Abstract

Although low-dose direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are recommended for patients at high risk of bleeding complications, it remains unclear whether the dose reduction in real-world setting is also appropriate in patients after large-vessel occlusion (LVO) stroke. This study hypothesized that patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and LVO receiving low-dose DOACs have an increased risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic events. The study aimed to assess 1 year morbidity and mortality in patients treated with standard-dose and low-dose apixaban after LVO stroke. A post hoc analysis was performed using the acute LVO registry data, which enrolled patients with AF and LVO who received apixaban within 14 days of stroke onset. The incidences of ischemic events (ischemic stroke, acute coronary syndrome, acute myocardial infarction, and systemic embolism), major bleeding events, and death from any cause were compared between patients receiving standard- and low-dose apixaban. Of 643 patients diagnosed with LVO, 307 (47.7%) received low-dose apixaban. After adjustment for clinically relevant variables, no significant differences were observed in the incidence of ischemic events (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]: 2.12, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.75–6.02), major bleeding events (aHR: 1.17, 95% CI 0.50–2.73), and death from any cause (aHR: 1.95, 95% CI 0.78–4.89) between patients receiving standard- and low-dose apixaban. No significant differences were observed in the incidence of ischemic events, major bleeding events, or death from any cause between patients with AF and LVO receiving standard- and low-dose apixaban.

Similar content being viewed by others

Highlights

-

It is unclear whether the dose reduction in real-world setting is appropriate in patients after large-vessel occlusion (LVO) stroke.

-

This study showed that the risk of ischemic/bleeding events or mortality is not significantly increased in patients receiving low-dose apixaban after LVO stroke compared with those receiving standard-dose apixaban.

-

It is probable that the background factors, rather than the apixaban dose, were probably responsible for the differences in mortality outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation and LVO.

-

Studies targeting other DOACs should be considered because each DOAC has different criteria for dose adjustment.

Introduction

Apixaban, a direct Factor Xa inhibitor, was reported to be effective and safe for preventing stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) compared with warfarin in a large randomized clinical trial (ARISTOTLE) [1]. The standard dose of apixaban is 5 mg twice daily. However, it is recommended that the dose be reduced to 2.5 mg twice daily in patients at high risk of bleeding complications who meet at least two of the following three criteria: (i) age ≥ 80 years, (ii) weight ≤ 60 kg, and (iii) serum creatinine ≥ 1.5 mg/dL. In the ARISTOTLE study, only 4.7% of patients received low-dose apixaban [1]; while 30–63% of patients received low-dose apixaban in recent real-world observational studies [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. However, several studies have reported a higher incidence of cardiovascular events and mortality in patients receiving low-dose apixaban than in those receiving standard-dose apixaban although these results were attributed to background factors such as age [2,3,4,5].

On the other hand, a previous study showed that patients with AF and a large ischemic stroke had an increased risk of recurrent stroke and major bleeding compared with those with a small ischemic stroke [9]. One possible reason is that the current dose adjustment for direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in real-world clinical setting may be inappropriate for patients at high risk of recurrent stroke such as patients with large ischemic stroke or large-vessel occlusion (LVO). Therefore, this study hypothesized that patients receiving low-dose DOACs would have an increased risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic events in patients after LVO stroke, even after adjusting for background factors. This study aimed to assess the 1 year morbidity and mortality by comparing the incidence of ischemic events (ischemic stroke, acute coronary syndrome, acute myocardial infarction, and systemic embolism), major hemorrhagic events, and death from any cause of patients receiving standard- and low-dose apixaban in a large Japanese registry of patients with acute cardioembolic stroke and LVO.

Methods

Participants and data collection

This study was a post hoc analysis of the Apixaban on clinical outcome of the patients with large vessel occlusion or stenosis (ALVO) study. The inclusion criteria of ALVO study were patients aged at least 20 years, with acute ischemic stroke with LVO or intra-/extra-cranial artery stenosis and AF, and received apixaban within 14 days after the onset [10]. The definition of AF in ALVO trial did not include patients with mechanical valves or moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis, who were ineligible for the use of DOACs. In principle, apixaban was administered according to medical package insert in Japan, and low-dose apixaban was used for patients with at least two of the following three criteria: (i) age ≥ 80 years, (ii) weight ≤ 60 kg, and (iii) serum creatinine ≥ 1.5 mg/dL; however, the actual dosage was selected by the treating physicians. The exclusion criteria were patients who are considered ineligible for the study by the investigator, pregnant or potentially pregnant, with a history of hypersensitivity to apixaban, with liver disease with coagulopathy and clinically significant bleeding risk, with renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance < 15 mL/min) and with pathological bleeding including intracranial bleeding of any type [10]. Clinical information was collected by reviewing medical records. Follow-up information was collected at 30, 90, and 365 days of stroke onset, and any additional information was obtained by contacting the patients, relatives, and referring physicians.

