Abstract

Social media addiction has previously been linked to compromised mental health and social isolation; however, most studies are cross-sectional or based on convenience samples. The objective of the current study was to assess the extent to which social media addiction predicts compromised mental health and social isolation (including bi-directionality) in a large prospective sample of Danish adults. Data stem from a nationwide longitudinal Danish survey of 1958 adults (aged 16+) conducted in 2020 and 2021. The Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS) was used. Validated scales were used to assess depression, mental wellbeing, and loneliness. A total of 2.3% screened positive for social media addiction. As compared to no symptoms, social media addiction was associated with an elevated risk for depression (OR = 2.71; 95% CI 1.08, 6.83) and negatively with mental wellbeing (coef = −1.29; 95% CI −2.41, −0.16). Similarly, social media addiction was associated with an elevated risk of loneliness (OR = 4.40; 95% CI 1.20, 16.19), and negatively with social network size (coef = −0.46; 95% CI −0.86, −0.06). There is a need for preventive actions against addictive social media use, as this poses significant risk to mental health and social functioning in the working age population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mental disorders are a major issue, affect a substantial proportion of the global population, and have been increasing globally since 1990 (GBD, 2022). They affect more than 1 billion people worldwide, causing 7% of the global disease burden, and 19% of years lived with disability (Rehm & Shield, 2019). Disability-adjusted life years attributable to mental disorders are overwhelmingly caused by common mental disorders (CMDs), e.g., depression (Rehm & Shield, 2019; WHO, 2017), which are associated with both excess of deaths and premature mortality from injuries and chronic illnesses (Charlson et al., 2016; Plana-Ripoll et al., 2019; Prince et al., 2007). In parallel, other reports have documented global declines in indicators of wellbeing since 2016 (Helliwell et al., 2022).

Moreover, social isolation is a pervasive societal problem, that can contribute to morbidity and mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015; Santini, Jose, et al., 2020), and is experienced by a substantial proportion of the population in many countries (Surkalim et al., 2022). Perceived social isolation, also commonly referred to as loneliness, refers to a perceived discrepancy between actual and desired social contacts (Cacioppo et al., 2010). Objective social isolation refers to non-existing or a very limited number of social contacts. All of these factors can be considered as unfulfilled basic social needs, and while transient social isolation is a common experience, chronic or severe social isolation poses serious threats to the mental health and wellbeing of people of all ages (Surkalim et al., 2022). Over the past decades, Denmark has seen both increases in poor mental health and mental health problems (Jeppesen et al., 2020; SST, 2022) and also declines in higher levels of wellbeing (Santini et al., 2021). Simultaneously, social isolation has doubled over the past two decades (Girault et al., 2023).

Behavioral Addictions and Addictive Social Media Use

Social media use is now widespread across the globe, used by one in three people worldwide and more than two-thirds of all Internet users (Ortiz-Ospina, 2019). The rapid and vast adoption of social media technologies has changed how people communicate with others, find partners, access information, and engage in public debate. While general social media use is associated with both drawbacks and benefits to mental and social wellbeing (Verduyn et al., 2017; Zsila & Reyes, 2023), it can also lead to addictive social media use. Social media platforms have long been suspected of deriving hefty profits through addictive social media algorithms, with recent estimates suggesting that platforms generate billions of dollars in annual revenue from vulnerable population segments (youth users in particular) (Raffoul et al., 2023). In addition, malicious third parties capitalize on addictive social media use as a means to exploit and scam users, compounding the risks and posing significant threats to users' privacy and safety (Bharne & Bhaladhare, 2023; Grubb, 2020). Social media addiction (also referred to as “compulsive social media use,” “social media disorder,” “problematic social media use,” and “problematic social networking”; Aladwani & Almarzouq, 2016; Huang, 2022; van den Eijnden et al., 2018; Vernon et al., 2017) involves social media use, where core components of addiction are present. These are (1) salience (preoccupation, craving), (2) mood modification (engaging in an addictive behavior to achieve a high or as a coping method), (3) tolerance (when increasing amounts of the behavior is needed to achieve mood-modifying effects), (4) withdrawal symptoms (unpleasant feelings or physical effects when not engaging in the behavior), (5) conflict (conflicts experienced with other people or other activities, or internal conflicts about the addictive behavior), and (6) relapse (failed attempts to limit or reduce the addictive behavior) (Griffiths, 2005). It is argued that social media addiction and related internet addictions function similarly to other behavioral addictions, such as pathological gambling (Jiang, 2022). It is important to note that social media addiction is not a recognized clinical disorder in the DSM-5 or ICD-11, and there is ongoing debate that a classification of social media addiction as a disorder may run the risk of pathologizing normal behavior. While the focus of the current study is on addictive social media use as an exposure of interest, discussions surrounding its validity as a diagnosable addiction disorder may be found elsewhere (Castro-Calvo et al., 2021; Fournier et al., 2023).

