Published online Mar 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i8.1536

Peer-review started: December 23, 2023

First decision: January 9, 2024

Revised: January 12, 2024

Accepted: February 20, 2024

Article in press: February 20, 2024

Published online: March 16, 2024

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) is the causative agent of TB, a chronic granulomatous illness. This disease is prevalent in low-income countries, posing a significant global health challenge. Gastrointestinal TB is one of the three forms. The disease can mimic other intra-abdominal conditions, leading to delayed diagnosis owing to the absence of specific symptoms. While gastric outlet obs

A 23-year-old male presented with recurrent epigastric pain, distension, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss, prompting a referral to a gastroenterologist clinic. Endoscopic examination revealed distorted gastric mucosa and signs of chronic inflammation. However, treatment was interrupted, possibly owing to vomiting or comorbidities such as human immunodeficiency virus infection or diabetes. Subsequent surgical intervention revealed a dilated stomach and diffuse thickening of the duodenal wall. Resection revealed gastric wall effacement with TB.

Primary gastric TB is rare, frequently leading to GOO. Given its rarity, suspicions should be promptly raised when encountering relevant symptoms, often requiring surgical intervention for diagnosis and treatment.

Core Tip: Tuberculosis (TB) is a disease that has been around since ancient times and is still one of the top 10 causes of death globally. With a high incidence in lower-income countries. It is a global health concern, with gastrointestinal TB The third most common extrapulmonary form of TB. Here we present Primary gastroduodenal TB presenting as gastric outlet obstruction (GOO): A case report and review of the literature. The diagnosis of abdominal TB is often delayed since there are no distinct clinical signs and symptoms, and the disease can mimic other intra-abdominal pathologies. The most common causes of GOO include peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer. TB should be included ddx when these dx is excluded. Surgery is inevitable when GOO is present at time of diagnosis and proceed by antitubercular treatment.

- Citation: Ali AM, Mohamed YG, Mohamud AA, Mohamed AN, Ahmed MR, Abdullahi IM, Saydam T. Primary gastroduodenal tuberculosis presenting as gastric outlet obstruction: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(8): 1536-1543

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i8/1536.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i8.1536

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic granulomatous disease caused by aerobic bacteria Mycobacterium TB[1,2].

Its global incidence is high in low-income nations, posing a significant health concern. TB has high morbidity and mortality rates despite its status as a treatable disease[3]. Abdominal TB ranks as the third most common extrapulmonary form[4].

Gastrointestinal TB (GI–TB) is one of the three forms of abdominal TB. The other types include visceral, peritoneal, and tuberculous lymphadenopathy[5].

Mycobacterium TB enters the gastrointestinal system via hematogenous spread, ingestion of contaminated sputum, or direct dissemination from infected adjacent lymph nodes and fallopian tubes[6,7].

Diagnosing abdominal TB is often hindered by the absence of distinct clinical signs and symptoms, leading to delayed identification because the disease can mimic other intra-abdominal pathologies[8,9].

Correcting the general status of patients with a confirmed diagnosis of GOO, administering intravenous fluids to correct an electrolyte imbalance, and performing gastric decompression by inserting a nasogastric tube are all essential to the initial management of these patients[10]. The most common causes of gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) are peptic ulcer disease (PUD) and gastric cancer. However, the frequency of GOO owing to PUD has declined since the deve

Gastric bezoars, pancreatitis-related fluid collection, caustic ingestion, massive gastric polyps, Crohn's disease, and complications following gastric surgery contribute to GOO[11].

Gastroduodenal TB (GD-TB) presents with various manifestations, including upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, obstruction, and gastric or periampullary tumors suggestive of malignancy[12].

Similar to our patient, most individuals with GD-TB exhibit signs of GOO, often attributed not only to intrinsic duodenal lesions but also to extrinsic compression by tuberculous lymph nodes[13].

Here, we present a case of GD-TB-associated GOO in a previously healthy 23-year-old patient who exhibited no signs of pulmonary TB.

A 23-year-old male patient came to the Department of Surgery with recurrent epigastric pain, vomiting, and weight loss that had persisted for a year despite the patient having no prior history of chronic illness.

