Abstract

This article is the second part of the investigation of the determinants for the uptake of Open Access (OA). While the first part focusses on journal-based OA (hybrid and full OA) (Taubert et al. in Scientometrics 128(6):3601–3625, 2023), the article at hand investigates the determinants for the uptake of institutional and subject repository OA in the university landscape of Germany. Both articles consider three types of factors: the disciplinary profile of universities, their OA infrastructures and services and large transformative agreements The article also apply a conjoint methodological design: the uptake of OA as well as the determinants are measured by combining several data sources (incl. Web of Science, Unpaywall, an authority file of standardised German affiliation information, the ISSN-Gold-OA 4.0 list, and lists of publications covered by transformative agreements). For universities’ OA infrastructures and services, a structured data collection was created by harvesting different sources of information and by manual online search. To determine the explanatory power of the different factors, a series of regression analyses was performed for different periods and for both institutional as well as subject repository OA. Given that both articles derive from the same project, there is a thematical overlap in the methods and data section. As a result of the regression analyses, the most determining factor for the explanation of differences in the uptake of both repository OA-types turned out to be the disciplinary profile, whereas all variables that capture local infrastructural support and services for OA turned out to be non-significant. The outcome of the regression analyses is contextualised by an interview study conducted with 20 OA officers of German universities. The contextualisation provides hints that the original function of institutional repositories, offering a channel for secondary publishing is vanishing, while a new function of aggregation of metadata and full texts is becoming of increasing importance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Open Access (OA) to scholarly literature has become an important and prominent way of communicating research (Robinson-Garcia et al., 2020). Recent studies show that there is a general trend towards a growing proportion of OA articles worldwide (Piwowar et al., 2018) and with exceptions also for individual countries (Bosman & Kramer, 2018), disciplines (Bosman & Kramer, 2018) and institutions (Hobert et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2020). However, this trend has multiple facets. Under the broad categories of journal-provided (or ‘Gold’) and repository-provided (or ‘Green’) OA as suggested by Suber (2012), various subtypes have evolved (Taubert et al., 2019). Two important subtypes of journal-based OA (‘hybrid OA and ‘full OA’) were studied in a previous article by the authors, which aimed to explain the difference of the uptake of OA at German universities (Taubert et al., 2023). The article at hand provides a complementary perspective as it focuses on repository-provided OA and asks for possible determinants for differences in the uptake on the level of universities, applying the same methods and data. In this publication model, repositories act as a dissemination channel besides journals, and papers may be deposited before or after acceptance in a journal. Furthermore, the type of repository on which a document is deposited can differ. The two major types are subject repositories (SR), which address a certain discipline or scientific field, and institutional repositories (IR), which refer to the members of an institution as the intended user group.

On the level of research institutions, the transition towards OA is complex as many factors may be relevant for the volume of OA that is achieved. In this study, three different types of factors are investigated: first, there is evidence that repository-provided OA has been adapted by different disciplines to a different extent and at different points in time (Bosman & Kramer, 2018; Severin et al., 2020). Therefore, the OA-affinity of the disciplinary profiles of the institution is considered as one factor. Second, there is evidence at hand that the extent to which German universities provide OA-supporting infrastructures and services differ (Kindling et al., 2021). Thus, the available infrastructural support on the level of institutions is included as a second type of factor. Third, repository-provided OA is not only achieved by actions of individual scientists that deposit their article (self-archiving) but also depends on the university's strategy that is applied for the aggregation of content from different sources (Poynder, 2016). The availability of such content depends at least to some extent on initiatives that influence the whole university landscape. In our attempt to explain repository-provided OA shares, the availability of OA content for aggregation via project DEAL and subject repositories is incorporated as a third possible factor.

The article is organised as follows: in a first step, a brief overview about the development of the repository landscape is given for both subject and institutional repositories (Sect. 2). Given that SR and IR evolved at different points in time and serve different purposes, separate hypotheses are developed for each repository type (Sect. "Research question and hypotheses"). The methods, the operationalisation of the different factors and the data collection is described in Sect. "Data and methods", followed by descriptive statistic and statistical tests of the hypotheses in Sect. "Quantitative results". The results of the analysis are contextualised with evidence drawn from 20 interviews with OA administrators from German universities (Sect. "Evidence from the qualitative interviews"). The concluding section (Sect. "Discussion") summarises the most important results.

The development of the repository landscape

The repository landscape is older than the OA movement as first experiments with preprint servers date back as early as 1991 both for physics (Ginsparg, 1994, 2011) and mathematics (Jackson, 2002). Interestingly, the initiative for the creation of such SR emanated from initiatives of the community of scholars in the two fields. Similar activities can be found in the sharing of economic literature through the REPEC network. RePEc started in 1997 and offers free online access to published and unpublished works. PubMed Central, a full text repository for articles published in medical sciences journals, was founded a few years later in 2000 (Marshall, 1999; Roberts, 2001) but differs in the way in which content is acquired. While preprint servers are fed by members of the scientific community who aim to speed up dissemination of research for different reasons or gather feedback from colleagues (Taubert, 2021), PubMed Central archives mainly already published articles in cooperation with a number of well-established life science journals. Therefore, the majority of articles are peer reviewed and not provided by authors but by journals. In more recent years, SR were populated in other hitherto unaffected disciplines by the Center for Open Science at the University of Maryland, which runs SocArXiv.Footnote 1 With the COVID-19 health crisis, discipline-specific preprint servers have proliferated to disseminate research in fields where such a practice was not previously well established (Fraser et al., 2021). Examples include medRxivFootnote 2 for health sciences and medicine and bioRxivFootnote 3 for the biological sciences, both run by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

The first institutional repositories were created in the mid-1990s and important steps were the development of the repository software OPUS (1997), EPrints (2000), and DSpace in 2002 (Lynch, 2003). From their very beginning, the aim of IRs was not as clear as for SR. Part of their proponents took SR as a role model and defined their function as providing free electronic access to publications that were published in traditional, toll access publications channels—journals in first place (Crow, 2002; Harnad, 2013). In doing so, they were understood as a reaction to the journal crisis and a means for the disruption of the journal system towards OA. A second approach defined the role of IR as a publication channel for the dissemination of all types of intellectual products from research and teaching (Lynch, 2003) that were usually excluded from the traditional publication channels. Such products include grey literature, technical reports, working papers, theses, dissertations, video and audio recordings, research instruments and protocols as well as datasets and software (Kennison et al., 2013). However, both visions of IR have the common ground that faculty should get involved in the usage of the IR by the provision of content via self-archiving.

Regarding the development of the repository landscape, a number of studies show that a wave of IR was established in the middle of the first decade of the millennium in many countries (Pinfield et al., 2014). In some countries, the development started earlier: in 2005, Australia, Norway, the Netherlands, and Germany already showed large numbers of IR compared with the number of universities, leading to the assumption that a good provision of such services was already in place (van Westrienen & Lynch, 2005). A strong development towards a diversified institutional repository landscape was also observed in the same year for the US (Lynch & Lippincott, 2005). Since 2011, Pinfield et al., (2014) report a plateaued growth for the UK and the Netherlands, indicating a saturation, while the growth of Germany`s repository landscape tended to be slower and more sustained during that time. After a critical discussion of the shortcomings of the respective OA evidence systems (OpenDOAR and ROAR), Arlitsch and Grant (2018) estimate the number of repositories world-wide to be as large as 3,000–3,500 for 2018. Since then, the growth in numbers seems to continue. At the time of writing, OpenDOAR lists 5,995 repositories, of which a small minority of only 375 are SR while the large majority of 5,311 are IR.

