Abstract

We tested how 5 simple variables, routinely collected in primary care (i.e., the 3 AUDIT-C items, age, and sex), could constitute a clinician-friendly risk calculator tool of the 3-year risk of several alcohol-related adverse outcomes (i.e., alcohol use disorder, withdrawal symptoms, occurrence of tremors or seizures, and alcohol related interpersonal relationship problems, legal problems, and psychological problems) among non-alcohol-dependent individuals consuming alcohol. Data were drawn from a nationally representative sample of US adults, the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (wave 1, 2001–2002; wave 2, 2004–2005). We used scaled and rounded composite scoring systems to combine information derived from these predictors and quantify the risks for each subject. Analyses were limited to 16,710 respondents without a lifetime history of alcohol use disorder who completed both interviews and had consumed alcohol during the year prior to wave 1 (development sample N = 8355, validation sample N = 8355). The risk equations calibrated well (Hosmer and Lemeshow test p values ≥ 0.072) and showed good predictive values (C indices ranging from 0.727 to 0.872) in the validation sample. This risk calculator can be clinically useful in primary care for identification of at-risk individuals, encourage respondents to reduce their drinking, and improve prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Alcohol use is a leading cause of preventable premature death worldwide, accounting for some 3 million or 5.3% of premature global deaths (World Health Organization Team et al., 2018). Almost half of alcohol attributable to disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) are due to non-communicable diseases and mental health conditions, and about 40% are due to injuries (World Health Organization Team et al., 2018). These harms are related to both the overall volume of alcohol consumption and the pattern of drinking (Rehm et al., 2009, 2010). Developing an easy-to-use clinical tool to predict adverse outcomes of alcohol consumption (i.e., a risk calculator) among non-alcohol dependent individuals is crucial to help refine prevention strategies and promote early detection and treatment of high-risk individuals (Birmaher et al., 2018; Cannon et al., 2016; Fusar-Poli et al., 2017).

Robust evidence supports the effectiveness of screening and brief alcohol interventions in healthcare settings (Ballesteros et al., 2004; Kaner et al., 2013). While the content and delivery style of brief interventions varies (Whitlock et al., 2004), their success relies in part on their ability to promote awareness of the negative effects of drinking and to motivate positive behavior change (Ballesteros et al., 2004; Rolland et al., 2017). Most brief intervention guidelines recommend the use of the short-form 3-item AUDIT-C questionnaire for the screening of alcohol misuse (i.e., hazardous use or alcohol use disorders) (Bush, 1998; Rubinsky et al., 2013). AUDIT-C cut-off scores for alcohol misuse screening in men and women are used for discussing physicians’ concerns and for recommending reductions in alcohol consumption to the patient. However, adoption of those interventions is limited because, at present, those cut-offs do not allow (i) to determine precisely individuals’ risks of adverse outcomes, which may be differentially influenced by both the overall volume of alcohol consumption and the pattern of drinking (Rehm et al., 2010), and (ii) to deliver truly personalized information based on their specific drinking behavior. For example, although psychological, social, and medical consequences of hazardous alcohol drinking are often known (McCambridge, 2013), they often have low salience, especially for people with a focus on immediate rewards, such as individuals with substance use disorders. In addition, individuals with hazardous alcohol use tend to underestimate the short-term social consequences of their alcohol use (Grosso et al., 2013; Mallett et al., 2008; Oleski et al., 2010). Developing a clinician-friendly risk calculator for important medical, psychological, and social risks associated with different patterns of consumption within a timeframe relevant to most drinkers could help care providers deliver more personalized and effective feedback (Dotson et al., 2015).

Prior research suggests that the dimensions of alcohol consumption assessed by the AUDIT-C (i.e., past-year drinking frequency, average number of drinks consumed when drinking alcohol, and heavy drinking frequency) are significantly associated with alcohol-related adverse outcomes, including AUD severity (Rubinsky et al., 2013), depression (Levola & Aalto, 2015), suicide attempt (Hoertel et al., 2018), post-operative complications (Bradley et al., 2011), trauma (Williams et al., 2012), and social consequences such as divorce/separation, revocation of driving license or social isolation (Begg et al., 2017; Blanco et al., 2021, 2023; Franco et al., 2019; Hoertel et al., 2014a, b, c; Hoertel et al., 2014a, b, c). However, these prior studies have not examined the predictive power of the AUDIT-C scores for these outcomes. Thus, the predictions may yield many false positives and negatives, particularly because the relationship between AUDIT-C scores and adverse outcomes may vary by sex (Levola & Aalto, 2015; Rubinsky et al., 2013) and age (Lapham et al., 2014). In addition, the optimal AUDIT-C cut-off score may vary by adverse outcome.