Social Media Addiction and Links to Mental Health or Social Isolation

Huang (2022) conducted a systematic review on the link between problematic social media use and mental health across 122 studies. The results from the meta-analysis showed that problematic social media use correlated positively with psychological distress (e.g., depression) and loneliness, and negatively with wellbeing. The vast majority of these studies were cross-sectional (which limits direction of causality inference) and conducted on relatively small student or convenience samples (e.g., digital surveys distributed through social media). Only nine studies, to our knowledge, have assessed longitudinal relationships specifically between social media addiction symptoms and mental health and social isolation outcomes (see the appendix for an expanded review of the following studies, Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2017; Chen et al., 2020; Di Blasi et al., 2022; Marttila et al., 2021; Muusses et al., 2014; Raudsepp, 2019; Raudsepp & Kais, 2019; van den Eijnden et al., 2018; Vernon et al., 2017). Most of the studies indicate that social media addiction symptoms are associated with increased risk for compromised mental health and social isolation, but three of the studies did not find evidence of associations with some measures of wellbeing (life satisfaction) (Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2017; Marttila et al., 2021), social isolation-related constructs (social support) (Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2017), and mental health problems (depression, anxiety, stress) (Di Blasi et al., 2022).

The Present Study

More research is needed to build on the evidence base, as studies documenting longitudinal results from large nationwide survey data are scarce. There is a need to assess associations between social media addiction and a variety of such outcomes, as a means to generate more robust estimates and advance current knowledge. Using data from a large, nationwide survey representative of the adult population (aged 15–64 years old) in education or employment in Denmark (restricted to this population because the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale – BSMAS – used in this study is framed specifically to people in education or employment), we set out to investigate the extent to which social media addiction (symptoms and above cut-point) predicts depression, mental wellbeing, loneliness, and social network size one year after baseline social media addiction assessment.

Following the reviewed studies, we hypothesized that (1) each increase in the number of social media addiction symptom score would be positively related with depression and loneliness at follow-up and negatively related with mental wellbeing and social network size at follow-up, and that (2) social media addiction (above cut-point), as compared to those with no symptoms, would be associated with increased risk for depression and loneliness at follow-up, while showing an inverse association with mental wellbeing and social network size at follow-up. Our analytic approach will also account for the possibility of a bi-directional relationship between mental health and social isolation as predictors in 2020 (depression, mental wellbeing, loneliness, network size) and social media addiction in 2021. The study has both theoretical and practical implications. In terms of the theoretical contribution, the study would add to the literature on etiological models of dual diagnosis (Moggi, 2005), for example with regard to direct, indirect, and bi-directional models. In terms of practical contributions, the study may inform universal or targeted interventions to address the negative impact of social media addiction symptoms on mental health and social connectedness, as well as policies to restrict addictive social media algorithms, or strategies for promoting digital literacy and responsible social media usage as a means to cultivate healthier online habits and to mitigate addiction risks.

Methods

Sampling and Data Collection

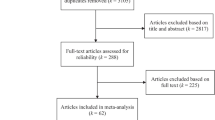

The Danish Health and Wellbeing Survey (Rosendahl Jensen et al., 2021) is the Danish part of the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS). Everyone with residence in Denmark has a personal identification number which is used throughout administrative registers and stored in the Civil Registration System (Pedersen, 2011; Thygesen et al., 2011). From the Civil Registration System, participants 15 years or more (In Denmark, 15 years is the age of consent with regard to survey participation) were invited in 2020 and again in 2021. The selection of study participants is illustrated in a flow chart in Fig. 1. The follow-up sample was then restricted to (1) standard working age of less than 65 years old individuals who were either studying or employed at the time of the 2020 survey, since the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale – BSMAS – questionnaire measures symptoms of social media addiction specifically among people in education or employment (i.e., item 6 - negative impact on work/studies), and (2) only participants who reported being social media users. The restriction of the sample resulted in a final sample size of 1958 participants. The study design and the data collection methods have been described in detail elsewhere (Rosendahl Jensen et al., 2022).

The survey data were linked on an individual level to administrative registers at Statistics Denmark’s research server, which allows for the merging of data on educational level, ethnicity, income, health status, and healthcare utilization, among other variables. All data are pseudonymized to hinder the possibility of tracing it back to specific participants. The study was approved by the University of Southern Denmark’s (SDU’s) Research & Innovation Organisation (RIO) (ID 11.107). SDU RIO examines and approves all scientific and statistical projects at the University of Southern Denmark according to the Danish Data Protection Regulation. Ethical approval is not required for surveys according to Danish legislation. The study complies with the Helsinki 2 Declaration on Ethics.

Exposure: Social Media Addiction

The Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS) (Andreassen et al., 2017) was used to assess social media addiction symptoms. The 6-item scale is a modified version of the previously validated Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS) (Andreassen et al., 2012), where the modification involves using the words “social media” instead of the word “Facebook,” with social media being defined as “Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and the like” in the instructions. The original scale (i.e., BFAS) was translated into several languages and has shown good psychometric properties (Andreassen et al., 2012). The BSMAS has subsequently been validated in the working age general population in various cultural settings (Zarate et al., 2023). The scale’s internal reliability in the present study was high (α = 0.83; ω = 0.84). The modified 6-item BSMAS scale assesses social media addiction symptoms within the past 12 months. The scale incorporates the theoretical framework of the addiction components (i.e., salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, conflict, and relapse) of the biopsychosocial model (Griffiths, 2005). Participants rate these items using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1=very rarely, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=often, and 5=very often. Responses to the six items are subsequently added up, resulting in a scale ranging from 6–30. The higher total score reflects a higher level of addictive social media use. A score of 19 or greater has been identified as a cut-point for significant social media addiction (Bányai et al., 2017). This cut-point means that the participant has responded “sometimes” to at least five of the items + at least “often” to one item; or “often” to at least four items and “rarely” to at least one item; or “very often” to at least three items and “rarely” to at least one item. A categorical variable was created to distinguish different groups, i.e., 1 = no symptoms of social media addiction, i.e., the lowest score of 6 (REF category); 2 = symptoms below cut-point, i.e., scores from 7 to 18; and 3 = social media addiction (above cut-point, score ≥19).