This study excluded patients with stenosis without LVO. LVO defined as (i) M1—3 segment middle cerebral artery occlusion, (ii) A1—2 segment anterior cerebral artery occlusion, (iii) P1—2 segment posterior cerebral artery occlusion, (iv) internal carotid artery occlusion, (v) basilar artery occlusion, or (vi) vertebral artery occlusion were included. The following baseline data were used in the analyses: age, sex, underlying disease (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic heart failure, a history of ischemic stroke, cerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and coronary artery disease), post-stroke CHD2DS2-VASc score [11], pre-stroke modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score [12], antithrombotic medication at stroke onset, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score [13], serum creatinine, blood glucose and HbA1c on admission, occlusion site, use of intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (IV rt-PA; 0.6 mg/kg), endovascular therapy (EVT) using any device approved in Japan, and modified thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (mTICI) score for patients with EVT [14]. The body weight data were not collected in the ALVO study, which primarily planned to confirm the safety of early administration of apixaban. The presence of intracranial hemorrhage prior to apixaban administration was also evaluated using the Heidelberg Bleeding Classification [15].

Study end points

Ischemic events, major bleeding events, and death from any cause were assessed within 365 days of apixaban administration. The ischemic events included ischemic stroke, acute coronary syndrome, acute myocardial infarction, and systemic embolism. Major bleeding events were defined as any bleeding event according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis major bleeding [16].

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics and outcomes were compared between those who received standard-dose apixaban (5 mg twice daily) and those who received low-dose apixaban (2.5 mg twice daily). Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test based on the distributions. Fisher’s exact or chi-squared tests were used for categorical variables when appropriate. The cumulative incidences of ischemic events, major bleeding events, and death from any cause were analyzed. The starting point of the follow-up study was the time of apixaban administration. Patients were censored at the time of ischemic events, major bleeding events, or death within 365 days of index stroke onset.

Univariate Cox regression models were developed to analyze the associations between baseline variables and outcomes. Multivariate Cox regression models were developed to assess the independent association between the apixaban dose and outcome, adjusting for the following clinically relevant variables: age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic heart failure, history of ischemic stroke, prior antiplatelet therapy, serum creatinine level, IV rt-PA, and EVT. To assess the heterogeneity of the association between apixaban dose and outcome by baseline characteristics, subgroup analyses based on sex, age (≥ 80 or < 80), with or without IV rt-PA, and with or without EVT were performed. The interactions were tested using a multiplicative interaction term (each outcome × variable) included in the models.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to validate the results. Multivariate stepwise Cox regression models were developed to reduce the number of confounders; these models included parameters associated with each outcome in the univariate analysis (p < 0.05). All statistical analyses were performed using EZR version 1.55 (Saitama Medical Centre, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan) [17], a graphical user interface for R (version 4.1.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All reported p-values were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

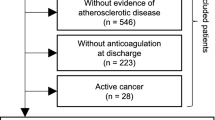

Of the 713 registry participants, 27 were excluded from the primary multicenter study. Patients without LVO were excluded (n = 43), and 643 patients were enrolled in the present study (Fig. 1). Standard- and low-dose apixaban were prescribed to 336 and 307 patients, respectively. The median follow-up period was 364 (IQR: 347–365) days for patients on standard-dose apixaban and 358 (IQR: 170–365) days for patients on low-dose apixaban (p < 0.001). The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Compared to patients on standard-dose apixaban, those on low-dose apixaban were significantly older (71.5 ± 8.5 vs. 83.6 ± 6.7 years, p < 0.001), more likely to be female (31.0% vs. 66.4%, p < 0.001), and had a higher prevalence of previous ischemic stroke (13.4% vs. 20.2%, p = 0.026) and chronic heart failure (3.6% vs. 10.2%, p = 0.001). Consistent with the above findings, the low-dose apixaban group had higher post-stroke CHA2DS2-VASc scores than the standard-dose group (median [IQR]: 4 [3,4,5] versus 5 [4,5,6], p < 0.001).