In this study, we present the development and testing of a risk calculator, using composite scoring systems, to predict several important incident alcohol-related adverse outcomes (i.e., alcohol use disorder, interpersonal relationship problems, withdrawal symptoms, legal problems, psychological problems, and the occurrence of tremors or seizures) among non-alcohol-dependent individuals consuming alcohol, using a longitudinal nationally representative sample, the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Composite scoring systems allow combining information derived from several risk factors and aim at quantifying the risk for each subject (Coste et al., 1997). To simplify the scoring and facilitate its use, we scaled and rounded the regression coefficients in the final model to the nearest integer (Moons et al., 2002). By using a large national sample, we sought to obtain stable estimates that could be generalized beyond clinical samples.

Methods

Sample

Data were drawn from wave 1 and wave 2 of the NESARC, a nationally representative face-to-face survey of the US adult population, conducted in 2001–2002 (wave 1) and 2004–2005 (wave 2) by the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA) (Grant et al., 2009) with 43,093 participants (Grant et al., 2009). The target population included the civilian noninstitutionalized population, aged 18 years and older, residing in the USA. The overall response rate at wave 2 was 70.2%, resulting in 34,653 wave 2 interviews (Grant et al., 2009). The wave 2 NESARC data were weighted to adjust for non-response, demographic factors and psychiatric diagnoses, to ensure that the wave 2 sample approximated the target population. The research protocol, including written informed consent procedures, received full human subjects review and approval from the US Census Bureau and the Office of Management and Budget (Canino et al., 1999).

This analysis includes the 16,710 participants who participated to both waves, had consumed alcohol during the year preceding the wave 1 interview and did not have a lifetime history of alcohol use disorder (eFigure 1). We randomly split this sample of 16,710 participants into two samples: a development sample (N = 8355) and a validation sample (N = 8355).

Assessment of the Three-Year Risk of Incident Alcohol-Related Adverse Outcomes Between the Two Waves

Alcohol use disorder (AUD), i.e., alcohol abuse or dependence, was diagnosed using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV-TR version (AUDADIS-IV), a structured diagnostic instrument administered by trained lay interviewers (Grant et al., 2009). The test–retest reliability and validity of the AUDADIS-IV measures of AUD were good (Cohen’s kappa = 0.74) (Canino et al., 1999; Grant et al., 2003). Interpersonal relationship problems, withdrawal symptoms, legal problems, psychological problems, and the occurrence of tremors or seizures were assessed in wave 2, as detailed in eTable 1. Only incident adverse outcomes between the two waves were considered in all analyses.

Predictors: the 3 AUDIT-C Items, Sex, and Age

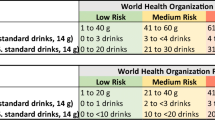

AUDIT-C is a validated brief screening scale to identify individuals with alcohol use disorder appropriate for routine screening in primary care (Bush, 1998; Rubinsky et al., 2013). The operationalization of the 3 items of the AUDIT-C (i.e., past-year drinking frequency, average drinks consumed when drinking alcohol, and heavy drinking frequency) is shown in eTable 2. To reduce the risk of multicollinearity across these 3 items, we collapsed a priori heavy drinking frequency into 3 categories: never, less than monthly, and at least monthly. Sex and age were self-reported. Age was categorized into 5 classes, i.e., 18–30 years, 31–40 years, 41–50 years, 51–64 years, and 65 years or more. We used the same set of predictors for each outcome (eTable 3).

Statistical Analyses

This analysis includes the 16,710 participants who participated to both waves, had consumed alcohol during the year preceding the wave 1 interview and did not have a lifetime history of alcohol use disorder (eFigure 1). We randomly split this sample of 16,710 participants into two samples: a development sample (N = 8355) and a validation sample (N = 8355) (eFigure 1). There were no between-sample significant differences in AUDIT-C items, sex, and age (eTable 3). We used the same set of predictors for each outcome.