The patient had a year-long history of recurrent epigastric pain, distension, low appetite, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss. He did not mention any fever, jaundice, or changes in bowel habits. Hemostasis and cough were absent, and there were no notable findings from the assessment of the other systems.

The patient had experienced similar symptoms during a prior stay in South Africa eight months earlier, during which an endoscopy revealed distortions and chronic inflammatory changes in the distal gastric mucosa without evidence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. Subsequently, anti-tubercular medication was planned, but the patient ceased treatment after one week owing to intractable vomiting.

There was no family history of similar conditions or TB.

The patient presented with normal vital signs, absence of pallor, and no cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy.

Clear chest examination findings were noted. Upon abdominal examination, the abdomen was soft and non-tender with mild distension, and no masses, organomegaly, or ascites were noted.

C-reactive protein 200 mg/L, stool H. Pylori-negative. No abnormalities were found in routine blood and urine analyses.

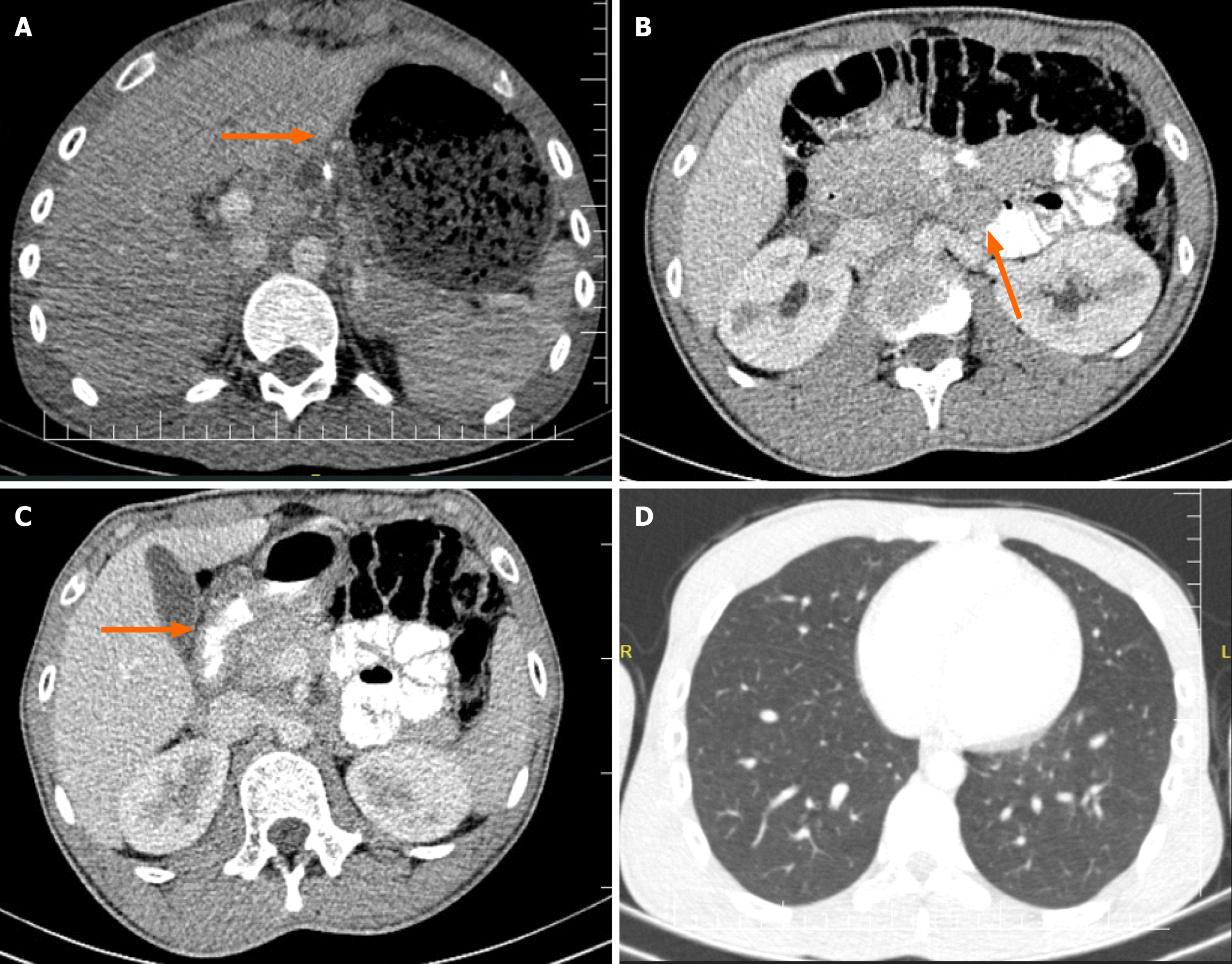

An abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan revealed gastric distension and diffuse wall thick

A gastric biopsy revealed chronic gastritis with severe inflammation, absence of metaplasia and dysplasia, and a positive result for H. pylori.

The patient was admitted for optimization of preoperative fitness in preparation for surgery.

Primary GD-TB.