Besides the sheer quantity of the repositories, some studies are interested in the role that IR and SR play in the communication system of science and we would like to mention four results here: first, there is some evidence of disciplinary differences in the adoption of repository-provided OA (Archambault et al., 2014; Björk et al., 2014; Kling & McKim, 2000; Martín-Martín et al., 2018; Pölönen et al., 2020). Second, such differences can be found for SR but are also observed for IR (Pinfield et al., 2014). Third, whenever scientists are motivated internally to self-archive, SR are often preferred to IR (Spezi et al., 2013). In contrast, when self-archiving is mandated, IR are used more often for the deposition of articles. Fourth, scholars who are familiar with self-archiving in a SR do not necessarily self-archive on IR. “Instead, evidence reveals that when an article has been presented in one repository, the author(s) will be hesitant to make it repeatedly available in a second repository” (Xia, 2008, p. 494). In other words, the result suggests a rivalry between SR and IR for authors that self-archive their publications.

The last aspect we would like to mention refers to IR only: the review of the literature reveals that the aim of IR was not only controversial at the beginning but was also altered and redefined along the way of its development. This dynamic was in part driven by the development of web technology and the availability of data, and in part the result of changing priorities of university management. However, one important condition for the continual redefinition of aims are complaints about the low usage of IR for the deposition of content since their origins (Arlitsch & Grant, 2018; Nicholas et al., 2012; Novak & Day, 2018; Westrienen & Lynch, 2005; Xia, 2008). The first and obvious reaction to low usage was to sustain the aim of IR to provide free access to electronic content (however defined) but to attribute the responsibility for the deposition in a new way. Even though self-archiving is still an option in many IR, the content was more and more uploaded by library staff on behalf of the scientists. In other words, self-archiving was increasingly replaced by ‘mediated archiving’ (Xia, 2008). According to an interview study conducted in 2011, the majority of faculty from medical and life sciences as well as authors from social sciences and humanities report that someone else deposited their publication in an IR (Spezi et al., 2013).

A second and more far reaching step in the direction of a re-definition of aims is undertaken when IR-provided OA is linked to research evaluation. In the prominent case of the University of Liège, OA is mandated and the IR is used for the provision of data on which internal research evaluation (for tenure and grant proposals) is based (Rentier & Thirion, 2011). In this case, the requirements of research evaluation are piggybacked on the original aim of providing access to faculties’ intellectual work.Footnote 4 The confutation of IR with (Current) Research Information Systems as suggested by Dempsey (2014) and Plutchak and Moore (2017) points in the same direction. The collection, enrichment, and synchronisation of metadata like the information about the organisational structure of the institution, ORCID identifiers for authors, Altmetrics, and citation information do not support free access to content in the first place but serve the need for monitoring, evaluation, and reporting of the university management (Novak & Day; Zervas et al., 2019). It is a matter of fact that such an aim does not necessarily need full texts but a collection of valid and well curated metadata to be fulfilled.

-

For the purpose of our study, we define the two repository-provided types SR OA and IR OA as follows: Subject repository OA (SR OA) identifies all types of scholarly output for which a version is available on a repository that is used by a certain discipline or field (e.g. arXiv, RePEc, PubMed Central, medRxiv, bioRxiv, and SocArXiv). Such versions may be preprints (i.e. a version of a publicationthat has been made available before acceptance) or postprints (i.e. a version of a publicationthat has been made available after acceptance in a journal).

-

Institutional repository OA (IR OA) identifies all types of scholarly output for which a version is available on a repository run by a university or a research organisation. Again, such versions can include pre- as well as postprints.

For reasons of practicality (see Sect. "Data and methods" ‘Data and Methods’), the analysis is restricted to the publication type ‘article’.

Research question and hypotheses

Previous research has pointed to large differences regarding the uptake of OA on the level of institutions (Hobert et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2020; Robinson-Garcia et al., 2020). Complementary to a paper that focuses on journal-based OA (Taubert et al., 2022), this article aims to answer the question of what factors determine repository-provided OA shares (SR OA and IR OA) of German universities. The uptake of OA can be influenced by a number of factors. These may include the disciplinary profile of the universities,Footnote 5 OA infrastructures and services that are intended to support OA, OA policies on the local level, the amount of third-party funding and OA mandates that require OA to publications of funded projects or, the participation in large competitive funding programs like the German universities’ Excellence Initiative, in which previous research output has to be documented.Footnote 6 The selection of the factors considered in the analysis was driven by the availability of data. Given that the German university landscape consists of 104 universities at the time of data collection, it was critical to collect data with nearly complete coverage of the university landscape in order to keep the number of cases high enough to perform the regression analyses. In the end, three factors are considered in the models: these are the disciplinary profile of the universities, their local infrastructures and services and transformative agreements. Disciplinary profile: The first type of factor that may determine the OA profile of a university is its disciplinary profile or, in other words, the specific mixture of scholarly outputs in different disciplines, specialties and fields. It is generally known that disciplines share specific publication cultures, communicate via a set of field-specific publication media that are subject to generalised quality attributions of the respective scientific community on which a reputation pyramid of the publication media is based, as well as convictions about standards that publishable research has to meet together with mechanisms that apply such criteria to select contributions for publication (e.g., peer review). Another component are field-specific routines or practices on how to deal with scientific information that is made available via different channels. Publication cultures also comprise attitudes towards different OA-types resulting in differences regarding the OA-affinity (Dalton et al., 2020; Zhu, 2017) also with respect to repository-provided OA (Björk et al., 2014; Kling & McKim, 2000; Pinfield et al., 2014; Pölönen et al., 2020).

Local OA infrastructures and services a second type of factor that may be relevant for the uptake of OA are infrastructures that are accompanied by services and staff and provided locally by universities. The rationale behind such infrastructure is to offer means to publish research OA and to reduce the related efforts for scientists. With regard to repository-provided OA, local infrastructures and services include IR for depositing (and aggregating) research. Moreover, some universities introduced positions like OA officers that should support scientists, OA websites that inform about the topic as well as OA events and training activities that aim to raise the attention and to teach the necessary competencies. With respect to rules and regulations that support OA, the German situation is special: given that freedom of science is guaranteed by the German constitution (Art. 5 III Grundgesetz), and given that the publication of research is protected by this right, there are no mechanisms of strong top-down regulations on the level of universities like, for example, mandates that enforce repository-provided OA.Footnote 7 However, a number of universities have given themselves an OA policy, which expresses the university leaders’ support and ‘encourages’ scientists of the institution to make their publications freely available online. For the German university landscape, mapping instruments (Kindling et al., 2021)Footnote 8 show that there are remarkable differences of OA infrastructures and services at different locations.

Transformative agreements in recent years, transformative agreements have been introduced, and the probably most impactful contracts are those that were negotiated between large publishing houses and project DEAL.Footnote 9 Given that they operate on an ‘all-in-principle’ of nearly all public research institutions to date, the contracts can be regarded as a central coordination mechanism that affects the entire German research system. Such instruments are in the first place means to turn publications at the publishers’ venue into OA (Haucap et al., 2021) as they make all publications from a member institution in the portfolio of a publisher freely available online while offering access to the whole content of a defined set of journals from a publisher to member institutions. Such contracts create a large stock of publications that are OA and hence can also be used for the aggregation of content in repositories (Taubert et al., 2023). Therefore, transformative agreements may also affect the OA share of a university that is available via repositories.

Subject repository OA

After having explained the three factors in more detail, we formulate the following hypotheses regarding their influence on the subject repository OA share of universities.

SR-1: Hypothesis on the influence of the disciplinary profile

Footnote 10

H1: Universities with a disciplinary profile that shows a strong affinity towards SR OA have a larger SR OA share than universities with a weaker disciplinary affinity towards SR OA.

H0: Universities with a disciplinary profile that shows a strong affinity towards SR OA have a smaller (or equal) SR OA share than universities with a weaker disciplinary affinity towards SR OA.

SR-2: Hypothesis of the impact of local infrastructures and services

Footnote 11

H1: Universities with extensive OA infrastructures and services have a larger SR OA share than universities with less elaborated infrastructures and services.

H0: Universities with extensive OA infrastructures and services have a smaller (or equal) SR OA share than universities with less elaborated infrastructures and services.

OA officer, websites with OA (rights) information and/or OA training activities

SR-3: Hypothesis on the impact of transformative agreements Footnote 12

H1: The larger the share of the publication output covered by transformative agreements, the smaller is the SR OA share of German universities.

H0: The larger the share of the publication output covered by transformative agreements, the larger (or equal) is the SR OA share of German universities.

Institutional repository OA

The following six hypotheses are inspired by the overriding assumption that the IR OA share is predominantly determined by organisational factors and, in particular, infrastructural support.

IR-1: Hypothesis on the influence of the disciplinary profile

Footnote 13

H1: Universities with a disciplinary profile that shows a strong affinity towards IR OA have a larger IR OA share than universities with a weaker disciplinary affinity towards IR OA.

H0: Universities with a disciplinary profile that shows a strong affinity towards IR OA have a smaller (or equal) IR OA share than universities with a weaker disciplinary affinity towards IR OA.

IR-2: Hypothesis on the impact of local infrastructures and services

Footnote 14

H1: Universities with extensive OA infrastructures and services have a larger IR OA share than universities with less elaborated infrastructures and services.

H0: Universities with extensive OA infrastructures and services have a smaller (or equal) IR OA share than universities with less elaborated infrastructures and services.

IR-3: Hypothesis on the aggregation of OA publications covered by transformative agreements

Footnote 15

H1: The larger the share of the publication output of a university covered by transformative agreements, the larger is the IR OA share (as university libraries find more OA publications from transformative agreements that can be aggregated in their IR).

H0: The larger the share of the publication output of a university covered by transformative agreements, the smaller (or equal) is the IR OA share.

Data and methods

This section provides a brief description of the methods and data of this study. For a more detailed presentation of the methods, see Taubert et al., 2023.

Both, the first part of the study on journal-based OA (Taubert et al., 2023) and the article at hand on repository-based OA derive from the same project and are based on the same data and methods. Therefore, there is a thematical overlap between the two papers. The analysis is grounded on three types of empirical data: bibliometric data of the publications of German universities including evidence of OA, structural data of German universities and information about OA infrastructures that are provided by them, as well as interviews with 20 OA representatives and officers from German universities.

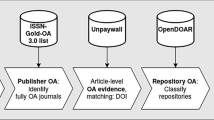

Regarding the first type of data, the publication output of German universities is determined by the Web of Science, including evidence OA from different sources.Footnote 17

Given that both IR OA and SR OA can be achieved via self-archiving and given that all authors of a publication can in principle perform such activity, the publication output of a university was defined as publications with at least one author with an address from the particular German university. The analysis covers all publications from the years 2010–2020 with at least one author affiliated to a German university. An article was classified as repository-based OA if Unpaywall’s field ‘host type’ reported that a version of the article was in a repository. Given that Unpaywall does not further distinguish between different types of repositories, domains from repository full text links were extracted from Unpaywall and matched with the Directory of Open Access Repositories (OpenDOAR), a comprehensive registry of repositories supporting the OAI standard. Using the OpenDOAR repository classification, we distinguished between institutional, discipline-based, and other types of repositories. If a domain was not listed in OpenDOAR, repository full-texts were classified as “other”. For the further analysis, only articles in IR and SR were considered. For the disciplinary profile of German universities, a highly aggregated factor was calculated. For each of the 255 WoS subject categories, subject category-specific OA shares were computed based on all publications with an author from a German research institution. Based on the number of publications of a university in each of the subject categories and the OA shares of the categories, a disciplinary influence factor was generated for all universities and for both SR OA (\({X}_{1}^{SR}\)) and IR OA (\({X}_{1}^{IR}\)), namely

where

\({X}_{1}^{SR}\left(i\right)\) SR OA disciplinary influence factor for university \(i\in I\) the set of all included universities,

\({X}_{1}^{IR}\left(i\right)\) IR OA disciplinary influence factor for university \(i\in I\),

\({N}_{i,s}\) Number of publications of university \(i\in I\) in WoS subject category \(s\in S\) the set of all WoS subject categories,

\({T}_{i}\) Total number of publications of university \(i\in I\),

\({P}_{s}^{SR}\) SR OA share of WoS subject category \(s\in S\), and

\({P}_{s}^{IR}\) IR OA share of WoS subject category \(s\in S\).

The disciplinary influence factor considers publications in all WoS subject categories regardless of whether they show strong, average or weak SR/IR OA adoption. It can be understood as an expectancy value of a university SR/IR share in knowledge of the composition of the disciplinary profile.

Given that regression analyses were performed for three different periods (2010–2020, 2017–2018 and 2020), disciplinary influence factors were calculated for each period.

For local infrastructures and services, a structured data collection was createdFootnote 18 by harvesting the GEPRI database,Footnote 19 ROARmap,Footnote 20 Bundesländeratlas Open Access (Kindling et al., 2021). Moreover, we performed a manual web search. In our model, the data act as reposed variables \({X}_{2}\) to \({X}_{8}\) (see Table 1).

Transformative agreements were considered as a third factor. Its operationalisation is based on available data about the agreements between project DEAL, on the one hand, and Wiley and SpringerNature, on the other. Both contracts operate on an all-in principle and were signed by German universities. However, the number of publications covered by the two contracts differs and varies from university to university. In the analysis, the influence of the DEAL contracts are considered for the year 2020 as this is the only year for which the transformative agreements have been effective throughout the year and for which data are available.Footnote 21 For operationalisation, the share of the publication output covered by DEAL contracts were determined for each university as

where

\({X}_{9}^{D}\left(i\right)\) Share of OA publications covered by DEAL contracts for university \(i\in I\), the set of all included universities,

\({D}_{i}\) Number of OA publications covered by DEAL contracts for university \(i\in I\),

\({T}_{i}\) Total number of publications of university \(i\in I\).

Table 1 provides an overview of the explanatory variables that are considered in the regression analyses.

For the purpose of putting the explanatory models into a broader context and to gain more insights on how the three factors interact with the uptake of OA on the local level, we conducted 20 expert interviews with OA officers from different German universities. The selection of the interview partners followed the selection scheme of maximum variation (Collins et al., 2006, p. 84) and included interviewees from small and large universities, universities with strong and weak adaption of OA and with different disciplinary foci. All interviews took place between February and June 2021 and, with respect to the topics, covered all factors that were included in the regression models. The duration of the interviews ranged from 47 up to 119 min. For the preparation of the analysis, all interviews were transcribed by a transcription service and analysed with content analysis (Mayring, 2015). For this purpose, we used MAXQDA data analysis software and developed a code tree with 166 different codes. All interview transcripts were fully coded, resulting in 3,118 paragraphs that were assigned to the codes.

Quantitative results

Descriptive statistics

Given that the findings reported in this section are also part of the first analysis (Taubert et al., 2023), a condensed overview will be given. To begin with, descriptive statistics are reported for categorical (Table 2) and metrical (Table 3) independent variables, followed by publication-based information (Table 4). Please note that the characteristics and availability of information differ. Information about infrastructures at German universities were collected at a certain point and will be subject to change over time. The same holds for repository-based OA shares of German universities and disciplinary influence scores as publications may be deposited on a repository retrospectively (or removed from them). Information about the DEAL contracts is available for the year 2020 only.

Table 3 provides descriptive statistics for the duration (in months), in which OA policies are effective. In the first line, universities without OA policies are included (0 months of effectiveness of OA policies), while the second line is limited to universities with OA policy only.

In Table 4, the descriptive statistics are presented for the publication-based variables. For all of the three periods, the table includes SR and IR OA shares, SR and IR OA disciplinary influence factors and total numbers of publications. Due to availability of data, a DEAL influence factor is calculated for 2020 only. To avoid distortions due to small numbers of publications, all indicators are calculated for universities that exceed the threshold value of 50 publications in the respective period. The results in the table show that all OA shares have increased for more recent years and for both repository-based OA types. The growth of the share for both types happens roughly at the same scale, while the standard deviation is larger in the case of SR OA when compared with IR OA.

Regression models

In this section, we present the results of the regression models. Multiple linear regression analysis is a popular statistical method that can be used to text hypotheses about relations of data. Thereby, the variation of the output variable, named dependent variable, shall be explained by one or more input variables, named independent variables, which are assumed to have effects on the dependent variable. In our analysis, we performed separate regression models for the three periods and two dependent variables each—the SR and IR OA share of German universities. Given that collinearity of independent variables is a problem in regression analysis, variance inflation factors (VIF) were calculated in order to detect it. Again, VIF were computed for all three periods and for both OA types.

The values in Table 5 show that there is some explanatory power between the independent variables, but they all are well below the critical value of 5 that is considered as a threshold value above which the model should be adjusted, e.g. by excluding or modifying certain independent variables. As a consequence, all considered variables are included in the regression analysis (Tables 6, 7).

A first look at the results of the regression analyses reveals that the uptakes of the two types of repository-based OA follow different patterns. To begin with subject repository OA, the only factor that is significant and that has strong explanatory power for each of the three periods is the disciplinary influence factor. According to Adj. R2 for the period 2010–2020, it explains 93.2% of the variance of the subject repository OA share of German universities, and for more recent periods the share is on a similar level (91.6% for 2017–2018 and 92.4% in 2020). For SR-1 (“Universities with a disciplinary profile that shows a strong affinity towards SR OA have a larger SR OA share than universities with a weaker disciplinary affinity towards SR OA”), the null-hypothesis is therefore rejected, meaning that the disciplinary profile of a university has a strong influence on the SR OA share. Regarding the variables that operationalise local infrastructures and services, none of them turned out to be significantly different from zero. This holds for OA policies, as well as the existence ofOA officers, websites with OA (rights) information and/or training activities. In other words, the existence of local infrastructures and services does not affect the subject repository OA share. The influence of transformative agreements could only be tested for the period 2020. SR-3 “The larger the share of the publication output covered by transformative agreements, the smaller is the subject repository OA share of German universities”) suggests a possible de-incentivising effect for the deposition of articles on subject repositories which may result from the fact that such publications are already OA in the publisher version. Given that the coefficient of the DEAL influence factor is not significantly different from 0, the null-hypothesis cannot be rejected, casting doubt on the relevance of such an effect. To summarise, the regression models provide evidence that differences in the SR OA share of German universities result from the composition of the disciplinary profile with their specific OA affinity, but there is no evidence for an influence of any of the other variables that are considered here.

Compared with SR OA, the regression models for IR OA are somewhat more heterogeneous and a bit more difficult to interpret: for all of the three periods, the disciplinary influence factor is again the independent variable with the strongest explanatory power and it is also highly significant. As a result, the null-hypothesis of IR-1 (“Universities with a disciplinary profile that shows a strong affinity towards IR OA have a smaller (or equal) IR OA share than universities with a weaker disciplinary affinity towards IR OA”) is rejected, implying a strong influence of the disciplinary profile. However, two additional aspects are worth noticing. First, the variance explained by the disciplinary influence factor is considerably lower for IR OA (reg. 9, 11, 13) than for SR OA (reg. 2, 4, 6). Second, the explained variance is large for the period 2010–2020 (adj. R2: 0.412) and 2017–2018 (adj. R2: 0.489) and is strongly shrinking in 2020 (adj. R2: 0.131). These results point to a decreasing relevance of the disciplinary profile as an explanation of the IR OA share for the last year that is considered in the analysis.

With respect to IR-2 (“Universities with extensive OA infrastructures and services have a larger IR OA share than universities with less elaborated infrastructures and services”), the results for the different variables have to be interpreted individually. First, the regression coefficients for variable \({X}_{2}\) (existence of an institutional repository) do not differ from 0 significantly. This result indicates that the existence of an institutional repository increases the IR OA share. This finding is in line with the assumption of Giesecke (2011) that the mere existence of an IR is not sufficient to provoke self-archiving. Regarding OA policies, the regression coefficients for \({X}_{7}\) and \({X}_{8}\) are not significantly different from 0 in regressions no. 7, 10 and 12, indicating that universities with an OA policy do not have larger IR OA shares than universities without such OA supporting instruments. The same holds for the variables existence of an OA officer, websites with OA (rights) information and/or OA training activities. In all periods analysed here, the corresponding variables X4 to X8 turned out not to be significantly different from 0. Regarding the hypotheses on the effects of aggregating activities at libraries (IR-4 “The larger the share of the publication output of a university covered by transformative agreements, the larger is the IR OA share”) the null-hypotheses cannot be rejected for any of the periods, thus indicating that this factor does not play a role. The SR OA share as a possible resource for the aggregation of content in institutional repositories turns out to be significant but only for the period 2010–2020. Here, the coefficient of the SR OA share \({Y}_{S}\) is significantly different from 0 on a 0.01-level adding 7.0% explained variance to the model. With tolerable probability of error, a higher availability of publications on subject repositories seems to increase the IR OA share in the period 2010–2020.

Evidence from the qualitative interviews

In this step, the results of the regression analyses are discussed in the context of findings in the literature as well as results of interviews with 20 OA administrators from German universities that were conducted within this study.

Subject repositories

To begin with subject repository OA, the results show that the disciplinary profile is the most determining factor for the understanding of differences in this OA type. In other words, the adoption of SR OA happens in the first place within certain disciplines and specialties, and the SR OA share of an institution reflects the disciplinary profile and its composition with fields that have more or less affinity towards SR OA. This finding is in line with the observations of the large majority of the interviewees that report large differences between different disciplines in the extent to which self-archiving on SR takes place. One example is interviewee I-05 who describes the situation of such differences between disciplines as follows:

Given that it has developed in principle in high energy physics, actually since the internet came into existence and has spread a little in neighbouring disciplines, takes all physics and mathematics on top. You can see that they were used to doing such things. And it is the same with economics. There have always been discussion papers that circulated, where preprints were established and this has been transferred into the electronic world. In other cases, such predecessors are missing to some extent. (I-05, pos. 53)Footnote 22

Other interviewees also point to long-standing traditions in the publication culture of certain fields with stable patterns of exchange of preprints and working papers.Footnote 23 Mechanisms stabilising such type of exchange that were addressed in the interviews are the combination of a better findability and accessibility for scientists in the role of the readerFootnote 24 and better visibility of their own research and a means to increase reputation for scientists in the role of the author.Footnote 25 Such complementary patterns in the use of preprint servers are involved in some (Taubert, 2021) but not in all disciplines, as studies on the usage of SR show (Björk et al., 2014; Kling & McKim, 2000; Pinfield et al., 2014). An additional argument put forward by two interviewees that may help to explain disciplinary differences in the adoption of SR OA is that the deposition of preprints on SR is also a means for speeding up the circulation of new findings (I-07, pos.9, I–15, pos. 71). However, speed of circulation may not be of similar relevance in all disciplines and fields.

With respect to SR, one interesting aspect is that a number of intervieweesFootnote 26 report that they do not know much about the self-archiving on SR of scientists from their institution and often do not regard themselves as being competent to answer the questions on SR. The reason for this becomes visible in the following quotation from the interview with I-16:

I don’t know much about it. By coincidence I notice that some papers that are funded by our publication fund have been self-archived by natural scientists on arXiv. This is what I notice sporadically. Well, regarding the social sciences and humanities, I do not notice anything because we do not have a working bibliography for our university and because they rarely use our publication fund. Therefore, I cannot say much about it. (I–16, pos. 43)

OA administrators are often not aware of the self-archiving activities from scientists of their university as they are responsible for a certain set of OA services like the provision of a publication fund or the operations of a publication platform or an IR. A number of interviews suggest that the responsibilities of OA administrators are not directed towards the increase of OA based on SR in the first place and that they only get in contact with this OA type when native OA services of the university—like publication funds in the quotation above—are involved. This orientation towards own services may explain in part why the variables that operationalise local infrastructures and services do not play a role for the explanation of the differences of the SR OA share, as they do not focus on this OA type at many universities.

Institutional repository OA

Compared with SR, the results of the regression models for IR are less outstanding, but a solid share of the variance of the IR OA share is explained for the two periods 2010–2020 and 2017–2018 by the disciplinary influence factor. In 2020, there is a remarkable decrease down to 13.1% of explained variance. Again, the variable of local infrastructures and services do not add explained variance to the model while the ‘SR OA share’ adds 7.0% of explained variance for the period 2010–2020 only. These results provoke two questions: first, what are the reasons for the substantial decrease of the explanatory power of the regression model in the most recent year? Second, why is the explanatory power of the variables of local infrastructures and services that low?

Regarding the first question, the results of the regression analysis for 2020 suggest that the main factors for this period are not included in the model and that a change happened between the period 2017–2018 and 2020. Fortunately, the interviews provide some evidence of a factor that became relevant in recent years. To understand this change, it is key to note that the diagnosis of a low usage that has accompanied IR for more than 15 years (Arlitsch & Grant, 2018; Nicholas et al., 2012; Novak & Day, 2018; Westrienen & Lynch, 2005; Xia, 2008) is also reflected in the interviews of this study. No less than 13 intervieweesFootnote 27 state phrases like the amount of self-archiving is ‘very little’ (I-04, pos. 30), ‘very, very, very low’ (I-20, pos. 25), or ‘could definitely be more’ (I-15, pos. 49), and that the activities of the scientists on IR are below their expectations. Two responses to low usage can be found in the interviews. One is to provide ‘value-added services’ to incentivise self-archiving. Examples are the possibility to create personal or project-specific publication lists for different purposesFootnote 28 or the integration of the Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID) and metadata exchange with this service. The other one consists of a large diversity of activities of libraries that aim to collect or aggregate publications of researchers from their institution in the IR that can be summarised under the term ‘mediated archiving’ (Xia, 2008). Such activities often happen autonomously by the operators of the IR without any consent of the authors being necessary. In 14Footnote 29 of the 20 interviews, such activities were characterised as a strategy besides self-archiving to fill repositories with content. Sources for full texts to be deposited by libraries in IR are diverse and can be assigned to two types: on the one hand, there are non-OA sources. In these cases, archiving on IR is a means to make a publication OA. Examples are the project DeepGreen with its original aim to operate as a data hub that automatically collects full texts and metadata of publications from publishers for which secondary publication is permitted by, for example, national licences to operators of IR for automatic depositing (Boltze et al., 2022). According to the project website,Footnote 30 German universities used this service at the time of writing, and it is also mentioned as a source of content for IR in a number of interviews.Footnote 31 Universities also use their subscription licences that include self-archiving rights for the institutions’ authors to deposit their publications on the IR. On the other hand, the interviewees mention a number of sources for aggregation where the content is already OA. These include SR,Footnote 32 publications in full OA journals paid by the university’s publication fund,Footnote 33 publications in journals of OA publishers,Footnote 34 as well as publications made OA by transformative agreements.Footnote 35 The use of such data sources can be understood as a remarkable shift of the original aim of IR to increase OA to the universities’ intellectual output. One interviewee describes this development as follows:

Well what we do is, we put everything on [Name of IR, anonymized] what is funded via our publication fund or via DEAL or via other transformative agreements. But this is redundant because these are primary Gold OA publications. They can also be found on [Name of IR, anonymized] and we can say ‘Look at all the nice things we have funded’. But it is a type of secondary publishing or archiving but not in a way that something becomes accessible that was formerly behind a paywall. (I–16, pos. 33)

In this context of use, the deposition of content that is already OA on IR can be understood at best as a strategy of archiving that guarantees OA articles to stay OA in a publishing environment which bears the risk that certain journals may vanish (Laakso et al., 2021) or as an attempt to create legitimation for a repository that is rarely used by researchers. The re-definition of the role of IR, however, does not stop here and reaches beyond the deposition of full texts. A number of intervieweesFootnote 36 report that IR are used for the aggregation of metadata. In this context, the designated use of IR has shifted from an infrastructure that aims to support the supply of information within the scientific community to the information requirements of the universities’ management.

Coming back to the first question about the decreasing explanatory power of the regression models for more recent years, evidence from the interviews support the assumption that important factors are not considered in the models. These may include the myriad ways in which university libraries collect and aggregate content from manifold sources in their IR. Many of these sources originated and became usable during the last few years, such as DeepGreen, which disseminated its service from 2018 onwards, the transformative agreements with project DEAL, which became effective from 2020Footnote 37 onwards, or also the publication funds that were created during the last years at many universities.

Discussion

Complementary to a previous publication on journal-based OA, this article aims to investigate the determinants of repository-provided OA. To the best of our knowledge, our analysis is the first that moves from a bibliometric description of the uptake of OA (Hobert et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2020; Robinson-Garcia et al., 2020) towards an explanation by considering multiple factors. However, and like any other empirical studies, our analysis has a number of limitations and we will discuss the three most important ones. A first limitation refers to the factors that were included in the regression models. Even though the disciplinary profile of universities turned out to be a relevant factor for both types of repository-provided OA and for all periods, the unexplained variance of the dependent variables suggests that there are other determinants that were not considered in our analysis. This in particular holds for the IR OA share in more recent years. Aside from the aggregation activities of providers of IR that were already discussed, the local usage or integration of IR in current research information systems (CRIS) as well as the share of publications that emanated from third-party-funding subjected to OA mandates may be possible candidates. While the first factor was beyond our imagination at the conception of the study, the second factor could not be included because of lack of data. Data were only available for parts of the German university landscape, and an inclusion of the factor would have resulted in a severe decrease of the number of cases.Footnote 38 For other countries, it would be interesting to see if third-party-funding turns out to be a significant factor in follow-up studies. In addition, some variables of local infrastructures and services could have been operationalized in greater detail. Against the background of the interviews, this in particular holds for the existence of an IR, OA administrator, website with OA (legal) information, and OA training activities. For further research, it is probably more suitable to ask for more detailed information with respect to the collection and aggregation of published research that are undertaken by libraries, the data sources that are used and the manpower that is applied for this task than for supporting infrastructures and services that refer to self-archiving.

A second limitation refers to the way in with the disciplinary profile is operationalized and measured. The disciplinary influence factor is conceptualized on a high level of aggregation that comprises all publications of the universities in all respective periods and in all of the 255 WoS subject categories. While the advantage of the operationalization is obvious (measuring the disciplinary profile with a single number), the drawback is also apparent: information about what subject fields contribute to a high or low OA share of universities are hidden by the level of aggregation. Given that the disciplinary influence factor turned out to be the most important one for the understanding of the OA share of institutions, it seems to be promising to de-aggregate the factor and to investigate what subject categories contribute the most.

The third limitation refers to the selected field of investigation, i.e. the German university landscape. This focus was intentionally chosen as universities are organizations that always include a mixture of different disciplines and fields. Given that other non-university research institutions in Germany as well as universities in other countries operate under different conditions and OA governance varies in different countries, the results cannot be easily generalized to other countries or other types of research institutions. Therefore, there is a need for similar studies in different countries and for different types of research institutions. After having expressed basic limitations that stand against a simplistic generalization of the results of this study, some careful expectations can be made regarding further empirical studies on this topic. Given that the disciplinary influence factor is the most important determinant for both SR and IR OA and for all periods, and since a number of studies report that the uptake of OA differs between different disciplines and subject fields (Bosman & Kramer, 2018; Piwowar et al., 2018; Severin et al., 2020), we have very good reasons to believe that the factor may also play a relevant role in other countries and for other types of research institutions. With respect to other factors, we expect different results. This in particular holds for the role of open access requirements. Germany is characterized by a virtual absence of open access mandates that require OA, and strong OA mandates have turned out to be a crucial factor that promotes self-archiving. To be more precise, we expect that OA mandates may in particular enhance the OA share in the repository infrastructure of the mandator, which are in the first place institutional repositories (Gargouri et al., 2012; Vincent-Lamarre et al., 2016; Larivière & Sugimoto, 2018; Kirkmann & Haddow, 2020).

Conclusion

The aim of this article is to answer the question as to what extent the disciplinary profile, local infrastructures and services and transformative agreements of the project DEAL determine the repository-provided OA share of German universities. The results show that the two repository OA types, subject repository OA (SR OA) and institutional repository OA (IR OA), follow different logics. Therefore, the question has to be answered separately for each of them. Regarding the SR OA share of universities, the regression analyses convincingly show that the composition of the disciplinary profile with a stronger or lesser affinity towards OA is decisive and explains as much as 93.2% of the variance for the period 2010–2020. For more recent years, the importance of the disciplinary profile is on the same level with an explained variance of 91.6% for 2017–2018 and 92.4% for 2020. This result highlights that the adoption of SR is in the first place driven by the inner logic of scientific publication cultures, which is in this context referred to as the disciplinary profile. All other factors like infrastructural support do not help to understand differences of the SR OA share of institutions.

With respect to the IR OA share, the composition of the disciplinary profile is again the most determining factor, but the explained variance is lower than in the case of IR OA. For the period 2010–2020, the disciplinary influence factor explains 41.2%, and for the period 2017–2018, 48.9% of the variance of the universities IR OA share. Variables that operationalise local infrastructure and services are all non-significant and do not improve the regression models. For 2020, the decrease of the variance explained by the disciplinary profile of the university to 13.1% suggests that a change is taking place regarding the determining factors for universities´ IR OA share.

Evidence from qualitative interviews with 20 OA administrators from German universities show that the designated use of IR has shifted in the past. Besides the collection of metadata that support the information needs of the universities’ management, university libraries have become active in the aggregation of content from other sources. Such activities could be a relevant factor in the explanation of the IR OA share. Aggregation thereby does not refer to articles behind paywalls only with the objective to make them OA—like in the case of DeepGreen—but also to content that is already OA. At best such usage of IR can be understood as a strategy of archiving that guarantees OA articles to remain OA or as an attempt to create legitimation for a repository that is rarely used by researchers. Further research is well advised to consider such collection and aggregation activities that university libraries undertake when aiming to explain differences in the IR OA share of universities.

Notes

https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv (accessed August 15, 2023).

https://www.medrxiv.org/ (accessed August 15, 2023).

https://www.biorxiv.org/ (accessed August 15, 2023).

The amalgamation of OA with research assessment also happens on the country-level. See as an example the UK research excellence framework as described in Ten Holter (2020).

This may happen via institutional repositories or current research information systems (CRIS).

The only mandate in the German university landscape that requires the archiving of full texts of publications on a repository was adopted by the University of Konstanz in 2015. The question whether or not the mandate violates the freedom of science guaranteed by the German constitution is subject of a lawsuit (Hartmann, 2017). However, the situation of non-university research institutions differs. For instance, the Helmholtz Association (https://www.helmholtz.de/en/, January 3, 2024) has adopted an OA policy in 2016 that requires OA to publications of their researchers (https://roarmap.eprints.org/158/, January 3, 2024).

https://open-access.network/en/services/oaatlas (accessed August 15, 2023).

https://www.projekt-deal.de/about-deal/ (accessed August 15, 2023).

Local infrastructures and services bring together a number of different components, including OA policies and mandates, and the existence of OA officers, websites with OA (rights) information and/or OA training activities. In the statistical model, the variables that are summarised in this hypothesis are tested individually. For the relevance of OA policies and mandates, see Picarra & Swan (2015); Lovett et al. (2017); and Herrmannova et al. (2019).

Such ‘avoidance of double work’-hypothesis is inspired by Xia (2008).

The hypothesis is inspired by evidence of disciplinary differences in the usage of IR OA (Spezi et al. 2012; Pinfield et al., 2014).

Analogous to the hypothesis for subject repository OA, ‘local infrastructures and services’ bring together a number of different components, including OA policies and mandates, and the existence of institutional repositories, OA officer, websites with OA (rights) information and/or OA training activities. In the statistical model, the variables that are summarised in this hypothesis are tested individually. Following Giesecke (2011, p. 531), a positive effect of the existence of institutional repositories on the IR OA share would support the ‘If you build it, they will come’-hypothesis. For the relevance of OA policies and mandates as possible determining factors of (institutional) OA shares, see Picarra & Swan (2015); Lovett et al. (2017); and Herrmannova et al. (2019)

The method for the matching of OA evidence is explicated in Hobert et al. (2021). The code is documented in https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3892951 (accessed August 15, 2023).

The data collection with detailed documentation has since been published for re-use (https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2965623, accessed August 15, 2023).

Source: GEPRIS database (DFG, https://gepris.dfg.de/gepris/OCTOPUS, accessed August 15, 2023).

Source: ROARmap (https://roarmap.eprints.org/,(accessed August 15, 2023).

Source: DEAL operations (https://deal-operations.de/aktuelles/publikationen-in-2020, accessed August 15, 2023).

The interviews were conducted in German. All quotations of the interviews are translations by the authors.

I-04, pos. 22; I-05, pos. 51; I-07, pos. 7, I-12, pos. 37, I-02, pos. 70-72, I-13, pos. 25; pos. 27, I-14, pos. 27, I-19, pos. 14.

I-07, pos.9.

I-01, pos. 53; I-08, pos. 42; I-19, pos. 60, pos. 66; I-20, pos. 33, pos. 117.

I-04, pos. 38, I-09, pos. 49; I-11, pos. 29, I-12, pos. 99, I-15, pos. 71, I-16. Pos. 43 I-17, pos. 51, I-20, pos. 33.

I-02, pos. 30, pos. 62; I-06, pos. 87; I-07, pos. 21; I-09: pos. 39; I-10, pos. 69; I-11, pos. 25; I-13, pos. 19; I-14, pos. 33; I-15, pos. 49; I-16, pos. 37; I-18, pos. 31; I-20, pos. 25; I-21, pos. 56.

I-07, pos. 19; I-13, pos. 25.

I-01, pos. 45; I-02; pos. 52; pos. 62; I-04, pos.32; I-05, pos. 45; I-06, pos. 93; I-10; pos. 69; I-11. 25; I-12, pos. 31; I-13, pos. 5; I-14, pos. 33; I-15, pos. 49; I-16, pos. 33; I-17; pos. 43; I-21, pos. 47.

https://info.oa-deepgreen.de/unterstuetzer/ (accessed August 15, 2023).

I-05, pos. 41; I-07, pos. 21; I-15, pos. 49; I-16, pos. 33; I-14, pos. 33.

I-01, pos. 53; I-05, pos. 55. See also Poynder (2016) and Tsay et al. (2017) for other examples.

I-05, pos. 39; I-06, pos. 93; I-11, pos. 25; I-15, pos. 49; I-14, pos. 33; I-16, pos. 33.

I-10, pos. 82.

In the German context most prominently (but not only) the contracts of project DEAL (mentioned in Interviews I-05, pos. 41, I-07, pos. 21; I-15, pos. 49; I-16, pos. 33; I-14, pos. 33).

I-01, pos. 45; I-02, pos. 54; I-05, pos. 45; I-07, pos. 19, pos. 23; I-11, pos. 27; I-13; pos. 19.

In the case of Wiley since July 1, 2019.

Information of the volume of third-party-funding were included in the data collection with dissatisfying results. For details, see the published data set of the study (Bruns et al., 2022).

References

Archambault, É., Amyot, D., Deschamps, P., Nicol, A., Provencher, F., Rebout, L., & Roberge, G. (2014). Proportion of open access papers published in peer-reviewed journals at the European and World Levels—1996–2013. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/scholcom/8

Arlitsch, K., & Grant, C. (2018). Why so many repositories? Examining the limitations and possibilities of the institutional repositories landscape. Journal of Library Administration, 58(3), 264–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2018.1436778

Björk, B.-C., Laakso, M., Welling, P., & Paetau, P. (2014). Anatomy of green open access. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(2), 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22963

Boltze, J., Höllerl, A., Kuberek, M., Lohrum, S., Pampel, H., Putnings, M., Retter, R., Rusch, B., Schäffler, H., & Söllner, K. (2022). DeepGreen: Eine Infrastruktur für die Open-Access-Transformation. o-bib. Das Offene Bibliotheksjournal Herausgeber VDB. https://doi.org/10.5282/o-bib/5764

Bosman, J., de Jonge, H., Kramer, B., & Sondervan, J. (2021). Advancing open access in the Netherlands after 2020: From quantity to quality. Insights. https://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.545

Bosman, J., & Kramer, B. (2018). Open access levels: A quantitative exploration using Web of Science and oaDOI data (e3520v1). PeerJ Inc. https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.3520v1

Bruns, A., Iravani, E., & Taubert, N. (2022). Open Access-related Infrastructures and Services at German Universities (OARIS). https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2965623

Collins, K. M. T., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Jiao, Q. G. (2006). Prevalence of mixed-methods sampling designs in social science research. Evaluation & Research in Education, 19(2), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.2167/eri421.0

Crow, R. (2002). The Case for Institutional Repositories: A SPARC Position Paper [ARL Bimonthly Report 223]. https://rc.library.uta.edu/uta-ir/bitstream/handle/10106/24350/Case%20for%20IRs_SPARC.pdf

Dalton, E. D., Tenopir, C., & Björk, B.-C. (2020). Attitudes of North American academics toward open access scholarly journals. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 20(1), 73–100. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2020.0005

Dempsey, L. (2014, October 27). Research information management systems: A new service category? LorcanDempsey.Net. https://www.lorcandempsey.net/research-information-management-systems-a-new-service-category/

Donner, P., Rimmert, C., & van Eck, N. J. (2020). Comparing institutional-level bibliometric research performance indicator values based on different affiliation disambiguation systems. Quantitative Science Studies, 1(1), 150–170. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00013

Fraser, N., Brierley, L., Dey, G., Polka, J. K., Pálfy, M., Nanni, F., & Coates, J. A. (2021). The evolving role of preprints in the dissemination of COVID-19 research and their impact on the science communication landscape. PLOS Biology, 19(4), e3000959. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000959

Freedman, D. A. (2009). Theory and practice. Cambridge core. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815867

Gargouri, Y., Lariviere, V., Gingras, Y., Brody, T., Carr, L., & Harnad, S. (2012). Testing the Finch Hypothesis on Green OA Mandate Ineffectiveness (arXiv:1210.8174). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1210.8174

Giesecke, J. (2011). Institutional repositories: Keys to success. Journal of Library Administration, 51(5–6), 529–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2011.589340

Ginsparg, P. (1994). First steps towards electronic research communication. Computers in Physics, 8(4), 390–396. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4823313

Ginsparg, P. (2011). ArXiv at 20. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/476145a

Hartmann, T. (2017). Zwang zum Open Access-Publizieren? Der rechtliche Präzedenzfall ist schon da! LIBREAS. Library Ideas, 32. https://libreas.eu/ausgabe32/hartmann/

Haucap, J., Moshgbar, N., & Schmal, W. B. (2021). The impact of the German ‘DEAL’ on competition in the academic publishing market. Managerial and Decision Economics, 42(8), 2027–2049. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.3493

Herrmannova, D., Pontika, N., & Knoth, P. (2019). Do authors deposit on time? Tracking open access policy compliance. ACM/IEEE Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL), 2019, 206–216. https://doi.org/10.1109/JCDL.2019.00037

Hobert, A., Jahn, N., Mayr, P., Schmidt, B., & Taubert, N. (2021). Open access uptake in Germany 2010–2018: Adoption in a diverse research landscape. Scientometrics, 126(12), 9751–9777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04002-0

Huang, C.-K., Neylon, C., Hosking, R., Montgomery, L., Wilson, K. S., Ozaygen, A., & Brookes-Kenworthy, C. (2020). Evaluating the impact of open access policies on research institutions. eLife, 9, e57067. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.57067

Jackson, A. (2002). From preprints to e-prints. The rise of electronic preprint servers in mathematica. Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 44(1), 23–32.

Kennison, R., Shreeves, S. L., & Harnad, S. (2013). Point & counterpoint the purpose of institutional repositories: Green OA or beyond? Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication. https://doi.org/10.7710/2162-3309.1105

Kindling, M., Kobialka, S., Martin, L., & Neufend, M. (2021). Bundesländer-Atlas Open Access/Atlas on Open Access in German Federal States. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5761153

Kirkman, N., & Haddow, G. (2020, June 15). Compliance with the first funder open access policy in Australia [Text]. University of Borås. http://informationr.net/ir/25-2/paper857.html

Kling, R., & McKim, G. (2000). Not just a matter of time: Field differences and the shaping of electronic media in supporting scientific communication. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 51(14), 1306–1320. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4571(2000)9999:9999%3c::AID-ASI1047%3e3.0.CO;2-T

Laakso, M., Matthias, L., & Jahn, N. (2021). Open is not forever: A study of vanished open access journals. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 72(9), 1099–1112. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24460

Larivière, V., & Sugimoto, C. R. (2018). Do authors comply when funders enforce open access to research? Nature, 562(7728), 483–486. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07101-w

Lovett, J. A., Rathemacher, A. J., Boukari, D., & Lang, C. (2017). Institutional repositories and academic social networks: Competition or complement? A study of open access policy compliance vs. research gate participation. Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication. https://doi.org/10.7710/2162-3309.2183

Lynch, C. A. (2003). Institutional Repositories: Essential Infrastructure For Scholarship In The Digital Age. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 3(2), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2003.0039

Lynch, C. A., & Lippincott, J. kl. (2005). Institutional repository deployment in the United States as of early 2005. D-Lib Magazine, 11(9). http://www.dlib.org/dlib/september05/lynch/09lynch.html?ref=lorcandempsey.net

Marshall, E. (1999). PNAS to join PubMed Central—On condition. Science, 286(5440), 655–656. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.286.5440.655a

Martín-Martín, A., Costas, R., van Leeuwen, T., & Delgado López-Cózar, E. (2018). Evidence of open access of scientific publications in Google Scholar: A large-scale analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 12(3), 819–841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2018.06.012

Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical background and procedures. In A. Bikner-Ahsbahs, C. Knipping, & N. Presmeg (Eds.), Approaches to qualitative research in mathematics education: Examples of methodology and methods (pp. 365–380). Springer.

Nicholas, D., Rowlands, I., Watkinson, A., Brown, D., & Jamali, H. R. (2012). Digital repositories ten years on: What do scientific researchers think of them and how do they use them? Learned, 25(3), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1087/20120306

Novak, J., & Day, A. (2018). The IR has two faces: positioning institutional repositories for success. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 24(2), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2018.1425887

Picarra, M., Swan, A., & contributor] McCutcheon, V. (2015, December). Monitoring Compliance with Open Access policies [Research Reports or Papers]. PASTEUR40A. http://www.pasteur4oa.eu/

Pinfield, S., Salter, J., Bath, P. A., Hubbard, B., Millington, P., Anders, J. H. S., & Hussain, A. (2014). Open-access repositories worldwide, 2005–2012: Past growth, current characteristics, and future possibilities. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(12), 2404–2421. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23131

Piwowar, H., Priem, J., Larivière, V., Alperin, J. P., Matthias, L., Norlander, B., Farley, A., West, J., & Haustein, S. (2018). The state of OA: A large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles. PeerJ, 6, e4375. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4375

Plutchak, T. S., & Moore, K. B. (2017). Dialectic: The aims of institutional repositories. The Serials Librarian, 72(1–4), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2017.1320868

Pölönen, J., Laakso, M., Guns, R., Kulczycki, E., & Sivertsen, G. (2020). Open access at the national level: A comprehensive analysis of publications by Finnish researchers. Quantitative Science Studies, 1(4), 1396–1428. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00084

Poynder, R. (2016, September 22). Open and Shut?: Q&A with CNI’s Clifford Lynch: Time to re-think the institutional repository? Open and Shut? https://poynder.blogspot.com/2016/09/q-with-cnis-clifford-lynch-time-to-re_22.html

Rentier, B., & Thirion, P. (2011, November 8). The Liège ORBi model: Mandatory policy without rights retention but linked to assessment processes. Berlin 9 Pre-conference on Open Access policy development Workshop. https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/102031

Rimmert, C., Schwechheimer, H., & Winterhager, M. (2017). Disambiguation of author addresses in bibliometric databases—Technical report. [Report]. https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2914944

Roberts, R. J. (2001). PubMed Central: The GenBank of the published literature. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(2), 381–382. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.98.2.381

Robinson-Garcia, N., Costas, R., & van Leeuwen, T. N. (2020). Open Access uptake by universities worldwide. PeerJ, 8, e9410. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9410

Severin, A., Egger, M., Eve, M. P., & Hürlimann, D. (2020). Discipline-specific open access publishing practices and barriers to change: An evidence-based review (7:1925). F1000Research. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.17328.2

Spezi, V., Fry, J., Creaser, C., Probets, S., & White, S. (2013). Researchers’ green open access practice: A cross-disciplinary analysis. Journal of Documentation, 69(3), 334–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-01-2012-0008

Suber, P. (2012). Open access. MIT.

Taubert, N. (2021). Green open access in astronomy and mathematics: The complementarity of routines among authors and readers. Minerva, 59(2), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-020-09424-3

Taubert, N., Hobert, A., Fraser, N., Jahn, N., & Iravani, E. (2019). Open Access—Towards a non-normative and systematic understanding (arXiv:1910.11568). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1910.11568

Taubert, N., Hobert, A., Jahn, N., Bruns, A., & Iravani, E. (2023). Understanding differences of the OA uptake within the German university landscape (2010–2020): Part 1—Journal-based OA. Scientometrics, 128(6), 3601–3625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04716-3

Ten Holter, C. (2020). The repository, the researcher, and the REF: “It’s just compliance, compliance, compliance.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(1), 102079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.102079

Tsay, M., Wu, T., & Tseng, L. (2017). Completeness and overlap in open access systems: Search engines, aggregate institutional repositories and physics-related open sources. PLoS ONE, 12(12), e0189751. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189751

van Westrienen, G., & Lynch, C. A. (2005). Academic Institutional Repositories Deployment Status in 13 Nations as of Mid 2005. D-Lib Magazine, 11(9). https://dlib.org/dlib/september05/westrienen/09westrienen.html

Vincent-Lamarre, P., Boivin, J., Gargouri, Y., Larivière, V., & Harnad, S. (2016). Estimating open access mandate effectiveness: The MELIBEA score. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(11), 2815–2828. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23601

Xia, J. (2008). A comparison of subject and institutional repositories in self-archiving practices. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 34(6), 489–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2008.09.016

Zervas, M., Kounoudes, A., Artemi, P., & Giannoulakis, S. (2019). Next generation institutional repositories: The case of the CUT institutional repository KTISIS. Procedia Computer Science, 146, 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2019.01.083

Zhu, Y. (2017). Who support open access publishing? Gender, discipline, seniority and other factors associated with academics’ OA practice. Scientometrics, 111(2), 557–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2316-z

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research within the funding stream “Quantitative research on the science sector”, project OAUNI (Grant Nos. 01PU17023A and 01PU17023B). Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Preprint versions: A preprint version of this paper has been archived on a subject repository (Taubert, N., Hobert, A., Jahn, N., Bruns, A., & Iravani, E. (2023). Understanding differences of the OA uptake within the Germany university landscape (2010–2020)—Part 2: Repository-provided OA (arXiv:2308.11965). arXiv. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2308.11965) as well as on the institutional repository (Taubert, N., Hobert, A., Jahn, N., Bruns, A., & Iravani, E. (2023). Understanding differences of the OA uptake within the Germany University landscape (2010–2020)—Part 2: Repository-provided OA. https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2982313).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taubert, N., Hobert, A., Jahn, N. et al. Understanding differences of the OA uptake within the German University landscape (2010–2020): Part 2—repository-provided OA. Scientometrics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-05003-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-05003-5