Outcome 1: Depression

The eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-8) was used to screen for depression symptoms (Kroenke et al., 2009). The total scale ranges from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating more depression symptoms. A cut-point of ≥10 for depression was used (Kroenke et al., 2009). The binary outcome variable, i.e., case depression, came from the 2021 survey.

Outcome 2: Mental Wellbeing

The Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS) was used to assess mental wellbeing (Koushede et al., 2019). Summing item scores leads to a score between 7 and 35; the higher the score, the higher mental wellbeing. For the descriptive analysis only, cut-points for low, moderate, and high mental wellbeing were used (Santini et al., 2022). The continuous outcome variable, i.e., mental wellbeing, came from the 2021 survey.

Outcome 3: Loneliness (Relating to Perceived Isolation)

The short form of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale was used to assess loneliness (Hughes et al., 2004; Russell et al., 1980). Scores are summed to create a total score that runs from 3 to 9, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of loneliness. In accordance to previous literature, a score of 7 or greater was used as a cut-point for loneliness (Boehlen et al., 2015). The binary outcome variable, i.e., loneliness, came from the 2021 survey.

Outcome 4: Social Network Size (Relating to Objective Isolation)

With regard to social network size, participants were asked “How many persons are so close to you, that you can count on them, if you have serious personal problems?”. This item was taken from the Oslo Social Support Scale (OSS-3) (Kocalevent et al., 2018). Response options were (1) none, (2) 1–2 persons, (3) 3–5 persons, and (4) 6 persons or more. Responses were transformed into a numerical scale by taking the average in each response option and then rounding up to the nearest whole number, resulting in a variable with 0, 2, 4, and 6 persons, respectively. The continuous variable, i.e., social network size, came from the 2021 survey.

Covariates

The choice of covariates was based on prior research on social media addiction and mental health (e.g., Dailey et al., 2020; Shensa et al., 2017) and included demographic and socioeconomic variables. The sociodemographic variables were as follows: age (continuous, categorical for descriptives analysis), sex (female, male), country of origin (Denmark, other), marital status (never married or in a registered partnership, married or registered partnership, divorced or widowed), household size (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or more persons living in the household), education (primary/10th grade, high school or vocational, tertiary education), household income (lowest quartile, second-lowest quartile, second-highest quartile, highest quartile), and occupation (employed, student).

Data on occupation came from the baseline survey (2020), while data on sex, age, marital status, education, household income, household size, and country of origin were obtained from the Civil Registration System (Pedersen, 2011; Thygesen et al., 2011).

Statistical Analysis

STATA version 16 was used to perform all analyses. First, a descriptive analysis was conducted to demonstrate the characteristics of the sample, as well as BSMAS mean and standard deviations (SD) by group. These analyses included frequencies, proportions, means, standard deviations (SD), and oneway ANOVAs. For the descriptive analysis only, age and mental wellbeing were converted to categorical variables. Next, multivariable logistic or linear regression was conducted to assess the associations between BSMAS and the outcome variables. As stated above, BSMAS (exposure variable, continuous and binary) was based on data collected at baseline (2020), with the four outcomes of depression (binary - logistic), mental wellbeing (continuous - linear), loneliness (binary - logistic), and social network size (continuous - linear) having been collected in 2021. The analyses pertaining to the binary outcomes of depression and loneliness in 2021 were conducted among those without the respective outcome at baseline in 2020, and this assessed risk for new cases of depression and loneliness, respectively. Thus, those with the respective outcome at baseline were omitted from the logistic regression analyses. The analyses pertaining to the continuous outcomes of mental wellbeing and social network size in 2021 were conducted on the whole sample and were adjusted for the respective outcome at baseline, i.e., mental wellbeing in 2020 and social network size in 2020, respectively. In order to investigate whether sex moderated the relationship between BSMAS and the outcomes, we also ran models with the product terms BSMAS x sex (binary). Further, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess associations between BSMAS scores at baseline in 2020 and single depression, mental wellbeing, and loneliness items in 2021. This was conducted in order to assess if some outcome items in the depression, mental wellbeing, and loneliness scales were particularly sensitive to social media addiction symptoms and driving associations. To do this, multivariate regression models for assessing associations with multiple outcomes were conducted using the Stata mvreg command. The multivariate regression models for each scale were adjusted for all individual baseline items. Finally, in order to investigate bi-directionality, we conducted linear regression models with the outcomes and predictor reversed, i.e., mental health and social isolation predictors (depression, mental wellbeing, loneliness, network size) in 2020 predicting social media addiction symptoms in 2021 (adjusting for covariates including social media addiction symptoms at baseline).

Results

Information regarding the socioeconomic distribution of the study samples is shown in Table 1, including n (%) for missing data. The mean age of the study sample was 45.6 years, and 61.8% were females. Histograms showed right skewed distributions for social media addiction symptoms (mean = 9.4, SD = 3.7), depression (mean = 3.4, SD = 4.1), and loneliness (mean = 4.1, SD = 1.5), a normal distribution for mental wellbeing (mean = 24.8, SD = 4.4), and a left skewed distribution for network size (mean = 4.5, SD = 1.5). A tendency for higher BSMAS scores was observed for lower age groups, females, and students. A clear social gradient was indicated with higher BSMAS scores observed for lower education, lower household income, and among unmarried individuals. In all, 44 individuals (2.3%) screened positive for social media addiction (BSMAS score of ≥19). In 2021, there were 156 (9.4%) new cases of depression and 57 (3.7%) new cases of loneliness (results not shown in tables).