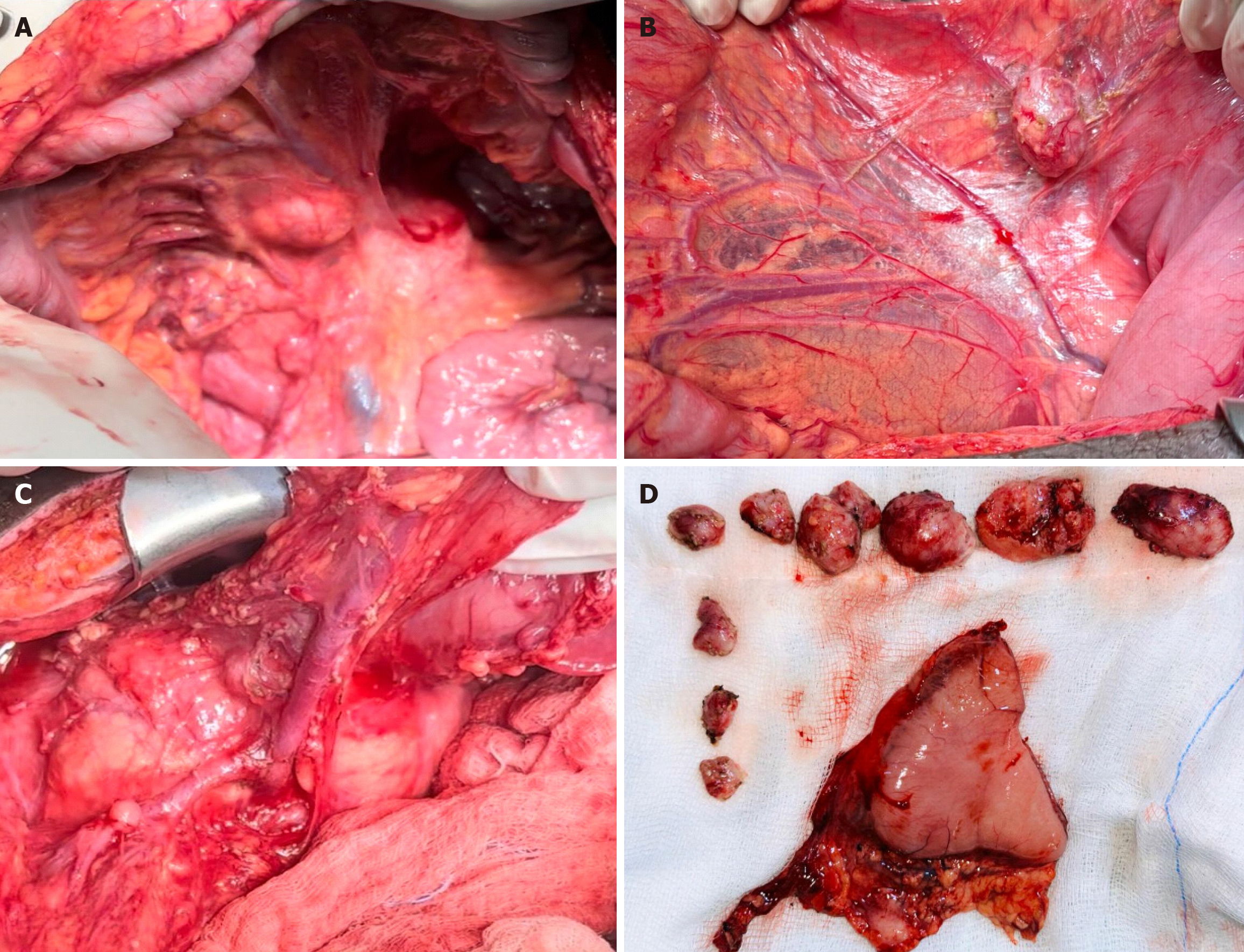

A decision was made to relieve the obstruction surgically. Intraoperatively, the following findings were noted: Dilation of the stomach and diffuse wall thickening of the duodenum, along with multiple enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes (located at the lesser curvature, transverse colon mesentery, small bowel mesentery, paraduodenal area, and interaortocaval region). Subsequently, antrectomy and Roux-en-Y reconstruction with gastrojejunostomy were performed, along with lymph node dissection (Figure 2).

