Abstract

In order to provide more individualized support, it is imperative to further understand the effectiveness of different types of psychotherapy on the clinical areas of need common in autistic youth (Wood et al. in Behav Ther 46:83–95, 2015). Randomized controlled trials of psychotherapy for autistic youth were included if published in English, included random assignment to treatment or control group, required a previous diagnosis of autism, had a mean age of 6–17 years, and provided outcome measure data from both intervention and control groups. A total of 133 measures were coded across 29 studies and included 1464 participants with a mean age of 10.39 years (1.89). A small mean effect size (0.38,95% CI [0.26, 0.47]) was found overall, with the largest effects for cognitive behavioral therapies on autism-related clinical needs (0.81) and overall mental health (0.78). The results show the significant impact of psychotherapy interventions for autistic youth. Additional research should further assess the details of the most effective psychotherapies for each area of clinical need.

Similar content being viewed by others

Many psychotherapy interventions and supports exist for autistic youth; however, little is known about the comparative effectiveness amongst the different types of psychotherapy. The range of outcome measures utilized in intervention studies for autistic youth is also limited, as researchers have overwhelmingly focused on internalizing problems, even though psychotherapy has shown to be helpful in numerous areas of clinical need [1, 2]. The purpose of the present study is to examine the impact of different types of psychotherapy on documented areas of clinical need for autistic youth. The results from this meta-analysis can be used to make informed decisions about which types of psychotherapy to implement for specific clinical needs for autistic youth.

Autism

Autism is characterized by differences in communication and social interaction, as well as repetitive behaviors and actions and intense interests [3]. The current prevalence rate of autism in the United States is 1 in 36 children [4]. Autism is quite heterogenous as there is significant variability in the daily support needs of autistic individuals [5]. Many autistic individuals live very independent lives without support, while some autistic individuals have a few areas of support needs, and others require daily in-home support to meet their needs. The current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM–5) classifies autism on a spectrum [3].

Areas of Clinical Need for Autistic Youth

Although three main characteristics exemplify autism (differences in communication, social skills, and inflexible behavior [3]), there are multiple areas of clinical need that can be addressed in psychotherapy. Previous research has identified six main areas of potential clinical need for autistic youth: externalizing problems, internalizing problems, repetitive behavior, peer social engagement, social communication, and self-care [1, 2].

Each of the six clinical areas of need may benefit most from distinctively different forms of psychotherapy. Autistic youth with internalizing problems, such as anxiety and depression, seem to benefit from systematic desensitization [6], while autistic youth with externalizing problems, such as aggression, seem to benefit from self-management interventions [7]. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to have a positive impact on both [1, 2, 8]. Knowing which types of psychotherapy are most effective for each area of clinical need is a necessary next step in creating more individualized treatment plans for autistic youth. A similar model has been applied in school settings identifying the evidence-based practices with research linked to specific outcomes for autistic youth [9]. If researchers know which areas of clinical need different types of psychotherapy can effectively target, then that information can be used to guide treatment selection for each individual based on their unique needs.

History of Therapy for Autistic Youth

The lack of understanding of autism originally led many people to believe that it could or should be cured and many unsuccessful interventions were utilized for autistic youth [10]. Regardless of the presence of a co-occurring intellectual disability, many autistic youth were previously sent to schools for individuals who need substantial support due to intellectual disabilities, while other autistic youth were institutionalized. Only the truly wealthy received services for autism and, even then, it was focused more on management, such as reducing outbursts or repetitive behaviors, than on individual goals or positive development. Some interventions lacked evidence and others were actually damaging to autistic youth [10].

Issues with effective interventions were originally matched with issues in diagnosis. Autism can be difficult to accurately diagnose, as some individuals initially seem to show typical development and others are not detected until late childhood [11]. Improvements in diagnosis and diagnostic tools have occurred in the last decade and early diagnosis can now occur at 12 months of age [12]; however, advancements in diagnosis must be met with advancements in evidence-based interventions and supports.

Therapy and support for autistic individuals have moved away from the institutional approach and towards the unique needs of each individual. For example, CBT and behaviorally informed therapies (BITs), such as social skills training, are commonly used interventions for autistic youth. CBT has been shown to effectively reduce anxiety and depression, maladaptive behaviors, and improve self-care skills [13,14,15,16,17] and social skills training is effective in improving social competence, increasing social get-togethers, and reducing internalizing symptoms [18,19,20].

The negative history of therapy for autism highlights the need to ensure that efficacious interventions and supports are utilized and expanded moving forward. The increase in the neurodiversity movement, celebrating the natural diversity in neurotypes, has fostered an increase in autistic advocacy [21] and many autistic adults have voiced their concerns regarding certain forms of behavioral therapy [22]. Although CBT and behavioral therapies have many positive aspects, they must be consistently implemented in a respectful manner that focuses on the unique goals of each individual.