Regarding the analytical models, a consistent pattern was seen across all outcomes, where increased social media addiction symptoms were associated with significantly increased risk. In terms of the logistic regression on depression (Table 2), the results show that the continuous BSMAS scale at baseline was positively associated with depression (OR=1.06, 95% CI 1.01–1.11) at follow-up. In terms of the binary BSMAS variable, as compared to the group with no symptoms, those screening positive for social media addiction had an OR of 2.71 (95% CI 1.08, 6.83) for developing depression. The group with symptoms below the cut-point did not reach statistical significance in the association with depression.

As for the linear regression on mental wellbeing (Table 2), the continuous BSMAS scale at baseline was inversely associated with mental wellbeing (coef = −0.06, 95% CI −0.11, −0.02) at follow-up. In terms of the binary BSMAS variable, as compared to the group with no symptoms, those screening positive for social media addiction had a coefficient of −1.29 (95% CI −2.41, −0.16) with mental wellbeing. The group with symptoms below the cut-point did not reach statistical significance in the association with mental wellbeing.

In terms of the logistic regression on loneliness (Table 3), the results show that the continuous BSMAS scale at baseline was positively associated with loneliness (OR=1.14, 95% CI 1.07–1.22) at follow-up. In terms of the binary BSMAS variable, as compared to the group with no symptoms, those screening positive for social media addiction had an OR of 4.40 (95% CI 1.20, 16.19) for becoming lonely. The group with symptoms below the cut-point did not reach statistical significance in the association with loneliness.

As for the linear regression on social network size (Table 3), the continuous BSMAS scale at baseline was inversely associated with social network size (coef = −0.03, 95% CI −0.05, −0.01) at follow-up. In terms of the binary BSMAS variable, as compared to the group with no symptoms, those screening positive for social media addiction had a coefficient of −0.46 (95% CI −0.86, −0.06) with social network size. The group with symptoms below the cut-point did not reach statistical significance in the association with social network size.

With regard to the moderation analysis on potential sex differences in the association between BSMAS and the outcomes, we did not find evidence of any significant interaction terms (p-value range = 0.315–0.995; results not shown in tables). With regard to the sensitivity analysis (Table A1 in the appendix), this showed that some individual items were more significantly associated (i.e., based on statistical significance and confidence intervals) with social media addiction symptoms and were primarily driving the association between the exposure and the outcomes. Significant items were grouped into six domains, as follows: (1) cognitive deficits, (2) inhibited resilience, (3) feelings of tension, (4) social disconnectedness, (5) depressed mood and fatigue, and (6) compromised self-esteem. Finally, with regard to bi-directional relationships, Table A2 in the appendix shows the models with outcomes and predictor reversed, i.e., mental health and social isolation variables (depression, mental wellbeing, loneliness, network size) in 2020 predicting social media addiction symptoms in 2021. These results show that depression symptoms and loneliness at baseline positively predicted social media addiction symptoms at follow-up, while mental wellbeing negatively predicted social media addiction symptoms. Network size did not significantly predict social media addiction symptoms.

Discussion

Using a population-based longitudinal survey comprising a large sample of Danish adults (16–64 years old) in education or employment, we set out to investigate prospective associations between social media addiction symptoms at baseline (2020) and the outcomes one year later (2021). Supporting our first hypothesis, we found that each increase in social media addiction symptoms was significantly predictive of all outcomes, i.e., positively predictive of depression and loneliness and negatively predictive of mental wellbeing and social network size (the number of close social ties). Supporting our second hypothesis, we found that compared to those with no symptoms, social media addiction was associated with an elevated risk of depression (about two-fold and a half) and was inversely associated with mental wellbeing, Similarly, social media addiction was also associated with an elevated risk of loneliness (about four-fold and a half) and was inversely associated with social network size. The estimates for social media addiction symptoms below the cut-point (BSMAS score 7–18) also indicated elevated risk but did not reach statistical significance. Finally, our analysis also showed bi-directional associations, i.e., compromised mental health and loneliness in 2020 were positive predictors of social media addiction symptoms in 2021.

Strengths and Limitations

Some strengths and limitations should be noted when interpreting the results. Major strengths include the use of data from a large nationwide survey, the prospective design (including the adjustment for confounders), the use of a validated scale for measuring mental wellbeing, and the link with national administrative registers (as a means to obtain relevant demographic and socioeconomic data on participants). Some limitations are as follows: First, the response rate at baseline was 47.4%, and while this is relatively high for a web-based/paper-based survey, non-response bias cannot be ruled out. In terms of the longitudinal survey-based analyses, the proportion of baseline participants who took part in the follow-up survey was relatively high (80.2%), but there is a possibility for attrition bias in this part of the study. Second, the survey data available to us made it possible to assess a number of outcomes pertaining to mental health problems and social isolation; however, we did not have sufficient or adequate survey data on potentially relevant substance use outcomes. Hence, we were, in this study, not able to investigate associations between the predictor and such outcomes. Third, it may be noted that the survey took place in 2020–2021, which was during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Danish government initiated a lockdown of society on the 11th of March 2020 and later initiated a gradual reopening of society on the 17th of April 2020. Another lockdown was initiated again on the 16th of December 2020, which lasted until the 1st of March 2021. Our study documented associations between social media addiction symptoms in the 2020 pandemic year and the outcomes in the following year. We cannot exclude the possibility that the associations would differ to some extent if the assessment of social media addiction symptoms and the outcomes had taken place in times without a pandemic. That said, we had access to 2019 data (pre-pandemic EHIS data) and were able to test the mean difference in BSMAS scores from 2019 to 2020, and we observed no significant increase in BSMAS scores from before the pandemic to the pandemic year (p=0.27, results not shown).