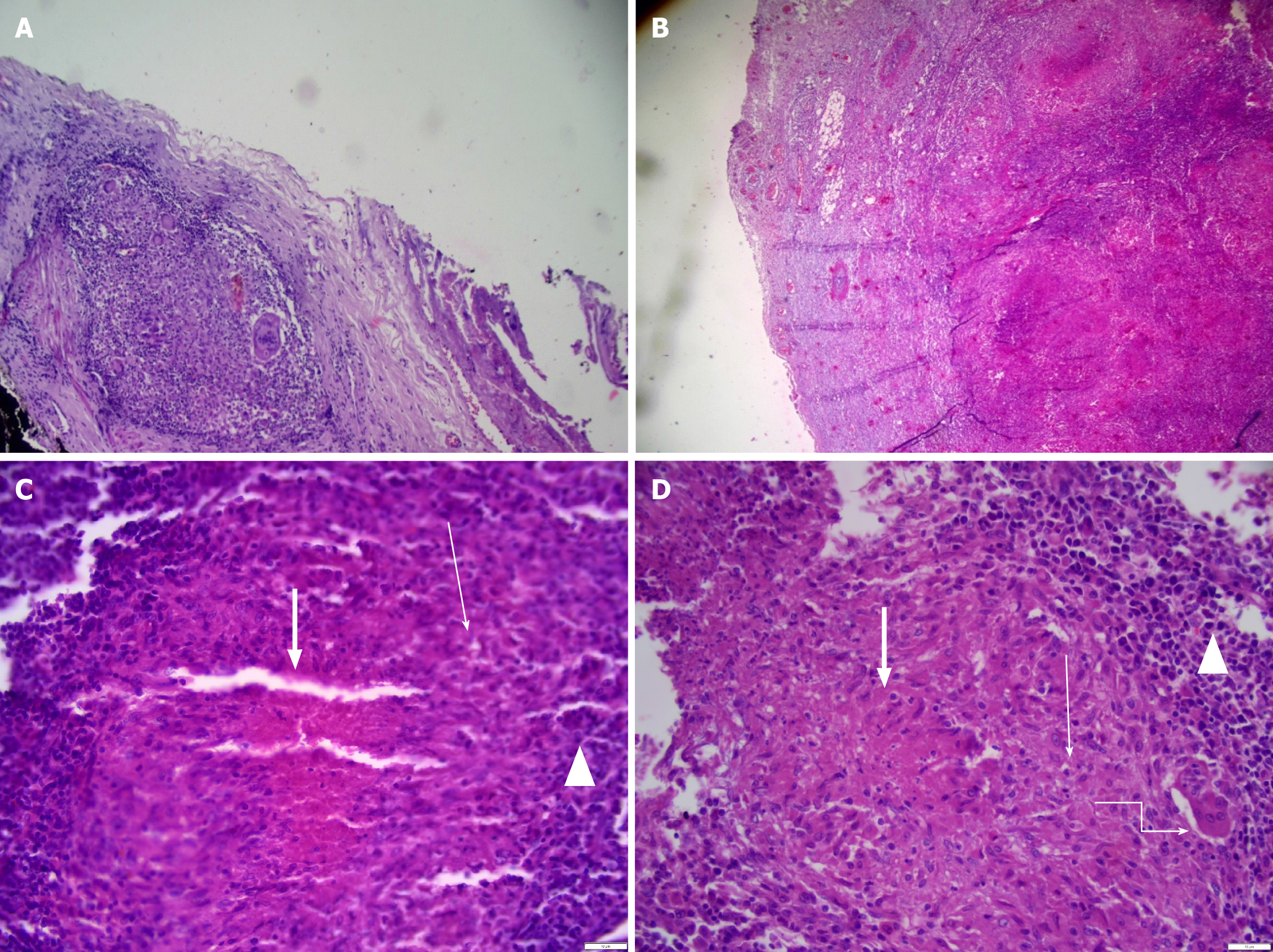

The pathology report from the resected distal part of the antrum and lymph nodes revealed findings indicative of gastric TB, characterized by effacement of the gastric wall architecture and numerous caseating granulomatous inflammation. Specifically, the distal margins displayed positivity for granulomatous inflammation. Additionally, 12 Lymph nodes exhibited suppurative and non-suppurative granulomatous inflammation, further supporting the TB diagnosis. Periodic Acid-Schiff stain stains yielded negative results for fungal hyphae. These findings were consistent with GD-TB (Figure 3). Notably, cytology analysis for Acid Fast Bacteria staining and Gene Xpert testing were not pursued owing to the absence of peritoneal ascites detected during the operation.

The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged from the hospital following successful tolerance of full enteral feeding. Plans were made for follow-up visits at the polyclinic and referral to a TB center to initiate anti-tubercular treatment. Currently, the patient is adhering to the anti-tubercular medication regimen well and has experienced no adverse effects.

GI–TB most frequently affects the ileocecal area, with the colon and jejunum following closely after. A total of 64% of GI–TB cases are caused by jejunal and ileocecal TB[14]. However, the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum are rarely affected. The duodenum and gastric are the primary sites of involvement for gastric TB.

Primary and isolated stomach TB is exceptionally rare, documented only in very few cases in the literature. A total of 0.4%–2% of all GI–TB cases are associated with primary gastric TB, while 2%–2.5% are associated with primary duodenal TB[15].

Several factors contribute to the low frequency of gastric TB, including the bactericidal properties of gastric acid, the presence of thick and intact gastric mucosa, and the absence of lymphoid structures in the gastric mucosa[14,16]. Treatment with H2 blockers increases the likelihood of involvement of the lesser curvature and pylorus in gastric TB, often