Meta-analyses of Psychotherapy for Autistic Youth

Meta-analyses have been effective in summarizing decades of intervention research into a quantifiable measure of impact that can be assessed across studies in the past, present, and future. Most notably, Weisz et al. [23] analyzed fifty years of research on psychotherapy for children and adolescents. The analyses involved 447 studies that were synthesized to discover psychotherapy has a medium effect (0.46) for youth and those who received interventions had a 63% probability of improved outcomes over the comparison group. The results of the meta-analysis by Weisz et al. [23] raise important concerns in the field of youth psychotherapy that can help guide future intervention creation and modality. Additionally, the Weisz study created a robust model for meta-analytic work in this field, including an extensive codebook for meta-analyses on psychotherapy, which was utilized in the present study.

Previous meta-analyses on interventions and supports for autistic youth have typically focused on specific types of psychotherapy. For example, Weston et al. [24] performed a meta-analysis on cognitive behavioral therapy for autistic youth, while Gates et al. [18] performed a meta-analysis on group social skills interventions for autistic youth. A recent meta-analysis examined therapies across broader domains for early intervention studies [25]. The existing research in this area does not provide a full picture of the array of types of psychotherapy interventions and supports available, nor does it provide an evaluative comparison of the impact of different types of psychotherapy. In order to fill the gap in existing research, meta-analytic studies on psychotherapy for autistic youth must be expanded to include the evaluation of the impact of each type of psychotherapy on the areas of clinical need commonly identified in autistic youth.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of the present study is to examine the evidence-base of interventions for autistic youth using a quantitative analytic approach that will synthesize the findings and ease comparison across studies. Effect sizes were computed for each of the areas of clinical need (externalizing problems, internalizing problems, repetitive behavior, peer social engagement, social communication, and self-care; [1, 2]) and types of psychotherapy (e.g. behaviorally-informed therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy). This is crucial, as the results are a quantifiable measure that can be compared across studies to examine the impact of different types of psychotherapy on each of the areas of clinical need. The results from this meta-analysis can be used to make informed decisions about interventions and supports to implement for specific areas of clinical need in autistic youth.

Research Questions

-

1.

What is the overall effect of psychotherapy for autistic youth?

-

a.

The results can be compared to the robust meta-analysis of youth psychotherapy by Weisz and colleagues [23] to see if psychotherapy tends to be overall more or less effective for autistic youth.

-

a.

-

2.

Does therapy impact differ by type of psychotherapy?

-

a.

Previous meta-analyses have included only CBT or social skills training; however, the present study will evaluate the impact across different interventions to see which types of psychotherapy are most effective and make a larger difference in the lives of autistic youth.

-

a.

-

3.

Does therapy impact differ by the areas of clinical need for autistic youth?

-

a.

Not only can more personalized goals be targeted by knowing the clinical areas of need that are significantly impacted by psychotherapy for autistic youth, but the field of autism research benefits from also knowing which areas of clinical need are currently lacking sufficient support and warrant further scientific inquiry [1, 2].

-

a.

-

4.

Does the impact of each type of psychotherapy differ for each of the areas of clinical need in autistic youth?

-

a.

Examining both the types of psychotherapy and clinical areas of need can assist in more precise treatment plans based on the needs of the individual and available interventions that effectively address those needs [1, 2]. Applying this model to the field of psychotherapy for autistic youth can potentially improve outcomes from therapeutic interventions.

-

a.

Methods

Search Strategy and Study Selection

The present study evaluated randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychotherapy for autistic youth. RCTs were chosen to identify the best-case scenario for a research base supporting the use of psychotherapy for autistic youth. Psychotherapy treatment, as defined by Weisz et al. [23], includes “an approved form of psychotherapy or psychosocial treatment (i.e., intervention designed to alleviate non-normative psychological distress, or reduce maladaptive behavior, or increase deficient adaptive behavior through counseling, interaction, a training program, or a predetermined treatment plan).”

Three search engines and databases were utilized, PubMed, PsychInfo, and ERIC. The reference sections of relevant studies were also searched for additional studies appropriate for the meta-analysis. The following keywords were searched in all combinations “psychotherapy”, “intervention”, “therapy”, “youth”, “child”, “adolescent”, “autis*”, “Asperger”, “autism spectrum disorder” and “ASD”. Articles were prescreened by trained research assistants and screened by the primary author.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria include: (a) random assignment to a treatment or comparison group, (b) a previous diagnosis or confirmed diagnosis of autism or Asperger syndrome, (c) mean age of 6 to 18 years, (d) outcomes focused on autistic youth, (e) psychotherapy as the intervention, and (f) outcome measure data collected from both the intervention and control groups. The date of publication was not limited.