Intravenous thrombolysis and EVT were performed more frequently in the standard-dose apixaban group than in the low-dose apixaban group (IV rt-PA, 47.0% vs. 34.5%, p = 0.001; EVT, 60.1% vs. 51.1%, p = 0.026). Effective endovascular revascularization, defined as mTICI 2b or 3, was observed more frequently in the standard-dose group than in the low-dose group (95.5% vs. 87.2%, p < 0.001). The median duration from onset to apixaban administration was 3.5 ± 3.0 days in the standard-dose group compared to 4.0 ± 3.4 days in the low-dose group (p = 0.062).

Outcomes

The cumulative incidence of ischemic events tended to be higher in patients receiving low-dose apixaban (3.0%/year vs. 6.7%/year, log-rank p = 0.086, Fig. 2a, Table 2). The crude hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic events in patients on low-dose apixaban was 2.06 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.90–4.72). The adjusted HR for ischemic events in patients on low-dose apixaban was 2.12 (95% CI 0.85–5.25) after adjustment for clinically relevant variables (Table 2). In the subgroup analyses, low-dose apixaban was associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke in patients with EVT; however, no interactions were observed in any subgroup analysis (Supplemental Table 1).

Patients on standard-dose apixaban had a similar rate of major bleeding events as patients on low-dose apixaban (6.6%/year vs. 7.6%/year, log-rank p = 0.82, Fig. 2b, Table 2). Compared with the standard-dose apixaban group, the crude HR for major bleeding events in the low-dose apixaban group was 1.08 (95% CI 0.56–2.07). Additionally, the adjusted HR for major bleeding events in the low-dose apixaban group was 1.17 (95% CI: 0.50–2.73) after adjustment for clinically relevant variables (Table 2). No associations were observed between apixaban dose and major bleeding events in any subgroup analysis (Supplemental Table 2).

The cumulative incidence of death from any cause was significantly higher in the low-dose apixaban group than in the standard-dose group (3.0%/year vs. 13.8%/year, log-rank p < 0.001, Fig. 2c, Table 2). The crude HR for death from any cause in the low-dose apixaban group was 4.55 (95% CI: 2.17–9.53). However, after adjustment for clinically relevant variables, low-dose apixaban was no longer associated with death from any cause compared with standard-dose apixaban (adjusted HR: 1.95, 95% CI: 0.78–4.89; Table 2). In addition, subgroup analyses showed that low-dose apixaban was not associated with death from any cause when stratified according to age (80 years). (Supplemental Table 3).

In the sensitivity analyses, the adjusted HR for ischemic events in patients on low-dose apixaban was 1.95 (95% CI: 0.85–4.46, p = 0.12; Supplemental Table 4). For the bleeding events, the HR for patients on low-dose apixaban was 0.97 (95% CI 0.50–1.88, p = 0.92; Supplemental Table 5). For death from any cause, the HR in patients on low-dose apixaban was 2.00 (95% CI 0.81–4.93, p = 0.13; Supplemental Table 6). These results were consistent with those of the main analyses.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the incidence of ischemic events tended to be higher, the incidence of hemorrhagic events did not differ, and mortality from any cause was higher in patients with acute stroke treated with low-dose apixaban than in those treated with standard-dose apixaban. However, this difference disappeared when confounding factors were corrected. These results do not indicate an increased risk of ischemic/bleeding events or mortality in patients receiving low-dose apixaban after LVO stroke.

Several studies have compared the morbidity of standard-dose versus low-dose apixaban in patients with AF [2,3,4,5]. These studies concluded that ischemic and bleeding events were comparable or more likely to occur in patients receiving low-dose apixaban than in those receiving standard-dose apixaban. However, these results are considered to reflect the comorbidities of the patients, as low-dose apixaban was not associated with ischemic and bleeding events when adjusted for age and other factors. Similar results were observed in specific patient groups at a higher risk of ischemic and bleeding events. For example, in older persons or patients with a history of ischemic stroke, who are prone to developing ischemic and hemorrhagic events, no significant differences in ischemic and bleeding events were observed between patients taking standard- and low-dose apixaban [5, 18]. LVO leads to large ischemic lesions, and patients with large ischemic lesions are at a higher risk of recurrent stroke and major bleeding [9]. The present study showed that recurrent stroke and major bleeding were not significantly different between standard and low apixaban doses in patients with acute LVO.

Previous studies have reported that patients administered low-dose apixaban were associated with increased mortality compared to patients administered standard-dose apixaban [3, 5], which is consistent with the univariate analysis results in the present study. In this study, the difference in mortality between patients taking standard- and low-dose apixaban disappeared after adjusting for clinically relevant factors or when stratified by age (80 years). This finding suggests that underlying factors such as age are responsible for the increased mortality observed in patients taking low-dose apixaban.