presenting as ulcerating lesions[5]. Manifestations such as pyloric stenosis, miliary tubercles, and hypertrophic variations may also occur[14]. Gastric TB is frequently associated with TB lymphadenitis, as observed in cases where peripancreatic lymph nodes are involved, alongside visible ulcerative lesions in the prepyloric region.

The third part of the duodenum is commonly affected in cases of primary duodenal TB.

Both intrinsic and extrinsic factors can contribute to duodenal involvement[17]. Extrinsic involvement is most prevalent and is often related to lymphadenopathy in the duodenum's C-loop. Intrinsic variations may manifest as ulcerative, hypertrophic, or ulcer hypertrophic forms, potentially leading to fistula or stricture formation.

Various modalities contribute to GI–TB involvement, including ingestion of contaminated milk or food (primary TB), ingestion of contaminated sputum (secondary TB), hematogenous spread from a distant TB focus, or contiguous dissemination from infected neighboring foci via the lymphatic channels[18,19]. Given the absence of evidence of extra-abdominal TB in our case, we believe the infection to be primary gastric TB involving the peripancreatic lymph node.

GD-TB presents with nonspecific clinical characteristics commonly associated with weight loss, epigastric pain, and fever. In certain cases, GOO may be the presenting feature. Gastric TB may also mimic lymphoma or carcinoma, complicating the differential diagnosis. A study by Rao et al[12] conducted at a single center in India reported that among 23 patients with histologically confirmed GD-TB, vomiting (60.8%) and epigastric pain (56.5%) were the most prevalent presenting symptoms, with characteristics of GOO observed in 61% of cases (14 patients)[12]. While two patients had pyloric stenosis, the remaining twelve experienced obstruction owing to duodenal stricture. Additionally, out of the 23 patients studied, four had diabetes mellitus, and none were human immunodeficiency virus-positive. Similar to this study, our patient presented with vomiting, epigastric pain, and early satiety, suggestive of GOO.