Risk Calculator Development

First, we examined the bivariate relationships of the 3 items of AUDIT-C, sex, and age with the risk of developing each outcome in a 3-year follow-up period in the development sample. The risk calculator was developed using stepwise regression modeling. That procedure was used to select significant (i.e., p value < 0.05) explanatory variables for each outcome. To develop the risk calculator, we used combined procedures of forward and backward selection. Next, we performed composite scoring systems to combine information derived from these predictors and quantify the risks of alcohol-related incident adverse outcomes for each subject.

Discrimination and calibration of the risk calculator were examined for each outcome using Harrel’s C index, which reflects the proportion of all possible pairs of participants, one with the event and one without it, that are concordant (Steyerberg et al., 2001). The C index is equal to the area under a “receiver operating characteristic” curve. A C index of 0.5 indicates that the model is not better than chance at predicting an outcome. A C index ≥ 0.7 indicates a good model and a C index ≥ 0.8 a very good model (Steyerberg et al., 2010). Calibration measures the agreement between observed risk and predicted risk. We assessed the calibration of the calculator using the Hosmer and Lemeshow (H–L) test (Hosmer et al., 1997). The H–L test calculates if the observed event rates match the expected event rates in population subgroups. Models for which expected and observed event rates in subgroups are similar are called well calibrated. The H–L test is obtained by calculating the Pearson chi-square statistic from the 2 × g table of observed and expected frequencies, where g = 10 is the number of groups formed by deciles of risk. This statistic has an asymptotic χ2 (g — 2) distribution. P values ≤ 0.05 indicate poor calibration and larger p values (> 0.05 and > 0.5) indicate adequate and good calibration, respectively (Steyerberg et al., 2001).

To simplify the scoring and facilitate its use, especially in cases of limited access to computers or internet, the regression coefficients were scaled and rounded to integers on a range from 0 to 20 (Moons et al., 2002), so that risks can be calculated simply by hand. We subsequently checked that the resulting scaled/rounded to integers coefficients provided discrimination and calibration similar to those provided by the original coefficients. For each outcome, the risk calculator provided both the absolute risk and the risk ratio compared with individuals having the lowest alcohol consumption in wave 1.

All analyses accounted for the complex sampling design of the NESARC (Lumley, 2004) and were performed with R software version 4.3.1 (R Core Team, 2022). We evaluated statistical significance using a two-sided design with alpha set a priori at 0.05.

Risk Calculator Validation

We applied the risk equations derived from the development sample to the validation sample and calculated C indices for discrimination and the H–L test for calibration.

We also examined whether the predictive value (i.e., C index and its standard error) of the risk calculator for each outcome was significantly better than that obtained when simply using the AUDIT-C global score with different binary thresholds as predictor in the validation sample (DeLong et al., 1988; Hanley & McNeil, 1982; R Core Team, 2022).

Results

Among the 8355 participants from the development sample who consumed alcohol in the year preceding the wave 1 interview and had no lifetime history of AUD. At the time of the wave 2 interview, 6.0% (N = 498) had an incident diagnosis of AUD, 2.1% (N = 177) reported incident interpersonal relationship problems, 393 (4.7%) withdrawal symptoms, 1.3% (N = 107) incident legal problems, 2.5% (N = 208) incident psychological problems, and 1.7% (N = 149) incident tremors or seizures during the 3-year follow-up period. AUDIT-C items, sex, and age were significantly associated with all outcomes, except sex with withdrawal symptoms and interpersonal problems, age with tremors or seizures, and heavy drinking frequency with alcohol use disorder (eTables 4 and 5).

The C indices and the H–L tests for the risk calculator of each outcome in the development sample are shown in Table 1, while ROC curves are shown in eFigure 2. The calculator demonstrated good to very good discriminant power, with C indices ranging from 0.756 (alcohol use disorder) to 0.857 (legal problems), and adequate calibration with H–L test p values ranging from 0.153 (alcohol use disorder) to 0.678 (legal problems). There was no substantial loss of discrimination due to the use of scaled/rounded coefficients (Table 1). When applying the calculator to the validation sample (N = 8,355), our results indicated that they had a good to very good discriminant power, with C indices ranging from 0.727 (withdrawal symptoms) to 0.872 (legal problems) and a good calibration with H–L test p values ranging from 0.072 (alcohol use disorder) to 0.679 (interpersonal problems) (Table 1).