Contextualization and Implications for Policy and Practice

A total of 2.3% of the people in our sample screened positive for social media addiction. To relate this number to other behavioral addictions, this may be compared to 10.9% of the Danish population showing signs of mild pathological gambling disorder and 0.7% showing signs of severe pathological gambling disorder (Ramböll., 2022); or to 2–3% suffering from Binge Eating Disorder (BED) (Sundhedsstyrelsen, 2022). Our analytical results align with most previous studies showing positive associations between social media addiction symptoms and mental health (Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2017; Chen et al., 2020; Muusses et al., 2014; Raudsepp, 2019; Raudsepp & Kais, 2019; Vernon et al., 2017) or perceived and objective isolation (Marttila et al., 2021; Muusses et al., 2014). The results that do not appear to align with previous findings are likely accounted for by short follow-up periods in previous studies (Di Blasi et al., 2022) or due to the fact that previous studies used different wellbeing (life satisfaction) (Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2017; Marttila et al., 2021) or social (support) (Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2017) construct measures than those used in the current study, which may not be as sensitive to social media addiction symptoms. Using longitudinal data from a large nationwide survey representative of Danish adults in education or employment, our estimates suggest that social media addiction—symptoms and above cut-point—significantly predicts all outcomes. The study findings lend support to existing etiological models of dual diagnosis (Moggi, 2005), primarily direct models (i.e., social media addiction leading to depression) and bi-directional models (compromised mental health leading to social media addiction), and are perhaps also indicative of indirect models (e.g., social media addiction leading to loneliness and loss of social relationships, in turn leading to depression).

Our sensitivity analysis indicates that some outcome items may be more significantly impacted by social media addiction symptoms than others. The significant items share some similar features and were grouped into six domains, as follows (not in order of occurrence or development): (1) cognitive deficits, (2) inhibited resilience, (3) feelings of tension, (4) social disconnectedness, (5) depressed mood and fatigue, and (6) compromised self-esteem. These domains fit with well-known psycho-social consequences of addiction (Griffiths, 2005; Griffiths et al., 2014; Kuss & Griffiths, 2011). For example, preoccupation or obsession with the addictive behavior may lead to cognitive deficits (e.g., being unable to concentrate on other things) or inhibited resilience (e.g., diminished ability to handle normal challenges or stressors). Feelings of tension of discomfort may occur as a results of recurring cycles of withdrawal (when unable to engage in the addictive behavior due to being at work or because of other obligations). Social disconnectedness may occur, for example, due to the addictive behavior taking precedence over social relationships or due to social withdrawal or reduced social appeal. Ultimately, the addictive behavior may lead to a depressed mood as the addictive behavior becomes less satisfying or requires a higher dose to produce a high (due to tolerance); or lead to fatigue due to having to repeatedly engage in continuous cycles of engaging in the addictive behavior in order to satisfy cravings. It may also lead to compromised self-esteem, due to regretting behaviors resulting from the addiction or due to failed attempts to limit or reduce the behavior. Naturally, this is not an exhaustive list of mechanisms between social media addiction and the outcomes; rather, these are examples of common psycho-social consequences of addictions in general. The point is that our findings support the view that social media addiction does not only share core components of addiction, but that the consequences of social media addiction symptoms may be devastating and appear to be shared with those commonly reported in the context of recognized clinical addiction disorders. In light of related clinical disorders such as internet addiction in China (Jiang, 2022) and gaming disorder in the ICD-11 (Billieux et al., 2021; Castro-Calvo et al., 2021), both officially established as clinical diagnoses since 2018, our findings suggest that social media addiction may have equal or similar clinical relevance, as it shares common core features as well as posing significant risk to mental health and social functioning. This also emphasizes the need for a greater understanding and recognition in both clinical and public discourse that addictive social media use is not without risks or harms.

It is necessary to prevent social media addiction in the general working age population, of which the overwhelming majority uses social media on a daily basis. Contrary to many other addictive substances that are not as readily available and accessible (e.g., alcohol, drugs and food must be bought; gambling requires money), social media is generally free to use, ever present, and within reach through one’s smartphones and laptop. This presents social media addiction as a potentially greater risk of exposure to a larger number of people in a population, relative to other substances or potentially addictive behaviors. This is not to imply that social media addiction is more harmful to mental health and social relationships than substance use and other behavioral addictions, but rather that the potential for developing social media addiction possibly applies to a greater number of people in a population due to the availability and accessibility of social media. There are several avenues for preventative policies, such as ensuring greater data transparency and safer non-addictive algorithms on social media platforms (Raffoul et al., 2023), limiting screen time among youth in particular (Devi & Singh, 2023), as well as mental health promotion and awareness raising about mentally healthy behaviors as opposed to addictive behaviors (Santini et al., 2017; Santini, Meilstrup, et al., 2020). Future research is warranted to investigate a number of things that we were not able to investigate as part of the current study, including (1) whether advanced network analysis techniques (Borsboom, 2017; Borsboom & Cramer, 2013) could offer a more comprehensive perspective on the intricate relationships between social media addiction symptoms and mental health, for example, by the utilization of structural equation modeling (SEM) in longitudinal designs to elucidate the temporal dynamics between core predictor and outcome symptoms; (2) whether different types of social media addictions exist (e.g., addictive self-promotion focused social media use vs addictive but passive social media profile following and resharing posts) (Kuss & Griffiths, 2011); (3) whether the associations between social media addiction symptoms and the outcomes are moderated by social media platform preference or motivation for social media use (Brailovskaia et al., 2020; Sheldon et al., 2011; Stockdale & Coyne, 2020); and (4) whether differential predictors of different types of social media addiction exist (Griffiths et al., 2014; Lim et al., 2020; Sheldon et al., 2020).