Publications covering single case studies were excluded, as well as those with main outcome measures not focused on autistic youth (e.g. outcome measures focused on caregivers), and those published as dissertations. Only studies published in English were included. Additionally, pharmacological studies were excluded. Studies involving social skills group training were excluded due to the substantial body of literature on programs in that field, for example the UCLA Program for the Education and Enrichment of the Relational Skills (PEERS; [20]), and numerous recent meta-analyses that cover social skills group training (e.g. [18, 26]).

Study Coding

An extensive codebook from meta-analytic work by Weisz et al. [23] was adapted for the present study. Updates to the codebook included the addition of autism specific target problem codes that encompass autism, social communication differences, restrictive and repetitive behaviors, anxiety and autism, and emotion regulation and autism. The clinical areas of need were also added to the codebook [1, 2] along with autism-related clinical needs (e.g. measures such as the Social Responsiveness Scale) and general mental health outcomes (e.g. measures such as the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire)—due to the emergence of these areas during measure coding. Studies were coded for a subset of the variables outlined by Weisz et al. [23] and the additional autism specific target problem codes and clinical areas. Studies were coded using three separate coding sheet templates for variables related to the study, treatment and comparison groups, and outcome measures assessed.

Study Code Sheets

Variables included on the study code sheet pertain to the study methodology and participant demographics, such as the year of publication, mean age, gender, ethnicity, type of target problem, confirmation of diagnosis, single or multiple problems, and IQ score cutoff.

Group Code Sheets

A separate group code sheet was completed for each group (typically treatment and comparison) and include a description of the group, treatment code that encompasses the type of treatment or comparison group, treatment format, format of the session—individual or group, treatment integrity (pre-therapy training and adherence checks), and utilization of a treatment manual or protocol.

Measure Code Sheets

Each outcome measure with a post-treatment score for both the treatment and comparison groups was coded based on the name of the measure, clinical areas the measure covers, type of assessment, source of the rating, subject of rating, blindless of subject to the assessment, type of scores produced, scoring direction, and information related to the effect size statistic, such as the sample size, means, mean change scores, standard deviations and standard errors, when applicable.

Data Analysis

Effect Size Calculation

Given that all the measures are reported in the continuous scale, the effect size of each measure, d [27], was computed by dividing the mean difference between treatment and control group by the pooled standard deviation, \({S}_{within}\). The pooled standard deviation was calculated based on the sample size of each group, \({n}_{1}\) and \({n}_{2}\), and the standard deviation of each group, \({{S}_{1}}^{2}\) and \({{S}_{2}}^{2}\). The error variance attached to each effect size, \({V}_{d}\), is obtained from \({n}_{1}\) and \({n}_{2}\), and d [28].

where

Multi-level Meta-analytic Approach

The analysis started with several univariate models and then proceeded to more complex models. Specifically, for each target clinical area, a 3-level multilevel model was specified to account for the variation of effect sizes across studies [29,30,31]. Mean effect sizes will be reported for clinical areas with three or more measures for a given type of psychotherapy. In total, there were eight analysis models to accommodate all clinical focus areas such as externalizing problems, internalizing problems, repetitive behavior, peer social engagement, social communication, self-care, autism-related clinical needs, and general mental health outcomes.

At level-1, the observed effect size of study k for outcome j, \({d}_{jk}\), is a function of true effect size or population value, \({b}_{0jk}\), and the random deviation, \({r}_{jk}\). The random effect \({r}_{jk}\) is assumed to follow a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance \({{s}_{{r}_{jk}}}^{2}\). Typically, \({{s}_{{r}_{jk}}}^{2}\) is the squared standard error reported with effect size measure \({d}_{jk}\).

At level-2, the true effect size of study k for outcome j,\({b}_{0jk}\), is the sum of the average effect size for outcome j,\({\theta }_{00k}\), and the random effect,\({u}_{0jk}\). The random effect for outcome j is normally distributed with mean 0 and effect-size variance\({{s}_{u}}^{2}\).

At level-3, the average of all effects sizes for study k, \({\theta }_{00k}\), is the sum of the overall average across all studies, \({\gamma }_{000}\), and the random deviation of the kth study, \({v}_{00k}.\)

At level-3 in the conditional model, above, the study-level indicator of the type of psychotherapy is included. The indicator, type of psychotherapy, is dummy-coded so that the coefficients, \({\gamma }_{100}-{\gamma }_{300}\), represent the mean effect size of each category across studies. For example, if the treatment of study k belongs to the first psychotherapy, then the average of effect \({\theta }_{00k}\) is the sum of \({\gamma }_{100}\), the average effect size of CBT studies, and the random deviation, \({v}_{00k}\), \({\theta }_{00k}={\gamma }_{100}*1+ {\gamma }_{200}*0+ {\gamma }_{300}*0+{v}_{00k}\).

Given low power to detect differences and the potential for unreliable findings, moderator tests were not conducted.

