311.

Brewster, M. P. (2003). Stalking: Psychology, risk factors, interventions, and law. Civic Research Institute, Inc.

Broidy, L., Cauffman, E., Espelage, D. L., Mazerolle, P., & Piquero, A. (2003). Sex differences in empathy and its relation to juvenile offending. Violence and Victims, 18(5), 503–516.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513.

Budd, T., Mattinson, J., & Myhill, A. (2000). The extent and nature of stalking: Findings from the 1998 British Crime Survey. Citeseer.

Cailleau, V., Harika-Germaneau, G., Delbreil, A., & Jaafari, N. (2018). Le stalking: De La « Poursuite Romantique » à La prédation sexuelle. La Presse Médicale, 47(6), 510–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2018.03.002.

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Pastorelli, C., Iafrate, C., Beretta, M., Steca, P., & Bandura, A. (2006). La misura del disimpegno morale nel contesto delle trasgressioni dell’agire quotidiano. Giornale Italiano Di Psicologia, 33(1), 83–106. https://doi.org/10.1421/21961.

Cass, A. I. (2011). Defining stalking: The influence of legal factors, extralegal factors, and Particular actions on judgments of College Students. Western Criminology Review, 12(1), 1. http://www.westerncriminology.org/documents/WCR/v12n1/Cass.pdf.

Chan, H. C. & Sheridan, L. (Eds.). (2020). Psycho-criminological approaches to stalking behavior: An international perspective. Wiley.

Cho, H., Hong, J. S., & Logan, T. (2012). An ecological understanding of the risk factors Associated with stalking behavior: Implications for Social Work Practice. Affilia, 27(4), 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109912464474.

Chung, K. L., & Sheridan, L. (2021). Perceptions of stalking in Malaysia and England: The influence of perpetrator-target prior relationship and personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 182, 111064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111064.

Clarke, M. J., Marks, A. D., & Lykins, A. D. (2016). Bridging the gap: The effect of gender normativity on differences in empathy and emotional intelligence. Journal of Gender Studies, 25(5), 522–539.

Cordellieri, P., Boccia, M., Piccardi, L., Kormakova, D., Stoica, L., Ferlazzo, F., Guariglia, C., & Giannini, A. (2020). Gender differences in solving Moral dilemmas: Emotional Engagement, Care and Utilitarian Orientation. Psychological Studies, 65(4), 360–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-020-00573-9.

Dennison, S. M., & Thomson, D. M. (2002). Identifying stalking: The relevance of intent in commonsense reasoning. Law and Human Behavior, 26, 543–561. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020256022568.

Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y., Garcia-Moreno, C., Petzold, M., Child, J. C., Falder, G., Lim, S., Bacchus, L. J., Engell, R. E., & Rosenfeld, L. (2013). The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science, 340(6140), 1527–1528.

Dovelius, A., Holmberg, S., & Oberg, J. (2006). Swedish with an English summary). Stalking in Sweden: Prevalence and measures. Report.

Dreßing, H., Gass, P., Schultz, K., & Kuehner, C. (2020). The prevalence and effects of stalking. Deutsches Arzteblatt International. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2020.0347.

Dykas, M. J., & Cassidy, J. (2011). Attachment and the processing of social information across the life span: Theory and evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 137(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021367.

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2014). Violence against women:An EU wide survey: Main results. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2811/62230.

Fleming, K. N., Newton, T. L., Fernandez-Botran, R., Miller, J. J., & Burns, V. E. (2012). Intimate Partner Stalking victimization and posttraumatic stress symptoms in Post-abuse Women. Violence against Women, 18(12), 1368–1389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801212474447.

Fox, K. A., Nobles, M. R., & Akers, R. L. (2011). Is stalking a learned phenomenon? An empirical test of social learning theory. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(1), 39–47.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press.

Hollomotz, A. (2009). Beyond ‘Vulnerability’: An ecological Model Approach to conceptualizing risk of sexual violence against people with learning difficulties. British Journal of Social Work, 39(1), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm091.