Conclusion

Using a large nationwide survey representative of Danish adults (16–64 years old) in education or employment, we set out to document associations between social media addiction symptoms (using the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale; BSMAS) in 2020 and mental health as well as social isolation outcomes in 2021. After adjustment, we found that overall BSMAS score (continuous measure) at baseline was significantly predictive of all outcomes at follow-up. Overall, 2.3% screened positive for social media addiction (BSMAS score ≥19). Compared to those with no symptoms, social media addiction was associated with an elevated risk of depression (about two-fold and a half) and was inversely associated with mental wellbeing. Similarly, social media addiction was associated with an elevated risk of loneliness (about four-fold and a half) and was inversely associated with social network size (the number of close social ties). There is a need for preventive actions against addictive social media use, as this poses significant risk to mental health and social functioning in the working age population.

Data Availability

We do not have permission to share data.

References

Aladwani, A. M., & Almarzouq, M. (2016). Understanding compulsive social media use: The premise of complementing self-conceptions mismatch with technology. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 575–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.098

Andreassen, C. S., Pallesen, S., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006

Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.09.18.Pr0.110.2.501-517

Bányai, F., Zsila, Á., Király, O., Maraz, A., Elekes, Z., Griffiths, M. D., Andreassen, C. S., & Demetrovics, Z. (2017). Problematic social media use: Results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS One, 12(1), e0169839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169839

Bharne, S., & Bhaladhare, P. (2023). Comprehensive Analysis of Online Social Network Frauds. Advances in Data-Driven Computing and Intelligent Systems. Singapore, Springer Nature Singapore, (pp. 23–40)

Billieux, J., Stein, D. J., Castro-Calvo, J., Higushi, S., & King, D. L. (2021). Rationale for and usefulness of the inclusion of gaming disorder in the ICD-11. World Psychiatry, 20(2), 198–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20848

Boehlen, F., Herzog, W., Quinzler, R., Haefeli, W. E., Maatouk, I., Niehoff, D., Saum, K.-U., Brenner, H., & Wild, B. (2015). Loneliness in the elderly is associated with the use of psychotropic drugs. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(9), 957–964. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4246

Borsboom, D. (2017). A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20375

Borsboom, D., & Cramer, A. O. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 91–121.

Brailovskaia, J., & Margraf, J. (2017). Facebook Addiction Disorder (FAD) among German students—A longitudinal approach. PLoS One, 12(12), e0189719. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189719

Brailovskaia, J., Schillack, H., & Margraf, J. (2020). Tell me why are you using social media (SM)! Relationship between reasons for use of SM, SM flow, daily stress, depression, anxiety, and addictive SM use–An exploratory investigation of young adults in Germany. Computers in Human Behavior, 113, 106511.

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2010). Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 453–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017216

Castro-Calvo, J., King, D. L., Stein, D. J., Brand, M., Carmi, L., Chamberlain, S. R., Demetrovics, Z., Fineberg, N. A., Rumpf, H.-J., Yücel, M., Achab, S., Ambekar, A., Bahar, N., Blaszczynski, A., Bowden-Jones, H., Carbonell, X., Chan, E. M. L., Ko, C.-H., de Timary, P., et al. (2021). Expert appraisal of criteria for assessing gaming disorder: An international Delphi study. Addiction, 116(9), 2463–2475. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15411

Charlson, F. J., Baxter, A. J., Dua, T., Degenhardt, L., Whiteford, H. A., & Vos, T. (2016). Excess mortality from mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in the global burden of disease study 2010.

Chen, I. H., Pakpour, A. H., Leung, H., Potenza, M. N., Su, J. A., Lin, C. Y., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Comparing generalized and specific problematic smartphone/internet use: Longitudinal relationships between smartphone application-based addiction and social media addiction and psychological distress. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(2), 410–419. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00023

Dailey, S. L., Howard, K., Roming, S. M. P., Ceballos, N., & Grimes, T. (2020). A biopsychosocial approach to understanding social media addiction. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(2), 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.182

Devi, K. A., & Singh, S. K. (2023). The hazards of excessive screen time: Impacts on physical health, mental health, and overall well-being. Journal of Education Health Promotion, 12(1) https://journals.lww.com/jehp/fulltext/2023/11270/the_hazards_of_excessive_screen_time__impacts_on.413.aspx

Di Blasi, M., Salerno, L., Albano, G., Caci, B., Esposito, G., Salcuni, S., Gelo, O. C. G., Mazzeschi, C., Merenda, A., Giordano, C., & Lo Coco, G. (2022). A three-wave panel study on longitudinal relations between problematic social media use and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addictive Behaviors, 134, 107430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107430

Fournier, L., Schimmenti, A., Musetti, A., Boursier, V., Flayelle, M., Cataldo, I., Starcevic, V., & Billieux, J. (2023). Deconstructing the components model of addiction: An illustration through “addictive” use of social media. Addictive Behaviors, 143, 107694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107694

GBD. (2022). Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(2), 137–150.