Results

Study Pool

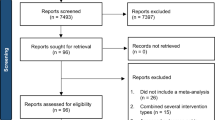

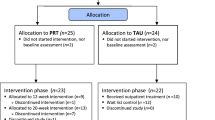

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram beginning with 2554 studies. After screening, a total of 133 measures were coded across 29 studies (listed in Table 1 and noted with an asterisk in the references) published between 2005 and 2021. One main coder independently coded all studies and 10% of studies were coded by another trained coder with an interrater agreement of 89%. The mean age of the 1464 participants is 10.39 years (1.89), with a minimum age of 7.86 and maximum of 13.39. The participants were overwhelmingly male (85%) and Caucasian (65%), although half of the studies did not report race/ethnicity. The average IQ was reported by 10 studies with a mean of 103.28 (9.17). CBT was the most common psychotherapy utilized (21 studies), then BIT (3 studies). The remaining studies were coded into an “other” category that consisted of distinctive interventions, such as therapeutic horseback riding, theatre interventions, and Lego therapy.

Posttreatment Results

The mean effect size across studies is 0.38; 95% CI [0.26, 0.47]. Table 2 presents the total estimated effect sizes for each of the clinical areas and types of psychotherapy, as well as the unique effect of each type of psychotherapy on each of the clinical areas of need with 3 or more measures per cell.

Impact of Specific Types of Psychotherapy

A similarly small effect was found for both BITs (0.49; 95% CI [0.11, 0.73]) and CBT (0.42; 95% CI [0.26, 0.53]), while other interventions (0.25; 95% CI [0.07, 0.47]) also produced a small effect for autistic youth.

Impact on the Clinical Areas of Need

As shown in Fig. 2, the impact of psychotherapy is highest in autism-related clinical needs with a medium effect of 0.70 (95% CI [0.41, 0.92]). A medium effect was also found for general mental health (0.63; 95% CI [0.18, 1.11]) and externalizing problems (0.59; 95% CI [0.19, 0.74]), while small effects were found for internalizing problems (0.43; 95% CI [0.23, 0.50]), social communication (0.28; 95% CI [0.07, 0.45]), peer social engagement (0.15; 95% CI [0.00, 0.36]), and repetitive behaviors (− 0.02; 95% CI [− 0.036, 0.41]).

Impact of Specific Types of Psychotherapy on Clinical Areas of Need

CBT has a large impact on autism-related clinical needs (0.81; 95% CI [0.50, 1.23]) and a medium impact on general mental health outcomes (0.78; 95% CI [0.43, 1.13]). BITs have a small impact on peer social engagement (0.05; 95% CI [− 0.39, 0.38]). The estimated effect sizes for other interventions were in the small range for social communication (0.28; 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.47]) and peer social engagement (0.25; 95% CI [− 0.11, 0.62]).

Discussion

What do we know about psychotherapy for autistic youth? While the present study provides insight into the impact CBT and BITs have on the areas of clinical need for autistic youth, it also highlights the need for both more precise evaluations of the types of psychotherapy and also the need for an increase in outcome measures related to adaptive skills and overall well-being. The comparable effect sizes between all youth in previous research and autistic youth in the present study suggests psychotherapy as a useful tool to increase the quality of life for all youth in need of clinical support.

Impact of Specific Types of Psychotherapy

The overall small effect found for CBT with autistic youth in the present study is comparable to the small to medium effect found in previous meta-analytic work specifically focused on CBT [24]; however, a large effect was previously reported for CBT for autistic youth with anxiety [14]. The small effect size for BITs is in line with a recent meta-analysis which also found small effect sizes for behavioral therapies in autistic children [25]. The types of psychotherapy categories were created based on the interventions utilized in the coded studies; however, the majority of studies included in the meta-analysis were CBT interventions (21 out of 29) with only a few studies in the BIT (3) and other intervention groups (5).

The three BITs included in the analyses were focused on reinforcing positive behavior through parent interactions (Parent Child Interaction Therapy by [32, 33]), teaching face processing skills using a computer-based game [34], and didactic instruction and role playing [35]. These three therapies are distinctively more behaviorally focused and include fewer or no cognitive therapy elements compared to the CBT studies in the model. Additionally, these BITs are heterogenous and have relatively little in common. In order to more accurately evaluate the types of psychotherapy, it is important to dive deeper into the interventions included in each study, especially the elements that make up each intervention.

One valuable way to assess the impact of each intervention and facilitate comparison between modalities, is by categorizing psychotherapy based on the components utilized in each intervention. Odom [36] and Wong et al. [9] assessed the literature on evidence-based practices (EBP) utilized in interventions for autistic youth in single case, quasi-, and experimental designs, and the evidence of the efficacy of each EBP on outcome variable categories. Similarly, Chorpita et al. [37] outline the benefits of understanding the evidence-based practice elements used for youth psychotherapy.