The strengths of this study include the large registry of acute ischemic stroke due to LVO and AF and the use of a single DOAC for stroke prevention. However, this study had several limitations. First, although the patients of this study received apixaban as instructed, the rate of inappropriately high or low doses of apixaban could not be analyzed because the ALVO study, which primarily planned to confirm the safety of early administration of apixaban, did not collect body weight data. Several real-world studies demonstrated that 25–36% of patients were administered receiving inappropriately doses of apixaban [2, 4, 19]. The results of this study reflect the real-world practice but not reflect the on-label use of apixaban. Second, the possibility of residual confounding by unmeasured factors such as frailty status or body weight still exists. Several studies reported that atrial fibrillation in frail or low body weight patients was associated with a higher risk of all-cause death, ischemic stroke, and bleeding [20,21,22,23]. Patients eligible for apixaban dose reduction also had a higher prevalence of frailty or low body weight, which may have influenced the outcomes. Third, the choice of apixaban and the timing of apixaban initiation after ischemic stroke were at the discretion of the treating physician. It is possible that some patients had a recurrent stroke before starting apixaban and were excluded from the study. In this study, the median days from onset to apixaban administration were 3.5 and 4 days in the standard- and low-dose apixaban groups, respectively, which is comparable to the most recent recommendation [24]. Finally, the findings of this study cannot be generalized to other population groups or DOACs. Each DOAC has different criteria for dose adjustment; thus, evaluating the efficacy and safety of multiple low-dose DOACs is difficult.

Conclusion

No statistically significant differences were observed in the incidence of ischemic events, major bleeding events, or death from any cause between patients with AF after LVO stroke who received standard-dose apixaban and those who received low-dose apixaban.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al-Khalidi HR, Ansell J, Atar D, Avezum A et al (2011) Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 365:981–992. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1107039

Inoue H, Umeyama M, Yamada T, Hashimoto H, Komoto A, Yasaka M (2020) Safety and effectiveness of reduced-dose apixaban in Japanese patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in clinical practice: a sub-analysis of the STANDARD study. J Cardiol 75:208–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjcc.2019.07.007

Chan YH, See LC, Tu HT, Yeh YH, Chang SH, Wu LS, Lee HF, Wang CL, Kuo CF, Kuo CT (2018) Efficacy and safety of apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and warfarin in Asians with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 7:e008150. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.008150

Salameh M, Gronich N, Stein N, Kotler A, Rennert G, Auriel E, Saliba W (2020) Stroke and bleeding risks in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with reduced apixaban dose: a real-life study. Clin Pharmacol Ther 108:1265–1273. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.1952

Okumura K, Yamashita T, Suzuki S, Akao M, Investigators J-ELDAF (2020) A multicenter prospective cohort study to investigate the effectiveness and safety of apixaban in Japanese elderly atrial fibrillation patients (J-ELD AF Registry). Clin Cardiol 43:251–259. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.23294

González-Pérez A, Roberts L, Vora P, Saez ME, Brobert G, Fatoba S, García Rodríguez LA (2022) Safety and effectiveness of appropriately and inappropriately dosed rivaroxaban or apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a cohort study with nested case-control analyses from UK primary care. BMJ Open 12:e059311. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059311

Cho MS, Yun JE, Park JJ, Kim YJ, Lee J, Kim H, Park DW, Nam GB (2019) Outcomes after use of standard- and low-dose non-vitamin k oral anticoagulants in asian patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke 50:110–118. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023093

Staerk L, Gerds TA, Lip GYH, Ozenne B, Bonde AN, Lamberts M, Fosbøl EL, Torp-Pedersen C, Gislason GH, Olesen JB (2018) Standard and reduced doses of dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. J Intern Med 283:45–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12683

Paciaroni M, Agnelli G, Falocci N, Caso V, Becattini C, Marcheselli S, Rueckert C, Pezzini A, Poli L, Padovani A et al (2015) Early recurrence and cerebral bleeding in patients with acute ischemic stroke and atrial fibrillation: effect of anticoagulation and its timing: the RAF Study. Stroke 46:2175–2182. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008891

Yoshimura S, Uchida K, Sakai N, Imamura H, Yamagami H, Tanaka K, Ezura M, Nonaka T, Matsumoto Y, Shibata M et al (2021) Safety of early administration of apixaban on clinical outcomes in patients with acute large vessel occlusion. Transl Stroke Res 12:266–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-020-00839-4

Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJGM (2010) Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest 137:263–272. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-1584

van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJ, van Gijn J (1988) Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 19:604–607. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.19.5.604