The lack of specific clinical symptoms and diagnostic indicators often leads to underdiagnosis of GD-TB.

Histopathological examination of gastroduodenal biopsy specimens obtained via endoscopy remains the gold standard for diagnosing GD-TB. However, owing to the submucosal nature of granulomatous lesions, they are often challenging to identify, even in biopsy samples. A review revealed that granulomas were detected in only seven out of 27 patients who underwent endoscopic biopsy for duodenal TB[20].

Similarly, Rao et al[12] reported positive biopsies in their study in only 2 out of 20 patients.

Complications of GD-TB may include GOO, hemorrhage, and perforation, which can significantly increase morbidity[11].

As outlined in a review by Rao et al[12], in cases of TB-related GOO, truncal vagotomy and gastrojejunostomy (with or without feeding jejunostomy) were performed in twelve out of fourteen patients[12].

While abdominal TB can affect individuals of any age, there is a significant predominance among women, particularly those between the ages of 25 and 45[21]. In patients with GD-TB presenting with obstruction or mass, the yield of endoscopic biopsy is typically low[22,23].

Dyspeptic symptoms suggestive of gastric lesions often lead to suspicion of peptic ulcer, while weight loss may prompt consideration of gastric cancer as the primary diagnosis.

Up to 20% of patients undergoing examinations may exhibit evidence of pulmonary TB on chest X-ray[24], and duod

Although preoperative diagnosis of duodenal TB is exceedingly rare[17,26], Debi et al[14] have demonstrated that an endoscopic ultrasound is a valuable modality for characterizing lesions and obtaining samples for cytological confirmation[1]. In cases where histological diagnosis cannot be established by other means, intraoperative fine-needle aspiration cytology may be employed to obtain samples from the affected duodenal section[27].

Most lesions diagnosed with TB before surgery respond well to appropriate antitubercular treatment and may not require surgical intervention[28]. Antituberculosis medication therapy is the cornerstone of medical treatment for gastric TB. However, surgery becomes necessary for patients experiencing severe GOO owing to hypertrophic TB, with antitu

In cases of GOO, gastrojejunostomy is preferred over pyloroplasty owing to the severe fibrosis around the pyloro

This study adheres to the surgical case report guidelines 2016 criteria[30].

Primary gastric TB is rare and often poses a diagnostic challenge, particularly when it presents as GOO. In regions where TB is prevalent, heightened suspicion is warranted. Surgery is often essential for diagnosis and treatment.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Somalia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abid S, Pakistan S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao YQ