Girault, C., Schramm, S., Tolstrup, J. S., Ekholm, O., & Bramming, M. (2023). Changes in loneliness prevalence in Denmark in the 21st century: Age-period-cohort analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 14034948231182188. https://doi.org/10.1177/14034948231182188

Griffiths, M. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359

Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Chapter 6 - social networking addiction: An overview of preliminary findings. In K. P. Rosenberg & L. C. Feder (Eds.), Behavioral Addictions (pp. 119-141). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407724-9.00006-9

Grubb, J. A. (2020). The rise of sex trafficking online. The Palgrave handbook of international cybercrime and cyberdeviance, pp. 1151–1175.

Helliwell, J., Wang, S., Huang, H., & Norton, M. (2022). Happiness, benevolence, and trust during COVID-19 and beyond. World Happiness Report.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

Huang, C. (2022). A meta-analysis of the problematic social media use and mental health. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 68(1), 12–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020978434

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672.

Jeppesen, P., Obel, C., Lund, L., Madsen, K. B., Nielsen, L., & Nordentoft, M. (2020). Mental sundhed og sygdom hos børn og unge i alderen 10-24 år - forekomst, udvikling og forebyggelsesmuligheder. Vidensråd for Forebyggelse.

Jiang, Q. (2022). Development and effects of internet addiction in China. Oxford University Press.

Kocalevent, R.-D., Berg, L., Beutel, M. E., Hinz, A., Zenger, M., Härter, M., Nater, U., & Brähler, E. (2018). Social support in the general population: Standardization of the Oslo social support scale (OSSS-3). BMC Psychology, 6(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0249-9

Koushede, V., Lasgaard, M., Hinrichsen, C., Meilstrup, C., Nielsen, L., Rayce, S. B., Torres-Sahli, M., Gudmundsdottir, D. G., Stewart-Brown, S., & Santini, Z. I. (2019). Measuring mental well-being in Denmark: Validation of the original and short version of Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS and SWEMWBS) and cross-cultural comparison across four European settings. Psychiatry Research, 271, 502–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.003

Kroenke, K., Strine, T. W., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Berry, J. T., & Mokdad, A. H. (2009). The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 114(1), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2011). Online social networking and addiction—A review of the psychological literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(9), 3528–3552 https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/8/9/3528

Lim, M., Cheung, F. Y.-L., Kho, J. M., & Tang, C.-K. (2020). Childhood adversity and behavioural addictions: The mediating role of emotion dysregulation and depression in an adult community sample. Addiction Research & Theory, 28(2), 116–123.

Marttila, E., Koivula, A., & Räsänen, P. (2021). Does excessive social media use decrease subjective well-being? A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between problematic use, loneliness and life satisfaction. Telematics and Informatics, 59, 101556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101556

Moggi, F. (2005). Etiological theories on the relationship of mental disorders and substance use disorders. Bibliotheca Psychiatrica, 172, 1–14.

Muusses, L. D., Finkenauer, C., Kerkhof, P., & Billedo, C. J. (2014). A longitudinal study of the association between Compulsive Internet use and wellbeing. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.035

Ortiz-Ospina, E. (2019). The rise of social media. Retrieved 12-27-2023, from https://ourworldindata.org/rise-of-social-media

Pedersen, C. B. (2011). The Danish Civil Registration System. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39(7 Suppl), 22–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810387965

Plana-Ripoll, O., Pedersen, C. B., Agerbo, E., Holtz, Y., Erlangsen, A., Canudas-Romo, V., Andersen, P. K., Charlson, F. J., Christensen, M. K., Erskine, H. E., Ferrari, A. J., Iburg, K. M., Momen, N., Mortensen, P. B., Nordentoft, M., Santomauro, D. F., Scott, J. G., Whiteford, H. A., Weye, N., et al. (2019). A comprehensive analysis of mortality-related health metrics associated with mental disorders: A nationwide, register-based cohort study. The Lancet, 394(10211), 1827–1835. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32316-5

Prince, M., Patel, V., Saxena, S., Maj, M., Maselko, J., Phillips, M. R., & Rahman, A. (2007). No health without mental health. Lancet, 370(9590), 859–877. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61238-0

Raffoul, A., Ward, Z. J., Santoso, M., Kavanaugh, J. R., & Austin, S. B. (2023). Social media platforms generate billions of dollars in revenue from U.S. youth: Findings from a simulated revenue model. PLoS One, 18(12), e0295337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295337

Ramböll. (2022). Prævalensundersøgelse af pengespil og pengespilsproblemer i danmark 2021. Ramböll.