The predictive values of the risk calculator were significantly and substantially better than those of models including the AUDIT-C global score as predictor, whatever the binary threshold used (differences in C indices ranging from 0.042 to 0.217) (eTable 6). The only exception was tremor or seizures; which predictive values did not significantly differ from those including the AUDIT-C global score with a threshold of ≥ 3 as predictor (Z (df) = 1.96 (3449); p = 0.050) for all patients.

The equations underlying the risk calculator for the 6 alcohol-related incident adverse outcomes examined at wave 2 are shown in Table 2 and Figs. 1 and 2. For example, our results indicate that the 3-year risk for interpersonal relationship problems for a 20-year-old (4 points) man (1 point) with no lifetime history of AUD drinking 2–4 times a month (2 points) with 3 or 4 drink per day (3 points) and who has 5 or more drinks in a single day at least once every month (7 points), thus for whom the total score is equal to 17 points (Table 2; Fig. 2), would have an absolute risk of 8.9% of developing interpersonal relationship problems in a 3-year period (Fig. 1), representing a 89-fold higher risk than male drinkers having the lowest alcohol consumption (Fig. 2). Additionally, our results indicate that only 8.3% of the US general population of adult drinkers would have a greater risk of developing interpersonal relationship problems than this particular individual (Fig. 2).

Discussion

In a large, nationally representative sample of adults without a lifetime history of alcohol use disorder and consuming alcohol, we developed and validated a risk calculator for the 3-year risk of 6 alcohol-related medical, psychological, and social consequences, including incident alcohol use disorder, interpersonal relationship problems, withdrawal symptoms, legal problems, psychological problems, and tremors or seizures. The risk calculator was based on only 5 questions (i.e., past-year drinking frequency, average drinks consumed when drinking alcohol, frequency of heavy drinking, sex, and age) and allowed to quantify these risks within a timeframe likely to be relevant to most drinkers (i.e., 3 years). The calculator demonstrated good to very good predictive values (c indices ranging from 0.727 to 0.872) and calibrated well (all Hosmer and Lemeshow test p values ≥ 0.072) in the validation sample. The predictive values were significantly better than those of models including the AUDIT-C global score as predictor, whatever the binary threshold used, for all outcomes, except for “tremor or seizures”, and were well within the same range of other risk calculators for psychiatric disorders (Birmaher et al., 2018; Cannon et al., 2016; Fusar-Poli et al., 2017), whose C indices range from 0.71 to 0.79.

In line with prior studies (Begg et al., 2017; Dawson et al., 2012; Levola & Aalto, 2015; McCambridge, 2013), we found that the 3 dimensions of alcohol consumption assessed by the AUDIT-C (i.e., past-year drinking frequency, average drinks consumed when drinking alcohol, and frequency of heavy drinking) were independently associated with all adverse outcomes examined. The only exceptions were for heavy drinking frequency, which was not significantly associated with incident alcohol use disorder, and for the average number of drinks consumed, which was not associated with legal and psychological problems. This finding might be explained by a ceiling effect given the strong effects of both the drinking frequency and the number of drinks consumed when drinking alcohol on the risk of adverse alcohol-related consequences, and, potentially, by insufficient statistical power due to the relative limited number of incident adverse events in the 3-year follow-up period.

We found that younger age may increase risks of alcohol use disorder, interpersonal relationship problems, withdrawal symptoms, and legal problems beyond the effect of alcohol consumption. This result is in line with prior studies that suggest different magnitudes of effect of alcohol across different age groups (Begg et al., 2017; Denneson et al., 2011). Particularly, prior studies have shown that younger drinkers are more likely to have more adverse alcohol-related outcomes than older drinkers (Adams et al., 1990; Clemens et al., 2007; Molander et al., 2010). Interpersonal factors may negatively influence alcohol use at younger ages such as pacts with friends about drinking and celebration with influential peers, which are associated with heavier alcohol use and more negative alcohol-related consequences (Brister et al., 2010; Patrick et al., 2011).