ISTAT. (2016, November 24). Stalking sulle donne. https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/5348.

Johnson, P. A., Widnall, S. E., Benya, F. F., & Washington, D. C. (2018). Sexual harassment of women. Climate, culture, and consequences in academic sciences, engineering, and medicine. Washington (pp. 1–6). National Academy of Sciences.

Johnston, T., Seinfeld, S., Gonzalez-Liencres, C., Barnes, N., Slater, M., & Sánchez-Vives, M. V. (2023). Virtual reality for the rehabilitation and prevention of intimate partner violence – from brain to behavior: A narrative review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.788608.

Kamphuis, J. H., Emmelkamp, P. M. G., & Bartak, A. (2003). Individual differences in post-traumatic stress following post-intimate stalking: Stalking severity and psychosocial variables. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466503321903562.

Keating, J. (2001). Behind closed doors: Preventing sexual abuse against adults With a learning disability. UK Voice/Respond/MENCAP, London.

Kienlen, K. K., Birmingham, D. L., Solberg, K. B., & O’Regan, J. T. (1997). A comparative study of psychotic and nonpsychotic stalking. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 25(3), 317–334.

Kirkland, R. A., Peterson, E., Baker, C. A., Miller, S., & Pulos, S. (2013). Meta-analysis reveals adult female superiority in reading the mind in the eyes test. North American Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 121–146.

Klevens, J., & Ports, K. A. (2017). Gender Inequity Associated with increased child physical abuse and neglect: A Cross-country Analysis of Population-based surveys and Country-Level statistics. Journal of Family Violence, 32(8), 799–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-017-9925-4.

Korkodeilou, J. (2017). No place to hide’: Stalking victimisation and its psycho-social effects. International Review of Victimology, 23(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269758016661608.

Kuehner, C., Gass, P., & Dressing, H. (2007). Increased risk of mental disorders among lifetime victims of stalking – findings from a community study. European Psychiatry, 22(3), 142–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.09.004.

Kuehner, C., Gass, P., & Dressing, H. (2012). Mediating effects of stalking victimization on Gender Differences in Mental Health. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(2), 199–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260511416473.

Lacey, K. K., McPherson, M. D., Samuel, P. S., Sears, P., K., & Head, D. (2013). The impact of different types of intimate Partner violence on the Mental and Physical Health of women in different ethnic groups. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(2), 359–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260512454743.

Laird, S. E. Anti-Discriminatory Practice, * Neil Thompson, *, & London, P. M. (2005). 2006, pp. 208, ISBN 13 978 1 4039 2160 4, 17.99. British Journal of Social Work, 36(6), 1061–1062. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl092.

Lajunen, T., & Summala, H. (2003). Can we trust self-reports of driving? Effects of impression management on driver behaviour questionnaire responses. Transportation Research part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 6(2), 97–107.

Lausi, G., Burrai, J., Barchielli, B., Quaglieri, A., Mari, E., Fraschetti, A., Paloni, F., Cordellieri, P., Ferlazzo, F., & Giannini, A. M. (2021a). Gender pay gap perception: A five-country European study. SN Social Sciences, 1(11), 267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00274-8.

Lausi, G., Pizzo, A., Cricenti, C., Baldi, M., Desiderio, R., Giannini, A. M., & Mari, E. (2021b). Intimate Partner violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the phenomenon from victims’ and help professionals’ perspectives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6204. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126204.

Logan, T., & Cole, J. (2007). The Impact of Partner Stalking on Mental Health and Protective Order outcomes over Time. Violence and Victims, 22(5), 546–562. https://doi.org/10.1891/088667007782312168.

Logan, T., & Walker, R. (2017). Stalking: A Multidimensional Framework for Assessment and Safety Planning. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 18(2), 200–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015603210.

Matos, M., Grangeia, H., Ferreira, C., & Azevedo, V. (2011). Inquérito de vitimação por stalking: Relatório de investigação.

Matos, M., Grangeia, H., Ferreira, C., Azevedo, V., Gonçalves, M., & Sheridan, L. (2019). Stalking victimization in Portugal: Prevalence, characteristics, and impact. International Journal of law Crime and Justice, 57, 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2019.03.005.

McCarthy, M. (1999). Sexuality and women with learning disabilities. Jessica Kingsley.

McCarthy, M., & Thompson, D. (1996). Sexual abuse by design: An examination of the issues in learning disability services. Disability & Society, 11(2), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599650023236.

McEwan, T., Mullen, P. E., & Purcell, R. (2007). Identifying risk factors in stalking: A review of current research. International Journal of law and Psychiatry, 30(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2006.03.005.

Meloy, J. R. (1996). Stalking (obsessional following): A review of some preliminary studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 1(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/1359-1789(95)00013-5.

Meloy, R. J. (1997). Violent attachments. Jason Aronson.

Meloy, J. R., & Felthous, A. (2011). Introduction to this issue: International perspectives on stalking. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 29(2), 139–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.982.

Meloy, J. R., & Gothard, S. (1995). Demographic and clinical comparison of obsessional followers and offenders with mental disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(2), 258–263. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.152.2.258.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2019). Attachment orientations and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.006.

Miller, L. (2012). Stalking: Patterns, motives, and intervention strategies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(6), 495–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.07.001.

Mullen, P. E., Pathé, M., Purcell, R., & Stuart, G. W. (1999). Study of stalkers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(8), 1244–1249. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.156.8.1244.

Nanda, S. (2013). Are there gender differences in empathy. Psychology at Berkeley, 32.

Parkhill, A. J., Nixon, M., & McEwan, T. E. (2022). A critical analysis of stalking theory and implications for research and practice. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 40(5), 562–583. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2598.

Pathé, M., & Mullen, P. E. (1997). The impact of stalkers on their victims. British Journal of Psychiatry, 170(1), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.170.1.12.

Phillips, L., Quirk, R., Rosenfeld, B., & O’Connor, M. (2004). Is it stalking? Perceptions of stalking among college undergraduates. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 31(1), 73–96.

Pinciotti, C. M., & Orcutt, H. K. (2021). Understanding gender differences in rape victim blaming: The power of social influence and just world beliefs. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1–2), 255–275.

Podaná, Z., & Imríšková, R. (2016). Victims’ responses to stalking: An examination of fear levels and coping strategies. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(5), 792–809. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514556764.

Purcell, R., Pathé, M., & Mullen, P. E. (2002). The prevalence and nature of stalking in the Australian Community. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(1), 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.00985.x.

Purcell, R., Pathé, M., & Mullen, P. E. (2005). Association between stalking victimisation and psychiatric morbidity in a random community sample. British Journal of Psychiatry, 187(5), 416–420. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.187.5.416.

Purcell, R., Pathé, M., & Mullen, P. (2010). Gender differences in stalking behaviour among juveniles. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 21(4), 555–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940903572035.

Redding, E. M., Ruiz-Cantero, M. T., Fernández-Sáez, J., & Guijarro-Garvi, M. (2017). Gender inequality and violence against women in Spain, 2006–2014: Towards a civilized society. Gaceta Sanitaria, 31(2), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.07.025.

Reyns, B. W., & Englebrecht, C. M. (2014). Informal and formal help-seeking decisions of stalking victims in the United States. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41(10), 1178–1194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854814541441.

Rotundo, M., Nguyen, D. H., & Sackett, P. R. (2001). A meta-analytic review of gender differences in perceptions of sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 914.

Scott, A. J., & Sheridan, L. (2011). Reasonable’perceptions of stalking: The influence of conduct severity and the perpetrator–target relationship. Psychology Crime & Law, 17(4), 331–343.

Scott, A. J., Lloyd, R., & Gavin, J. (2010). The influence of prior relationship on perceptions of stalking in the United Kingdom and Australia. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(11), 1185–1194.

Scott, A. J., Rajakaruna, N., & Sheridan, L. (2014a). Framing and perceptions of stalking: The influence of conduct severity and the perpetrator–target relationship. Psychology Crime & Law, 20(3), 242–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2013.770856.