Raudsepp, L. (2019). Brief report: Problematic social media use and sleep disturbances are longitudinally associated with depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 76, 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.09.005

Raudsepp, L., & Kais, K. (2019). Longitudinal associations between problematic social media use and depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Preventive Medicine Reports, 15, 100925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100925

Rehm, J., & Shield, K. D. (2019). Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-0997-0

Rosendahl Jensen, H. A., Thygesen, L. C., Møller, S. P., Dahl Nielsen, M. B., Ersbøll, A. K., & Ekholm, O. (2021). The Danish Health and Wellbeing Survey: Study design, response proportion and respondent characteristics. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 14034948211022429. https://doi.org/10.1177/14034948211022429

Rosendahl Jensen, H. A., Thygesen, L. C., Møller, S. P., Dahl Nielsen, M. B., Ersbøll, A. K., & Ekholm, O. (2022). The Danish Health and Wellbeing Survey: Study design, response proportion and respondent characteristics. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 50(7), 959–967. https://doi.org/10.1177/14034948211022429

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

Santini, Z. I., Ekholm, O., Koyanagi, A., Stewart-Brown, S., Meilstrup, C., Nielsen, L., Fusar-Poli, P., Koushede, V., & Thygesen, L. C. (2022). Higher levels of mental wellbeing predict lower risk of common mental disorders in the Danish general population. Mental Health & Prevention, 26, 200233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2022.200233

Santini, Z. I., Jose, P. E., York Cornwell, E., Koyanagi, A., Nielsen, L., Hinrichsen, C., Meilstrup, C., Madsen, K. R., & Koushede, V. (2020). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans: A longitudinal mediation analysis of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP). The Lancet Public Health, 5, e62–e70.

Santini, Z. I., Meilstrup, C., Hinrichsen, C., Nielsen, L., Koyanagi, A., Koushede, V., Ekholm, O., & Madsen, K. R. (2020). Associations between multiple leisure activities, mental health and substance use among adolescents in Denmark: A nationwide cross-sectional study [original research]. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 14(232). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2020.593340

Santini, Z. I., Nielsen, L., Hinrichsen, C., Nelausen, M. K., Meilstrup, C., Koyanagi, A., McDaid, D., Lyubomirsky, S., VanderWeele, T. J., & Koushede, V. (2021). Mental health economics: A prospective study on psychological flourishing and associations with healthcare costs and sickness benefit transfers in Denmark. Mental Health & Prevention, 24, 200222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2021.200222

Santini, Z. I., Nielsen, L., Hinrichsen, C., Tolstrup, J. S., Vinther, J. L., Koyanagi, A., Donovan, R. J., & Koushede, V. (2017). The association between Act-Belong-Commit indicators and problem drinking among older Irish adults: Findings from a prospective analysis of the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 180, 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.08.033

Sheldon, K. M., Abad, N., & Hinsch, C. (2011). A two-process view of Facebook use and relatedness need-satisfaction: Disconnection drives use, and connection rewards it. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(4), 766–775. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022407

Sheldon, P., Antony, M. G., & Sykes, B. (2020). Predictors of problematic social media use: Personality and life-position indicators. Psychological Reports, 124(3), 1110–1133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294120934706

Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Sidani, J. E., Bowman, N. D., Marshal, M. P., & Primack, B. A. (2017). Problematic social media use and depressive symptoms among U.S. young adults: A nationally-representative study. Social Science & Medicine, 182, 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.061

SST. (2022). Danskernes Sundhed – Den Nationale Sundhedsprofil 2021. Sundhedsstyrelsen.

Stockdale, L. A., & Coyne, S. M. (2020). Bored and online: Reasons for using social media, problematic social networking site use, and behavioral outcomes across the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence, 79, 173–183.

Sundhedsstyrelsen. (2022). Indsatsen over for tvangsoverspisning styrkes. Retrieved 01-01 from https://www.sst.dk/da/nyheder/2022/indsatsen-over-for-tvangsoverspisning-styrkes

Surkalim, D. L., Luo, M., Eres, R., Gebel, K., Buskirk, J. V., Bauman, A., & Ding, D. (2022). The prevalence of loneliness across 113 countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj, 376, e067068. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-067068

Thygesen, L. C., Daasnes, C., Thaulow, I., & Brønnum-Hansen, H. (2011). Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: Structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39(7_suppl), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494811399956

van den Eijnden, R., Koning, I., Doornwaard, S., van Gurp, F., & Ter Bogt, T. (2018). The impact of heavy and disordered use of games and social media on adolescents’ psychological, social, and school functioning. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(3), 697–706. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.65

Verduyn, P., Ybarra, O., Résibois, M., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2017). Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11(1), 274–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12033

Vernon, L., Modecki, K. L., & Barber, B. L. (2017). Tracking effects of problematic social networking on adolescent psychopathology: The mediating role of sleep disruptions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(2), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1188702

WHO. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. World Health Organization.

Zarate, D., Hobson, B. A., March, E., Griffiths, M. D., & Stavropoulos, V. (2023). Psychometric properties of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale: An analysis using item response theory. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 17, 100473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2022.100473

Zsila, Á., & Reyes, M. E. S. (2023). Pros & cons: Impacts of social media on mental health. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 201. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01243-x

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Southern Denmark. Velliv Foreningen (grant number 20-0438).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed to the work submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study is a secondary data analysis with no human subject issues. Ethics statement is included in the paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Transparency Declaration

The manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported. No important aspects of the study have been omitted. Any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary file 1

(PDF 175 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Santini, Z.I., Thygesen, L.C., Andersen, S. et al. Social Media Addiction Predicts Compromised Mental Health as well as Perceived and Objective Social Isolation in Denmark: A Longitudinal Analysis of a Nationwide Survey Linked to Register Data. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01283-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01283-3