Our study has several important implications. From a clinical perspective, this 5-question risk calculator is clinician-friendly and could be easily automatized or incorporated into the electronic medical record, or simply used by printing the charts attached in supplementary material translated in several languages (Annex 2). Given that age and sex are already systematically recorded, and that the AUDIT-C scoring is recommended by most clinical guidelines, the 5 items of the calculator could be available without any additional efforts from the clinician. The risk calculator may help promote early detection and treatment for high-risk individuals. By displaying the risks related to each pattern of consumption as well as the potential risk reduction that might be associated with alcohol consumption reduction, the calculator may provide an additional source of motivation for individuals with hazardous alcohol use, who often express a preference for reduction over abstinence (Aubin et al., 2015). From a public health perspective, an easy-to-use clinical tool may help policymakers design interventions in order to prevent alcohol use disorder and alcohol-related consequences in the general population (Birmaher et al., 2018; Cannon et al., 2016; Fusar-Poli et al., 2017).

This study has several limitations. First, alcohol consumption indicators and alcohol-related consequences were self-reported and may be subject to reporting and recall biases. Second, the risk equations have been validated in a randomly split subsample of the same database. Their validation in other general population samples, particularly in populations living outside the USA, is warranted to confirm their predictive values (Hoertel et al., 2014a, b, c). Finally, because we sought to build an easy-to-use clinical tool including only 5 items, our models do not capture other dimensions that can influence alcohol-related consequences, such as co-occurrence of other psychiatric disorders, access to mental health care, alcohol availability, stressful life events, and the protective role of social supports (Anderson & Baumberg, 2006; Glass et al., 1995).

In a large, nationally representative sample of drinkers, we developed an easy-to-use 5-question risk calculator with good to very good discrimination power to predict the 3-year risk of several important alcohol-related adverse outcomes, which can be calculated by hand using the attached chart (Fig. 2). To favor it use, we additionally translated it into 3 languages, i.e., French, Spanish, and Turkish (Appendix B). We hope that this risk calculator will be useful to identify, among adults without a lifetime history of alcohol use disorder and consuming alcohol, those at risk of developing alcohol-related adverse outcomes within a timeframe likely to be relevant to most drinkers (i.e., 3 years), encourage them to cut down their drinking and facilitate the implementation of focused preventive interventions in primary healthcare settings.

Data Availability

The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions was sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and funded, in part, by the Intramural Program, NIAAA, National Institutes of Health. The original dataset for the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) is available upon request from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (http://www.niaaa.nih.gov).

References

Adams, W. L., Garry, P. J., Rhyne, R., Hunt, W. C., & Goodwin, J. S. (1990). Alcohol intake in the healthy elderly: Changes with age in a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 38(3), 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03493.x

Anderson, P., & Baumberg, B. (2006). Alcohol in Europe – Public health perspective: Report summary. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 13(6), 483–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687630600902477

Aubin, H.-J., Reimer, J., Nutt, D. J., Bladström, A., Torup, L., François, C., & Chick, J. (2015). Clinical relevance of As-needed treatment with nalmefene in alcohol-dependent patients. European Addiction Research, 21(3), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1159/000371547

Ballesteros, J., Duffy, J. C., Querejeta, I., Ariño, J., & González-Pinto, A. (2004). Efficacy of brief interventions for hazardous drinkers in primary care: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 28(4), 608–618. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ALC.0000122106.84718.67

Begg, D., Brookland, R., & Connor, J. (2017). Associations of repeated high alcohol use with unsafe driving behaviors, traffic offenses, and traffic crashes among young drivers: Findings from the New Zealand drivers study. Traffic Injury Prevention, 18(2), 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2016.1224345

Birmaher, B., Merranko, J. A., Goldstein, T. R., Gill, M. K., Goldstein, B. I., Hower, H., Yen, S., Hafeman, D., Strober, M., Diler, R. S., Axelson, D., Ryan, N. D., & Keller, M. B. (2018). A risk calculator to predict the individual risk of conversion from subthreshold bipolar symptoms to bipolar disorder I or II in youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(10), 755-763.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.05.023

Blanco, C., Wall, M. M., Hoertel, N., Krueger, R. F., Liu, S.-M., Grant, B. F., & Olfson, M. (2021). Psychiatric disorders and risk for multiple adverse outcomes: A national prospective study. Molecular Psychiatry, 26(3), 907–916. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0459-4

Blanco, C., Wall, M. M., Hoertel, N., Krueger, R. F., & Olfson, M. (2023). Toward a generalized developmental model of psychopathological liabilities and psychiatric disorders. Psychological Medicine, 53(8), 3406–3415. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721005468

Bradley, K. A., Rubinsky, A. D., Sun, H., Bryson, C. L., Bishop, M. J., Blough, D. K., Henderson, W. G., Maynard, C., Hawn, M. T., Tønnesen, H., Hughes, G., Beste, L. A., Harris, A. H. S., Hawkins, E. J., Houston, T. K., & Kivlahan, D. R. (2011). Alcohol screening and risk of postoperative complications in male VA patients undergoing major non-cardiac surgery. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(2), 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1475-x

Brister, H. A., Wetherill, R. R., & Fromme, K. (2010). Anticipated versus actual alcohol consumption during 21st birthday celebrations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 71(2), 180–183. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2010.71.180

Bush, K. (1998). The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C) An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789

Canino, G., Bravo, M., Ramírez, R., Febo, V. E., Rubio-Stipec, M., Fernández, R. L., & Hasin, D. (1999). The Spanish Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): Reliability and concordance with clinical diagnoses in a Hispanic population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 60(6), 790–799. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1999.60.790

Cannon, T. D., Yu, C., Addington, J., Bearden, C. E., Cadenhead, K. S., Cornblatt, B. A., Heinssen, R., Jeffries, C. D., Mathalon, D. H., McGlashan, T. H., Perkins, D. O., Seidman, L. J., Tsuang, M. T., Walker, E. F., Woods, S. W., & Kattan, M. W. (2016). An individualized risk calculator for research in prodromal psychosis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(10), 980–988. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070890

Clemens, S. L., Matthews, S. L., Young, A. F., & Powers, J. R. (2007). Alcohol consumption of Australian women: Results from the Australian longitudinal study on women’s health. Drug and Alcohol Review, 26(5), 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230701499142

Coste, J., Bouyer, J., & Job-Spira, N. (1997). Construction of composite scales for risk assessment in epidemiology: An application to ectopic pregnancy. American Journal of Epidemiology, 145(3), 278–289. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009101

Dawson, D. A., Smith, S. M., Saha, T. D., Rubinsky, A. D., & Grant, B. F. (2012). Comparative performance of the AUDIT-C in screening for DSM-IV and DSM-5 alcohol use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 126(3), 384–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.029

DeLong, E. R., DeLong, D. M., & Clarke-Pearson, D. L. (1988). Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics, 44(3), 837–845.

Denneson, L. M., Lasarev, M. R., Dickinson, K. C., & Dobscha, S. K. (2011). Alcohol consumption and health status in very old veterans. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 24(1), 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988710390814

Dotson, K. B., Dunn, M. E., & Bowers, C. A. (2015). Stand-alone personalized normative feedback for college student drinkers: A meta-analytic review, 2004 to 2014. PLoS ONE, 10(10), e0139518. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139518

Franco, S., Olfson, M., Wall, M. M., Wang, S., Hoertel, N., & Blanco, C. (2019). Shared and specific associations of substance use disorders on adverse outcomes: A national prospective study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 201, 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.003

Fusar-Poli, P., Rutigliano, G., Stahl, D., Davies, C., Bonoldi, I., Reilly, T., & McGuire, P. (2017). Development and validation of a clinically based risk calculator for the transdiagnostic prediction of psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(5), 493. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0284

Glass, T. A., Prigerson, H., Kasl, S. V., & De Leon, C. F. M. (1995). The effects of negative life events on alcohol consumption among older men and women. The Journals of Gerontology Series b: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 50B(4), S205–S216. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/50B.4.S205

Grant, B. F., Dawson, D. A., Stinson, F. S., Chou, P. S., Kay, W., & Pickering, R. (2003). The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 71(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00070-X

Grant, B. F., Goldstein, R. B., Chou, S. P., Huang, B., Stinson, F. S., Dawson, D. A., Saha, T. D., Smith, S. M., Pulay, A. J., Pickering, R. P., Ruan, W. J., & Compton, W. M. (2009). Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Molecular Psychiatry, 14(11), 1051–1066. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2008.41

Grosso, J. A., Epstein, E. E., McCrady, B. S., Gaba, A., Cook, S., Backer-Fulghum, L. M., & Graff, F. S. (2013). Women’s motivators for seeking treatment for alcohol use disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 38(6), 2236–2245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.02.004

Hanley, J. A., & McNeil, B. J. (1982). The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology, 143(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747

Hoertel, N., Crochard, A., Limosin, F., & Rouillon, F. (2014a). La consommation excessive d’alcool: Un lourd fardeau pour l’entourage. L’encéphale, 40, S1–S10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2014.02.007

Hoertel, N., Crochard, A., Rouillon, F., & Limosin, F. (2014b). L’alcool en France et ses conséquences médicales et sociales: Regard de l’entourage et des médecins généralistes. L’encéphale, 40, S11–S31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2014.02.008

Hoertel, N., Falissard, B., Humphreys, K., Gorwood, P., Seigneurie, A.-S., & Limosin, F. (2014c). Do clinical trials of treatment of alcohol dependence adequately enroll participants with co-occurring independent mood and anxiety disorders?: An analysis of data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(03), 231–237. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08424

Hoertel, N., Faiz, H., Airagnes, G., Blanco, C., Pascal De Raykeer, R., Franco, S., Ducoutumany, G., Lemogne, C., & Limosin, F. (2018). A comprehensive model of predictors of suicide attempt in heavy drinkers: Results from a national 3-year longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 186, 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.01.010

Hosmer, D. W., Hosmer, T., Le Cessie, S., & Lemeshow, S. (1997). A comparison of goodness-of-fit tests for the logistic regression model. Statistics in Medicine, 16(9), 965–980. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19970515)16:9%3c965::AID-SIM509%3e3.0.CO;2-O

Kaner, E., Bland, M., Cassidy, P., Coulton, S., Dale, V., Deluca, P., Gilvarry, E., Godfrey, C., Heather, N., Myles, J., Newbury-Birch, D., Oyefeso, A., Parrott, S., Perryman, K., Phillips, T., Shepherd, J., & Drummond, C. (2013). Effectiveness of screening and brief alcohol intervention in primary care (SIPS trial): Pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 346(jan09 2), e8501–e8501. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8501

Lapham, G. T., Rubinsky, A. D., Heagerty, P. J., Achtmeyer, C., Williams, E. C., Hawkins, E. J., Maynard, C., Kivlahan, D. R., Au, D., & Bradley, K. A. (2014). Probability and predictors of patients converting from negative to positive screens for alcohol misuse. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 38(2), 564–571. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12260

Levola, J., & Aalto, M. (2015). Screening for at-risk drinking in a population reporting symptoms of depression: a validation of the AUDIT, AUDIT -C, and AUDIT -3. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(7), 1186–1192. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12763

Lumley, T. (2004). Analysis of complex survey samples. Journal of Statistical Software, 9(8). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v009.i08

Mallett, K. A., Bachrach, R. L., & Turrisi, R. (2008). Are all negative consequences truly negative? Assessing variations among college students’ perceptions of alcohol related consequences. Addictive Behaviors, 33(10), 1375–1381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.014

McCambridge, J. (2013). Brief intervention content matters. Drug and Alcohol Review, 32(4), 339–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12044

Molander, R. C., Yonker, J. A., & Krahn, D. D. (2010). Age-related changes in drinking patterns from mid- to older age: Results from the Wisconsin longitudinal study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(7), 1182–1192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01195.x

Moons, K. G. M., Harrell, F. E., & Steyerberg, E. W. (2002). Should scoring rules be based on odds ratios or regression coefficients? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 55(10), 1054–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00453-5

Oleski, J., Mota, N., Cox, B. J., & Sareen, J. (2010). Perceived need for care, help seeking, and perceived barriers to care for alcohol use disorders in a national sample. Psychiatric Services, 61(12), 1223–1231. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2010.61.12.1223

Patrick, M. E., Morgan, N., Maggs, J. L., & Lefkowitz, E. S. (2011). “I Got Your Back”: Friends’ understandings regarding college student spring break behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(1), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9515-8

R Core Team, (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 18 Mar 2024

Rehm, J., Mathers, C., Popova, S., Thavorncharoensap, M., Teerawattananon, Y., & Patra, J. (2009). Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The Lancet, 373(9682), 2223–2233. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7

Rehm, J., Baliunas, D., Borges, G. L. G., Graham, K., Irving, H., Kehoe, T., Parry, C. D., Patra, J., Popova, S., Poznyak, V., Roerecke, M., Room, R., Samokhvalov, A. V., & Taylor, B. (2010). The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: An overview. Addiction, 105(5), 817–843. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02899.x

Rolland, B., Naassila, M., Paille, F., Aubin, H.-J., & d’Alcoologie, S. F. (2017). The role of general practitioners in the 2015 French guidelines on alcohol misuse. Alcohol and Alcoholism (oxford, Oxfordshire), 52(6), 747–748. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agx054

Rubinsky, A. D., Dawson, D. A., Williams, E. C., Kivlahan, D. R., & Bradley, K. A. (2013). AUDIT-C scores as a scaled marker of mean daily drinking, alcohol use disorder severity, and probability of alcohol dependence in a U.S. general population sample of drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(8), 1380–1390. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12092

Steyerberg, E. W., Harrell, F. E., Borsboom, G. J. J. M., Eijkemans, M. J. C., Vergouwe, Y., & Habbema, J. D. F. (2001). Internal validation of predictive models. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(8), 774–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00341-9

Steyerberg, E. W., Vickers, A. J., Cook, N. R., Gerds, T., Gonen, M., Obuchowski, N., Pencina, M. J., & Kattan, M. W. (2010). Assessing the performance of prediction models: A framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology, 21(1), 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2

Whitlock, E. P., Polen, M. R., Green, C. A., Orleans, T., & Klein, J. (2004). Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: A summary of the evidence for the U.S. preventive services task force. Annals of Internal Medicine, 140(7), 557. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00017

Williams, E. C., Bryson, C. L., Sun, H., Chew, R. B., Chew, L. D., Blough, D. K., Au, D. H., & Bradley, K. A. (2012). Association between alcohol screening results and hospitalizations for trauma in veterans affairs outpatients. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2011.600392

World Health Organization Team, Vladimir, P., & Dag, R. (2018). Global status report on alcohol and health 2018 (p. 450). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639. Accessed 18 Mar 2024

Acknowledgements

The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions was sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and funded, in part, by the Intramural Program, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr Martin Blachier for his help in the development of our risk calculator. We are also grateful to Marie Dosquet, Marina Sánchez-Rico, and Katayoun Rezaei for their translation of the risk calculator into French, Spanish, and Turkish, respectively.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: N.H. and H.L. Formal analysis: N.H., M.S-R., J.G-C., K.R., and H.L. Writing—original draft: N.H., M.D., and F.L. Review and editing critically: C.B., H-J.A., G.D., P.G., M.S-R., H.L., G.A., C.L., K.R., and H.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or the US government. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

FL has received speaker and consulting fees from the AstraZeneca, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Roche, and Servier, outside the submitted work. CL reports personal fees and non-financial support from the Lundbeck, personal fees from Janssen, non-financial support from the Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. PG received research grants from the Eli Lilly and Servier; honoraria for presentations in congresses from the AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Lundbeck, and Servier; participated in advisory board with the AstraZeneca, Janssen, Roche, and Servier; has a paid position at the University of Paris-Descartes and hospital Sainte-Anne, and no shares. HL has a paid position at the Public Health Expertise. GA has received speaker and consulting fees from the Lundbeck and Pfizer. HJA was member of advisory boards for the Pfizer, D&A Pharma, Ethypharm, Johnson& Johnson, and Lundbeck, and has received sponsorship to attend scientific meetings, speaker honoraria and consultancy fees from the Bioprojet, D&A Pharma, Ethypharm, Lundbeck, and Pfizer. He is also member of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology’s Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative (ACTIVE), which was supported in the last three years by the AbbVie, Alkermes, Amygdala Neurosciences, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Ethypharm, Indivior, Lilly, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Pfizer. Other authors (NH, MD, CB, GD, HP, MSR, JGC, KR) report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoertel, N., Dosquet, M., Sánchez-Rico, M. et al. Development and Validation of a Simple Risk Calculator for Alcohol-Related Adverse Outcomes: Results from a Composite Scale Approach in a Nationally Representative Sample. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01278-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01278-0