Scott, A. J., Rajakaruna, N., Sheridan, L., & Sleath, E. (2014b). International perceptions of stalking and responsibility: The influence of prior relationship and severity of behavior. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41(2), 220–236.

Sheridan, L., & Scott, A. J. (2010). Perceptions of harm. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(4), 400–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854809359743.

Sheridan, L., Gillett, R., Davies, G. M., Blaauw, E., & Patel, D. (2003a). There’s no smoke without fire’: Are male ex-partners perceived as more ‘entitled to’ stalk than acquaintance or stranger stalkers? British Journal of Psychology, 94(1), 87–98.

Sheridan, L. P., Blaauw, E., & Davies, G. M. (2003b). Stalking: Knowns and unknowns. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 4(2), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838002250766.

Sinclair, H. C., & Frieze, I. H. (2000). Initial courtship behavior and stalking: How should we draw the line? Violence and Victims, 15(1), 23–40.

Sobsey, D. (1994). Sexual abuse of individuals with intellectual disability. In A. Craft (Ed.), Practice issues in sexuality and learning disabilities. Routledge.

Sobsey, D. (2004). Sexual abuse of individuals with intellectual disability. Practice issues in sexuality and learning disabilities (pp. 91–112). Routledge.

Spitzberg, B. H., & Cupach, W. R. (2003). What mad pursuit? Obsessive relational intrusion and stalking related phenomena. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 8(4), 345–375.

Thomas, C., Hypponen, E., & Power, C. (2008). Obesity and type 2 diabetes risk in midadult life: The role of childhood adversity. PEDIATRICS, 121(5), E1240–E1249. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-2403.

Thompson, N. (2006). Anti-discriminatory practice (4th ed.). Basingstoke.

Thompson, N. (2020). Anti-discriminatory practice: Equality, diversity and social justice. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Villacampa, C., & Pujols, A. (2019). Effects of and coping strategies for stalking victimisation in Spain: Consequences for its criminalisation. International Journal of Law Crime and Justice, 56, 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2018.11.002.

Virtual Reality Prevention of Gender-Violence in Europe based on Neuroscience of Embodiment, peRspective and Empathy (s.d.). University of Jyväskylä. https://www.jyu.fi/en/projects/virtual-reality-prevention-of-gender-violence-in-europe-based-on-neuroscience-of-embodiment.

Wallis, M. (1996). Outlawing stalkers: See party politics put to one side as politicians seek to make new laws to empower the police to deal more effectively with stalkers. Policing Today, 2, 25–29.

Warrier, V., Grasby, K. L., Uzefovsky, F., Toro, R., Smith, P., Chakrabarti, B., Khadake, J., Mawbey Adamson, E., Litterman, N., Hottenga, J. J., Lubke, G., Boomsma, D. I., Martin, N. G., Hatemi, P. K., Medland, S. E., Hinds, D. A., Bourgeron, T., & Cohen, B., S (2018). Genome-wide meta-analysis of cognitive empathy: Heritability, and correlates with sex, neuropsychiatric conditions and cognition. Molecular Psychiatry, 23, 1402–1409.

Westrup, D., & Fremouw, W. J. (1998). Stalking behavior: A literature review and suggested functional analytic assessment technology. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 3(3), 255–274.

World Health Organization (2009). Promoting gender equality to prevent violence against women.

Worsley, J. D., Wheatcroft, J. M., Short, E., & Corcoran, R. (2017). Victims’ voices: Understanding the emotional impact of Cyberstalking and individuals’ coping responses. SAGE Open, 7(2), 215824401771029. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017710292.

Zona, M. A., Sharma, K. K., & Lane, J. (1993). A comparative study of erotomanic and obsessional subjects in a forensic sample. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 38(4), 894–903.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cordellieri, P., Paoli, E., Giannini, A.M. et al. From verbal to physical violence: the different severity perception of stalking behaviors. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05834-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05834-8