Lyden P, Brott T, Tilley B, Welch KM, Mascha EJ, Levine S, Haley EC, Grotta J, Marler J (1994) Improved reliability of the NIH Stroke Scale using video training. NINDS TPA Stroke Study Group Stroke 25:2220–2226. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.25.11.2220

Zaidat OO, Yoo AJ, Khatri P, Tomsick TA, von Kummer R, Saver JL, Marks MP, Prabhakaran S, Kallmes DF, Fitzsimmons B-FM et al (2013) Recommendations on angiographic revascularization grading standards for acute ischemic stroke: a consensus statement. Stroke 44:2650–2663. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001972

von Kummer R, Broderick JP, Campbell BCV, Demchuk A, Goyal M, Hill MD, Treurniet KM, Majoie CBLM, Marquering HA, Mazya MV et al (2015) The Heidelberg bleeding classification: classification of bleeding events after ischemic stroke and reperfusion therapy. Stroke 46:2981–2986. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010049

Schulman S, Kearon C, Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (2005) Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost 3:692–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x

Kanda Y (2013) Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 48:452–458. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2012.244

Yasaka M, Umeyama M, Kataoka H, Inoue H (2020) Secondary stroke prevention with apixaban in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: A subgroup analysis of the STANDARD study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 29:105034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105034

García Rodríguez LA, Martín-Pérez M, Vora P, Roberts L, Balabanova Y, Brobert G, Fatoba S, Suzart-Woischnik K, Schaefer B, Ruigomez A (2019) Appropriateness of initial dose of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in the UK. BMJ Open 9:e031341. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031341

Proietti M, Romiti GF, Raparelli V, Diemberger I, Boriani G, Dalla Vecchia LA, Bellelli G, Marzetti E, Lip GY, Cesari M (2022) Frailty prevalence and impact on outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 1,187,000 patients. Ageing Res Rev 79:101652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2022.101652

Wilkinson C, Todd O, Clegg A, Gale CP, Hall M (2019) Management of atrial fibrillation for older people with frailty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 48:196–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy180

Krittayaphong R, Chichareon P, Komoltri C, Kornbongkotmas S, Yindeengam A, Lip GYH (2020) Low body weight increases the risk of ischemic stroke and major bleeding in atrial fibrillation: the COOL-AF registry. J Clin Med Res 9:2713. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092713

Hamatani Y, Ogawa H, Uozumi R, Iguchi M, Yamashita Y, Esato M, Chun YH, Tsuji H, Wada H, Hasegawa K et al (2015) Low body weight is associated with the incidence of stroke in atrial fibrillation patients—insight from the fushimi AF registry. Circ J 79:1009–1017. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-14-1245

Kimura S, Toyoda K, Yoshimura S, Minematsu K, Yasaka M, Paciaroni M, Werring DJ, Yamagami H, Nagao T, Yoshimura S et al (2022) Practical “1-2-3-4-Day” rule for starting direct oral anticoagulants after ischemic stroke with atrial fibrillation: combined hospital-based cohort study. Stroke 53:1540–1549. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.036695

Acknowledgements

We thank all the investigators and collaborators for their efforts in conducting the ALVO Investigators Study Organization. The list of research collaborators other than the authors is provided in Supplemental Table 7.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Osaka University. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number JP20K07885).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

K. Todo reports lecture fees from Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Bayer. K. Uchida reports lecturer’s fees from Daiichi Sankyo. H. Yamagami discloses research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb; lecturer’s fees from Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Otuska Pharmaceutical, Stryker and Medtronic; and membership of the advisory boards for Daiichi Sankyo. N. Sakai reports lecturer’s fees from Daiichi Sankyo. S. Yoshimura discloses research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb and lecturer’s fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Bayer, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. T. Morimoto reports lecturer’s fees from Daiichi Sankyo and Pfizer, a manuscript fee from Pfizer, and membership of the advisory boards for Bristol-Myers Squibb. No other disclosures were reported.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all methods were carried out per the relevant guidelines and regulations for observational studies. The institutional review boards of all 38 participating centers approved the study protocol. This procedure was approved by the institutional review boards in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects in Japan.

Consent to participate

A written informed consent was obtained from the prospectively registered patients and from the opt-out method from the retrospectively registered patients.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murakami, Y., Todo, K., Uchida, K. et al. One-year morbidity and mortality in patients treated with standard-dose and low-dose apixaban after acute large vessel occlusion stroke. J Thromb Thrombolysis 57, 622–629 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-024-02954-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-024-02954-7