Practice elements can be thought of as the ingredients that make up the intervention [37]. Research surrounding practice elements enables more personalized therapy plans based on individual goals, demographics, and social determinants. Examples of evidence-based practice elements are: directed play, modeling, psychoeducation for both families and youth, relaxation, cognitive coping, and exposures. Expanding the work by Chorpita and colleagues to evaluate practice elements utilized in psychotherapy for autistic youth can facilitate more precise evaluation of the magnitude of the impact of psychotherapy. On an individual level, this information can help guide more precise intervention selection based on an individual's unique needs. On a population level, adopting an evaluation of practice elements approach to psychotherapy research for autistic youth can help push the field to evaluate the allocation of resources towards areas in need of further scientific inquiry.

Impact of Psychotherapy for Autistic Youth

The mean effect size of psychotherapy in autistic youth is 0.38. Weisz et al. [23] reported 0.46 from studies encompassing all youth, showing that psychotherapy is similarly as effective for autistic youth as it is for all youth. One of the major barriers to psychotherapy for autistic youth that was cited across coded studies is access to providers [38]. While many community therapists do not feel competent seeing autistic youth, those who do are often lacking quality resources for education and improvement in the delivery of services [38]. A shift in the practice of care to a more public health viewpoint—looking at disability from both a population health and individual needs perspective [39]—could increase the availability of providers for all youth. For example, the intervention manual for Schema, Emotion, and Behavior-Focused Therapy for Children (SEBASTIEN; 70) has been adapted to an online training platform that is freely available to practitioners wanting to increase their knowledge in CBT for autistic youth (Modular Evidenced Based Practices for Youth with Autism, MEYA, meya.ucla.edu).

Impact on the Clinical Areas of Need

Two additional areas were added during the coding process to the original clinical areas outlined by Wood, McLeod, and colleagues [40]. Autism-related clinical needs and general mental health areas were added to include measures such as the Social Responsiveness Scale total score (SRS; [41]) and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; [42]); respectively. The SRS was one of the most commonly used measures across all studies and overall autism-related clinical needs shows the largest effect (0.70) across all of the clinical areas. There was an unfortunate lack of measures related to adaptive functioning in the literature base. An increase in the adoption of measures of self-care skills, peer friendship and inclusion, and overall well-being would provide helpful information on the impact of psychotherapy on the daily lives of autistic youth.

Moving forward, including a stronger neurodiversity lens to the field of psychotherapy for autistic youth, especially regarding language and outcome measurement, can help decrease stigma and increase collaboration between non-autistic researchers, autistic researchers, and the autistic community [43]. Valuable resources in community participatory autism research have been produced by the Academic Autism Spectrum Partnership in Research and Education (AASPIRE [44]) and infrastructure to ease data collection and promote interdisciplinary autism research on mental and physical health from a neurodiversity perspective is under development by the Autism Intervention Research Network on Physical Health (AIR-P [45]).

Impact of Specific Types of Psychotherapy on Clinical Areas of Need

Table 2 presents the impact of each type of psychotherapy on each of the clinical areas of need. Autism-related clinical needs and general mental health have the highest effect sizes in the present study when CBT was received. The number of studies utilizing BITs and other interventions were small, thus the results must be interpreted with caution. The present results show CBT as effective in improving general mental health and decreasing autism-related clinical areas of need.

As outlined in the subsections above, important next steps in improving psychotherapy for autistic youth include using practice elements to evaluate interventions by the clinical areas of need they significantly impact and including more measures of adaptive skills focused on improving the quality of daily life for autistic youth. Improvements in these two areas would greatly increase the precision in which clinicians can measure the impact of specific methods on improving the well-being of autistic youth. This would allow for more personalized interventions to be developed based on each unique individual’s areas of clinical need and the interventions that include the practice elements most effective in improving those specific clinical areas.

Limitations and Future Directions

Codes for the different types of psychotherapy were based on the interventions described in the studies, which resulted in a CBT group, a small group of heterogenous BITs and a category of different interventions that did not fit together, nor did they fit in the CBT or BIT categories. The grouping of these categories does not produce especially meaningful results. Additional research is needed in many of the other intervention areas (theatre interventions, therapeutic horseback riding) before those studies can be meaningfully included. Additionally, while some of the clinical areas included an adequate—but still relatively low—number of coded measures, many did not; thus, full moderator analyses examining the types of psychotherapy and areas of clinical need were not feasible, and the current results are limited.

There is also a need to further evaluate the variance in each of the clinical areas to understand what is driving the mean effect sizes and if differences in impact are apparent based on the different measures used in a given clinical area or additional factors related to the specific studies or types of psychotherapy included in each clinical area of need. In order to assess the psychotherapies included in each clinical area, the studies must be examined on factors such as demographic characteristics, type of control group, therapist training, and duration of psychotherapy. This additional information would assist in the interpretation of the effect size in each clinical area of need and is an important next step.