| 1. | Chai Q, Zhang Y, Liu CH. Mycobacterium tuberculosis: An Adaptable Pathogen Associated With Multiple Human Diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:158. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Arega B, Mersha A, Minda A, Getachew Y, Sitotaw A, Gebeyehu T, Agunie A. Epidemiology and the diagnostic challenge of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis in a teaching hospital in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0243945. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Guled AY, Elmi AH, Abdi BM, Rage AMA, Ali FM, Abdinur AH, Ali AA, Ahmed AA, Ibrahim KA, Mohamed SO, Mire FA, Adem OA, Osman AD. Prevalence of Rifampicin Resistance and Associated Risk Factors among Suspected Multidrug Resistant Tuberculosis Cases in TB Centers Mogadishu-Somalia: Descriptive Study. Open Journal of Respiratory Diseases. 2016;6:15-24. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Eraksoy H. Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Tuberculosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2021;50:341-360. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Rasheed S, Zinicola R, Watson D, Bajwa A, McDonald PJ. Intra-abdominal and gastrointestinal tuberculosis. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:773-783. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Awasthi S, Saxena M, Ahmad F, Kumar A, Dutta S. Abdominal Tuberculosis: A Diagnostic Dilemma. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:EC01-EC03. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Azad KAK, Chowdhury T. Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis (Eptb): An Overview. Bangladesh Journal of Medicine. 2022;33:130-137. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Ahmad QA, Sarwar MZ, Fatimah N, Ahmed AS, Changaizi SH, Ayyaz M. Acute Presentation and Management of Abdominal Tuberculosis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2020;30:129-133. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Govil S, Govil S, Eapen A. Imaging of Abdominal Solid Organ and Peritoneal Tuberculosis. In: Ladeb MF, Peh WCG, editor. Imaging of Tuberculosis. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022: 225-249. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Papanikolaou IS, Siersema PD. Gastric Outlet Obstruction: Current Status and Future Directions. Gut Liver. 2022;16:667-675. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Maliyakkal AM, Naushad VA, Shaath NM, Valiyakath HS, Farfar KL, Mohammed AM, Ahmed M. Gastroduodenal Tuberculosis Presenting as a Gastric Outlet Obstruction: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023;15:e49436. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Rao YG, Pande GK, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Gastroduodenal tuberculosis management guidelines, based on a large experience and a review of the literature. Can J Surg. 2004;47:364-368. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Molla YD, Kassa SA, Tadesse AK. Rare case of duodenal tuberculosis causing gastric outlet obstruction, a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023;105:108080. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Debi U, Ravisankar V, Prasad KK, Sinha SK, Sharma AK. Abdominal tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract: revisited. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14831-14840. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Padma V, Anand NN, Rajendran SM, Gurukal S. Primary tuberculosis of stomach. J Indian Med Assoc. 2012;110:187-188. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Choudhury A, Dhillon J, Sekar A, Gupta P, Singh H, Sharma V. Differentiating gastrointestinal tuberculosis and Crohn's disease- a comprehensive review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:246. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Bhatti A, Hussain M, Kumar D, Samo KA. Duodenal tuberculosis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2012;22:111-112. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Vlad RM, Smădeanu ER, Becheanu G, Darie R, Păcurar D. The diagnostic challenges in a child with intestinal tuberculosis. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2021;62:1057-1061. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Tinsa F, Essaddam L, Fitouri Z, Brini I, Douira W, Ben Becher S, Boussetta K, Bousnina S. Abdominal tuberculosis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:634-638. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Chaudhary A, Bhan A, Malik N, Dilawari JB, Khanna SK. Choledocho-duodenal fistula due to tuberculosis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1989;8:293-294. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Lazarus AA, Thilagar B. Abdominal tuberculosis. Dis Mon. 2007;53:32-38. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Shah J, Maity P, Kumar-M P, Jena A, Gupta P, Sharma V. Gastroduodenal tuberculosis: a case series and a management focused systematic review. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15:81-90. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Udgirkar S, Surude R, Zanwar V, Chandnani S, Contractor Q, Rathi P. Gastroduodenal Tuberculosis: A Case Series and Review of Literature. Clin Med Insights Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1179552218790566. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Souhaib A, Magherbi H, Yacine O, Hadad A, Alia Z, Chaker Y, Kacem MJ. Primary duodenal tuberculosis complicated with perforation: A review of literature and case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;66:102392. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Tandon RK, Pastakia B. Duodenal tuberculosis as seen by duodenoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1976;66:483-486. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Padmanabhan H, Rothnie A, Singh P. An unusual case of gastric outlet obstruction caused by tuberculosis: challenges in diagnosis and treatment. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Aljafari AS, Khalil EA, Elsiddig KE, El Hag IA, Ibrahim ME, Elsafi ME, Hussein AM, Elkhidir IM, Sulaiman GS, Elhassan AM. Diagnosis of tuberculous lymphadenitis by FNAC, microbiological methods and PCR: a comparative study. Cytopathology. 2004;15:44-48. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Gilinsky NH, Marks IN, Kottler RE, Price SK. Abdominal tuberculosis. A 10-year review. S Afr Med J. 1983;64:849-857. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Chakinala RC, Khatri AM. Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis. 2023 May 1. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Agha RA, Fowler AJ, Saeta A, Barai I, Rajmohan S, Orgill DP; SCARE Group. The SCARE Statement: Consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int J Surg. 2016;34:180-186. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |