Abstract

Corporate social irresponsibility (CSI) refers to violations of the social contract between corporations and society. Existing literature documents its tendency to evoke negative consumer responses toward the firm involved, including unethical consumer behaviors. However, limited research attention deals with its potential impacts on prosocial consumer behavior. With six studies, the current research reveals that when consumers perceive harm due to CSI, they engage in more prosocial behavior due to the arousal of their anger. This effect is weaker among consumers who find the focal CSI issue more personally relevant but stronger among consumers with strong self-efficacy for promoting justice. Perceptions of CSI harm increase with the degree of control that the focal firm has over the CSI. This research thus establishes an effect of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behaviors, through the emotional mechanism of anger; it further shows that consumers seek to restore justice by engaging in prosocial behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

The rise in the importance of responsible marketing reflects today's consumer demands for transparency and socially responsible behavior from firms. This approach, focusing on the social, economic, and environmental impact of business practices, is key to building long-term customer trust and addressing societal grand challenges (de Ruyter et al., 2022). Emphasizing sustainability and inclusivity, responsible marketing is essential for businesses aiming to sustain a reputable and ethical market presence. However, in practice irresponsible corporate practices are not uncommon, and it can harm consumers, employees, the environment, or society in general. These practices might include violating social norms and rules (e.g., tax avoidance, bribery), violating human rights or employment conditions (e.g., child labor, long working hours), and polluting the environment (e.g., oil spill). All such practices constitute corporate social irresponsibility (CSI), which refers to a violation of the social contract between corporations and society (He et al., 2021; Russell et al., 2016) that undermines the welfare of community members (Donaldson, 1982). CSI tends to evoke negative consumer behaviors, such as complaints, negative word of mouth (NWOM), and reduced consumption (Valor et al., 2022); and even unethical consumer behaviors, such as punishing a firm by lying, stealing, cheating (Rotman et al., 2018; Schweitzer & Gibson, 2008), or verbally abusing employees (Komarova Loureiro et al., 2018).

Contrary to the widely studied negative and unethical consumer behaviors in the literature, in practice, prosocial consumer behaviors are often observed among consumers in response to CSI. For instance, following the BP’s infamous Deepwater Horizon oil spill, people actively joined clean-up efforts following the oil spill (Nash, 2010) even if those behaviors do not benefit them directly. Also, more than 15,000 individuals signed up through BP's official website and charitable organizations, environmental groups, and state agencies to aid in cleanup tasks along the coastlines of affected Gulf States (CBS, 2010). Notably, those volunteering for cleanup tasks were not necessarily from the Gulf community affected by the spill (Kwok et al., 2017). Furthermore, individuals have contributed donations to support the long-term well-being and resilience of the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem, as well as the individuals and communities that depend on it, through nonprofit organizations. For example, in 2011, the year immediately following the BP oil spill, Ocean Conservancy received a total revenue of $14.5 million, with a large part from individual donors (49%) (Ocean Conservancy, 2011). Such behaviors are representatives of prosocial consumer behavior that produce some benefit for others, even as it imposes costs or sacrifices on the person performing it (Penner et al., 2005; Small & Cryder, 2016; White et al., 2020). As in the BP oil spill, the beneficiary of prosocial behaviors ranging from: helping, volunteering, and donating to purchasing sustainable products (Cavanaugh et al., 2015; Small et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2022). It is not always possible to clearly identify the prosocial behaviors as it might be abstract or imagined groups of beneficiaries (e.g., wildlife) or society and the environment as a whole (Bastian & Crimston, 2016; Bazemore, 1998; Gray et al., 2014).

However, this phenomenon has not been explored in academic literature, resulting in limited insight into the mechanisms and conditions behind this counterintuitive effect. Consequently, there is a gap in understanding how firms and organizations can utilize this effect to enhance their responsible marketing strategies and practices. Theoretically, studying this phenomenon can enrich the literature on consumer behavior towards corporate misconduct by challenging traditional theories that focus on self-interest or negative responses and proposing the inclusion of altruistic and socially-driven reactions. It can potentially highlight the significance of moral emotions, particularly anger, not only for their known negative impact, but also as drivers of prosocial behavior in CSI scenarios. This opens a new area for exploration and links to the broader concept of restorative justice in business, where consumer prosocial actions are seen as means of seeking justice. In turn extending the theory's application beyond its conventional legal and social realms. Practically, this research can offer critical managerial strategies for socially responsible marketing in the wake of CSI. Firms and organizations can capitalize on consumer prosocial reactions, for instance, by using CSI incidents as opportunities to engage in social initiatives, thereby demonstrating a commitment to positive change. It also has implication in terms of how to create avenues for consumer participation in prosocial activities related to CSI, fostering collective positive action.

The current research focuses on investigating the prosocial role of anger that is related to compensating the harmed parties. If anger drives prosocial behaviors by third parties who observe moral wrongs, they likely advance the interests of the harmed parties (Van Doorn et al., 2014). This might include abstract groups of victims of moral violations (e.g., future generations, animals, society) (Bastian & Crimston, 2016; Bazemore, 1998; Okimoto et al., 2012). Specifically, because CSI represents a violation of the social contract, it renders general society and the environment as collective victims, and consumers who feel angry in response to CSI may feel motivated to restore justice by engaging in prosocial behaviors that redress and contribute to the well-being of society as a whole.

To clarify these effects, we consider an antecedent role of firm controllability, a key indicator of firm agency, which refers to whether the firm could have prevented the CSI event. In moral judgments, harm perceptions generally are based on the perceived agency of the wrongdoer and observers’ harm perceptions are stronger if the wrongdoer possesses greater moral agency (Gray et al., 2012a). If a firm that exhibits CSI possesses agency, consumers accordingly should perceive the CSI harm as more severe. Formally, we predict that firm controllability, as an indicator of moral agency, increases CSI harm perceptions and thereby arouses more anger.

We also consider some potential moderators in these links. Noting that extrinsic motivation can compensate for a lack of intrinsic motivation (Menges et al., 2017; Yeager et al., 2014), we anticipate that the relevance of the CSI issue to the consumer (Michaelidou & Dibb, 2008; Van den Bos, 2007), referring to the significance or meaningfulness of the issue to the individual consumer (Michaelidou & Dibb, 2008; Van den Bos, 2007), attenuates the effect of this consumer’s anger on their prosocial behavior. It can intrinsically motivate consumers towards prosocial actions to restore justice following a CSI event. In contrast, anger, as an extrinsic motivator, is triggered by external factors. The effect of anger in terms of inducing prosocial consumer behavior might be weaker among consumers who already sense strong issue self-relevance, reflecting the compensatory relationship between intrinsic motivation from self-relevance and extrinsic motivation from anger.

Another potential moderating effect involves consumers’ self-efficacy, or belief in their own ability, regarding whether they can contribute to and promote justice. Consumers with strong justice self-efficacy anticipate that their prosocial behaviors will be effective in restoring justice following CSI. We predict that the motivational power of their anger gets enabled and sustained by such positive self-beliefs, because they are confident that they can respond effectively to the anger-inducing event (Mikulincer, 1998) and attain desired outcomes (McKee et al., 2006; Wood & Bandura, 1989). Formally, we posit that the positive effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior increases among consumers with strong justice self-efficacy.

Across six studies, we thus examine how (mediating role of anger) and when (moderating effects of CSI issue self-relevance and justice self-efficacy) CSI harm induces prosocial consumer behaviors, while also considering the effect of firm controllability on perceived CSI harm. In turn, we make several contributions to extant literature. First, we advance CSI literature by broadening the consumer outcomes to include prosocial consumer behaviors, rather than just negative outcomes for consumers and the transgressing firm. Second, we extend literature on the prosocial role of anger by broadening the concept of victim compensation to include prosocial consumer behaviors that are not directed toward immediate, direct victims of the CSI. Third, we demonstrate the subjective nature of harm perceptions, such that the magnitude of perceived CSI harm is a function of moral agency, as can be informed by firm controllability over CSI. Fourth, for CSI literature, we identify two relevant moderators, involving CSI issue self-relevance as a form of intrinsic motivation and consumers’ perceptions of their own justice self-efficacy. As our findings specify, for consumers with low issue self-relevance and thus less intrinsic motivation to behave in a prosocial manner, anger can provide an extrinsic motivation to engage in prosocial behavior. These effects also are enhanced among consumers who feel capable of promoting justice and anticipate that their prosocial actions will help restore justice. Fifth, by investigating how a firm’s negative actions can motivate prosocial consumer behavior, through consumer emotions (anger), we extend previous research that focuses solely on the positive effects of firms’ own prosocial initiatives.