Summary

The results of the present study highlight the utility of psychotherapy to increase the well-being of autistic youth; as well as the need for more precision in evaluating different types of psychotherapy. As the growing body of research on psychotherapy for autistic youth continues, additional inquiry is warranted on the accuracy at which interventions can be personalized for the unique needs of each individual. Considering the comparable effect sizes of psychotherapy for all youth and specifically autistic youth, improving the precision of psychotherapy interventions could increase the quality of care for all youth in need of clinical support.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, KR, upon reasonable request.

References

*Wood JJ, Ehrenreich-May J, Alessandri M, Fujii C, Renno P, Laugeson E, Piacentini JC, De Nadai AS, Arnold E, Lewin AB, Murphy TK, Storch EA (2015) Cognitive behavioral therapy for early adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and clinical anxiety: a randomized, controlled trial. Behav Ther 46(1):7–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.01.002

Wood JJ, McLeod BD, Klebanoff S, Brookman-Frazee L (2015) Toward the implementation of evidence-based interventions for youth with autism spectrum disorders in schools and community agencies. Behav Ther 46(1):83–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.07.003

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Maenner MJ, Warren Z, Williams AR, Amoakohene E, Bakian AV, Bilder DA, Durkin MS, Fitzgerald RT, Furnier SM, Hughes MM, Ladd-Acosta CM, McArthur D, Pas ET, Salinas A, Vehorn A, Williams S, Esler A, Grzybowski A, Hall-Lande J (2023) Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill Summ 72(2):1–14. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7202a1

Masi A, DeMayo MM, Glozier N, Guastella AJ (2017) An overview of autism spectrum disorder, heterogeneity and treatment options. Neurosci Bull 33(2):183–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-017-0100-y

Luscre DM, Center DB (1996) Procedures for reducing dental fear in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 26(5):547–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02172275

Koegel LK, Koegel RL, Hurley C, Frea WD (1992) Improving social skills and disruptive behavior in children with autism through self-management. J Appl Behav Anal 25(2):341–353. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1992.25-341

*Sofronoff K, Attwood T, Hinton S, Levin I (2007) A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive behavioural intervention for anger management in children diagnosed with Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord 37(7):1203–1214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0262-3

Wong C, Odom SL, Hume KA, Cox AW, Fettig A, Kucharczyk S, Brock ME, Playnick JB, Fleury VP, Schultz TR (2015) Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: a comprehensive review. J Autism Dev Disord 45(7):1951–1966. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2351-z

Thompson T (2013) Autism research and services for young children: history, progress and challenges. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 26:81–107

Fountain C, Winter AS, Bearman PS (2012) Six developmental trajectories characterize children with autism. Pediatrics 129(5):e1112–e1120. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1601

Lord C, DiLavore PC, Gotham K (2012) Autism diagnostic observation schedule. Western Psychological Services, Torrance

Drahota A, Wood JJ, Sze KM, Van Dyke M (2011) Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on daily living skills in children with high-functioning autism and concurrent anxiety disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 41:257–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1037-4

Sukhodolsky DG, Bloch MH, Panza KE, Reichow B (2013) Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with high-functioning autism: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-1193

Ung D, Selles R, Small BJ, Storch EA (2015) A systematic review and meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 46(4):533–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12021

van Steensel FJ, Bögels SM, Perrin S (2011) Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 14(3):302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0097-0

*Wood JJ, Kendall PC, Wood KS, Kerns CM, Seltzer M, Small BJ, Storch EA (2020) Cognitive behavioral treatments for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat 77(5):474–483. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4160

Gates JA, Kang E, Lerner MD (2017) Efficacy of group social skills interventions for youth with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 52:164–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.01.006

Hill TL, Gray SA, Baker CN, Boggs K, Carey E, Johnson C, Kamps JL, Varela RE (2017) A pilot study examining the effectiveness of the PEERS program on social skills and anxiety in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Dev Phys Disabil 29(5):797–808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-017-9557-x

Laugeson EA, Frankel F, Mogil C, Dillon AR (2009) Parent-assisted social skills training to improve friendships in teens with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 39(4):596–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0664-5

Kapp SK (2020) Introduction. In: Kapp SK (ed) Autistic community and the neurodiversity movement: Stories from the frontline. Springer Nature, Berlin, pp 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8437-0

Gardiner F (2017) First-hand perspectives on behavioral interventions for Autistic people and people with other developmental disabilities. Office of Developmental Primary Care, UCSF Department of Family and Community Medicine. https://autisticadvocacy.org/policy/briefs/interventions/

Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Ng MY, Eckshtain D, Ugueto AM, Vaughn-Coaxum R, Jensen-Doss A, Hawley KM, Krumholz Marchette LS, Chu BC, Weersing VR, Fordwood SR (2017) What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: a multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. Am Psychol 72(2):79–117. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040360

Weston L, Hodgekins J, Langdon PE (2016) Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy with people who have autistic spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 49:41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.08.001

Sandbank M, Bottema-Beutel K, Crowley S, Cassidy M, Dunham K, Feldman JI, Crank J, Albarran SA, Raj S, Mahbub P, Woynaroski TG (2020) Project AIM: autism intervention meta-analysis for studies of young children. Psychol Bull 146(1):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000215

Soares EE, Bausback K, Beard CL, Higinbotham M, Bunge EL, Gengoux GW (2021) Social skills training for autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis of in-person and technological interventions. J Technol Behav Sci 6(1):166–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00177-0

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Erlbaum, New York

Borenstein M, Cooper H, Hedges L, Valentine J (2009) Effect sizes for continuous data. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC (eds) The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis, 2nd edn. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp 221–235

Becker BJ (2000) Multivariate meta-analysis. In: Tinsley HEA, Brown SD (eds) Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling. Academic Press, Cambridge, pp 499–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-691360-6.X5000-9

Raudenbush SW, Becker BJ, Kalaian H (1988) Modeling multivariate effect sizes. Psychol Bull 103(1):111. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.1.111

Riley RD (2009) Multivariate meta-analysis: the effect of ignoring within-study correlation. J R Stat Soc A Stat Soc 172(4):789–811. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00593.x

Eyberg SM, Boggs SR, Algina J (1995) Parent-child interaction therapy: a psychosocial model for the treatment of young children with conduct problem behavior and their families. Psychopharmacol Bull 31(1):83–91

*Solomon M, Ono M, Timmer S, Goodlin-Jones B (2008) The effectiveness of parent–child interaction therapy for families of children on the autism spectrum. J Autism Dev Disord 38(9):1767–1776. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0567-5

*Rice LM, Wall CA, Fogel A, Shic F (2015) Computer-assisted face processing instruction improves emotion regulation, mentalizing, and social skills in students with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord 45(7):2176–2186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2380-2

*Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E, Locke J, Gulsrud A (2012) Making the connection: randomized controlled trial of social skills at school for children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53(4):431–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02493.x

Odom SL (2009) The tie that binds: evidence-based practice, implementation science, and outcomes for children. Topics Early Childhood Special Edu 29(1):53–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121408329171

Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Weisz JR (2005) Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence based interventions: a distillation and matching model. Ment Health Serv Res 7(1):5–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11020-005-1962-6

Adams D, Young K (2020) A systematic review of the perceived barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatment for mental health problems in individuals on the autism spectrum. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00226-7

Krahn G, Campbell VA (2011) Evolving views of disability and public health: the roles of advocacy and public health. Disabil Health J 4(1):12–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2010.05.005

*Wood JJ, Fujii C, Renno P, Van Dyke M (2014) Impact of cognitive behavioral therapy on observed autism symptom severity during school recess: a preliminary randomized, controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord 44(9):2264–2276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2097-7

Constantino JN, Gruber CP (2005) The social responsiveness scale (SRS) manual. Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles

Goodman A, Goodman R (2009) Strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48(4):400–403. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181985068

Bottema-Beutel K, Kapp SK, Lester JN, Sasson NJ, Hand BN (2021) Avoiding ableist language: suggestions for autism researchers. Autism Adulthood 3(1):18–29. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0014

Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, Kapp SK, Baggs A, Ashkenazy E, McDonald K, Joyce A (2019) The AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants. Autism 23(8):2007–2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319830523

Kuo AA, Hotez E, Rosenau KA, Gragnani CM, Fernandes P, Haley M, Rudolph D, Croen LA, Massolo ML, Graham Holmes L, Shattuck P, Shea L, Wilson R, Martinez-Agosto JA, Brown HM, Dwyer PSR, Gassner DL, Kapp SK, Ne’eman, A., … Kogan, M. D. (2022) The autism intervention research network on physical health (AIR-P) at UCLA: the research agenda. Pediatrics 149(Supplement 4):e2020049437D. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-049437D

*Andrews L, Attwood T, Sofronoff K (2013) Increasing the appropriate demonstration of affectionate behavior, in children with Asperger syndrome, high functioning autism, and PDD-NOS: a randomized controlled trial. Res Autism Spectr Disord 7(12):1568–1578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.09.010

*Bass MM, Duchowny CA, Llabre MM (2009) The effect of therapeutic horseback riding on social functioning in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 39(9):1261–1267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0734-3

*Chan AS, Sze SL, Siu NY, Lau EM, Cheung MC (2013) A Chinese mind-body exercise improves self-control of children with autism: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 8(7):e68184. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068184

*Gabriels RL, Pan Z, Dechant B, Agnew JA, Brim N, Mesibov G (2015) Randomized controlled trial of therapeutic horseback riding in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 54(7):541–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2015.04.007

*Gordon K, Murin M, Baykaner O, Roughan L, Livermore-Hardy V, Skuse D, Mandy W (2015) A randomised controlled trial of PEGASUS, a psychoeducational programme for young people with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56(4):468–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12304

*Keehn RHM, Lincoln AJ, Brown MZ, Chavira DA (2013) The coping cat program for children with anxiety and autism spectrum disorder: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord 43(1):57–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1541-9

*Koning C, Magill-Evans J, Volden J, Dick B (2013) Efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy-based social skills intervention for school-aged boys with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord 7(10):1282–1290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.07.011

*Maskey M, Rodgers J, Grahame V, Glod M, Honey E, Kinnear J, Labus M, Milne J, Minos D, McConachie H, Parr JR (2019) A randomised controlled feasibility trial of immersive virtual reality treatment with cognitive behaviour therapy for specific phobias in young people with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 49(5):1912–1927. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3861-x

*Owens G, Granader Y, Humphrey A, Baron-Cohen S (2008) LEGO® therapy and the social use of language programme: an evaluation of two social skills interventions for children with high functioning autism and Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord 38(10):1944–1957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0590-6

*Reaven J, Blakeley-Smith A, Culhane-Shelburne K, Hepburn S (2012) Group cognitive behavior therapy for children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders and anxiety: a randomized trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53(4):410–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02486.x

*Santomauro D, Sheffield J, Sofronoff K (2016) Depression in adolescents with ASD: a pilot RCT of a group intervention. J Autism Dev Disord 46(2):572–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2605-4

*Sofronoff K, Attwood T, Hinton S (2005) A randomised controlled trial of a CBT intervention for anxiety in children with Asperger syndrome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 46(11):1152–1160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00411.x

*Soorya LV, Siper PM, Beck T, Soffes S, Halpern D, Gorenstein M, Kolevzon A, Buxbaum J, Wang AT (2015) Randomized comparative trial of a social cognitive skills group for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 54(3):208–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.005

*Storch EA, Arnold EB, Lewin AB, Nadeau JM, Jones AM, De Nadai AS, Mutch PJ, Selles RR, Ung D, Murphy TK (2013) The effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52(2):132–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.007

*Storch EA, Lewin AB, Collier AB, Arnold E, De Nadai AS, Dane BF, Nadeau JM, Mutch PJ, Murphy TK (2015) A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and comorbid anxiety. Depress Anxiety 32(3):174–181. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22332

*Sung M, Ooi YP, Goh TJ, Pathy P, Fung DS, Ang RP, Chua A, Lam CM (2011) Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 42(6):634–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-011-0238-1

*Waugh C, Peskin J (2015) Improving the social skills of children with HFASD: an intervention study. J Autism Dev Disord 45(9):2961–2980. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2459-9

*Weiss JA, Thomson K, Burnham Riosa P, Albaum C, Chan V, Maughan A, Tablon P, Black K (2018) A randomized waitlist-controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy to improve emotion regulation in children with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 59(11):1180–1191. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12915

*White SW, Ollendick T, Albano AM, Oswald D, Johnson C, Southam-Gerow MA, Kim I, Scahill L (2013) Randomized controlled trial: multimodal anxiety and social skill intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 43(2):382–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1577-x

*Wijnhoven LAMW, Creemers DHM, Vermulst AA, Lindauer RJL, Otten R, Engels RCME, Granic I (2020) Effects of the video game ‘Mindlight’ on anxiety of children with an autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 68:11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2020.101548

*Wood JJ, Drahota A, Sze K, Har K, Chiu A, Langer DA (2009) Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized, controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50(3):224–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01948.x

*Wood JJ, Sze Wood K, Chuen Cho A, Rosenau KA, Cornejo Guevara M, Galán C, Bazzano A, Zeldin AS, Hellemann G (2021) Modular cognitive behavioral therapy for autism-related symptoms in children: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 89(2):110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.01.002

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by the health resources and services administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of health and human services (HHS) under the autism intervention research network on physical health (AIR‐P) grant, UT2MC39440, and the Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities (LEND) grant, T73MC30114. The information, content and/or conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

Funding

The authors have no funding to report for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.R. and J.J.W. led the development of the manuscript and K.R. wrote the main manuscript text; A.C. collaborated on the development of the manuscript and provided consultation and feedback regarding the research study along with A.U. and J.R.W.; J.K. and M.S. carried out and provided oversight for the data analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosenau, K.A., Kim, J., Cho, AC.B. et al. Meta-analysis of Psychotherapy for Autistic Youth. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-024-01686-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-024-01686-2