Furthermore, the research highlights the pivotal role of consumers in addressing the grand challenges posed by CSI that tackles environmental issues (e.g., anti-environmental practices), societal concerns (e.g., long working hours), and economic challenges (e.g., bribery). This study also contributes practical insights applicable to transgressing firms seeking to implement recovery strategies for CSI, as well as to other entities, including civic organizations, aiming to leverage CSI information for marketing endeavors aimed at fostering prosocial consumption or public prosocial behavior. The research offers specific guidance on identifying conditions for augmenting this effect that can be related to determining target segments for the effective implementation of such strategies. Moreover, the research's additional exploration in understanding the impact of CSI on prosocial behavior towards specific beneficiaries (e.g., customers of transgressing firms and victims of CSI) provides further practical insights in executing performing strategies.

Conceptual framework and hypotheses

CSI harm and anger

Moral violations committed by a group or society can engender negative emotional reactions, such as anger (Haidt, 2001, 2007; Tangney et al., 2007). According to the Theory of Dyadic Morality, judgments of moral violations result in subjective harm perceptions that generate negative emotions (Gray et al., 2012a, 2014; Schein & Gray, 2018). The suffering of a moral actor (i.e., harm to the victims) affects moral judgments of moral wrongs (Cushman, 2008; Gray & Schein, 2012; Spranca et al., 1991; Weiner, 1995) and can activate other-directed negative emotions such as anger, contempt, and disgust (Rozin et al., 1999). Among these negative emotions, anger has a notable prosocial role (van Doorn et al., 2014, 2018).

Anger typically emerges from the perception of harm, which threatens personal goals or interests, as noted by various researchers (Frijda, 1986; Lazarus, 1991; Roseman, 1991, 2018; Smith & Ellsworth, 1985). Beyond threats to oneself (Hutcherson & Gross, 2011), the awareness of harm to others can also trigger anger (Grappi et al., 2013). Anger extends beyond mere self-defense reactions (Graham et al., 2009; Hofmann et al., 2014; Schein & Gray, 2018). Even when consumers themselves are not directly affected by a corporate social irresponsibility (CSI) event, witnessing the suffering and injustice endured by others can provoke their anger (Antonetti & Maklan, 2016; Romani et al., 2013; Rotman et al., 2018). The perception of severe CSI leads consumers to feel and display heightened anger towards the company involved (Antonetti & Maklan, 2016). Such events are judged more critically, making it harder to justify the firm’s actions or maintain support for it (Matute et al., 2021). Actions perceived as more harmful are also deemed more blameworthy (Lange & Washburn, 2012; Malle et al., 2014), aligning with the moral judgment literature that indicates a direct correlation between perceived harm and the severity of moral judgments. Hence, it is predicted that perceptions of harm have a significant impact on moral judgments concerning CSI, with the potential to amplify condemnation and intensify consumer anger towards the culpable firm.

Anger and prosocial consumer behavior

Anger creates a sensed need to restore justice by penalizing the offender (Antonetti & Maklan, 2016) and motivates consumers to pressure firms to resolve issues (Antonetti et al., 2020; Romani et al., 2013). As noted, anger can produce negative consumer reactions that target the firm, such as reducing consumption and engaging in NWOM or complaining (Antonetti & Maklan, 2016; Grappi et al., 2013; Xie & Bagozzi, 2019; Xie et al., 2015). Moreover, anger can even induce consumers to behave unethically to punish firms that engage in CSI such as by verbally abusing employees and taking advantage of the firm (Komarova Loureiro et al., 2018), say negative things about the company to generate a negative public identity (Romani et al., 2013), and stealing (Schweitzer & Gibson, 2008).

However, the anger literature has also highlighted that it not only motivates individuals to punish the firm (e.g., Côté-Lussier, 2013; Hechler & Kessler, 2018; Laurent et al., 2016) but also encourages people to try to compensate the harmed parties (e.g., Gummerum et al., 2016; Lotz et al., 2011; Van Doorn et al., 2018). Surprisingly, as indicated by the references in Table 1 reveals, no research has yet taken an extended victim compensation perspective to examine how CSI harm and anger promote prosocial behaviors among consumers as potential collective victims of CSI.

Research has shown that when exposed to stories of poverty, people who experience anger are motivated by it (unlike those who feel guilt) to engage in prosocial behaviors, such as donating money (Montada & Schneider, 1989). Similarly, anger can promote general helping behaviors, support for community programs, prosocial political actions, and so on (van de Vyver & Abrams, 2015; Wakslak et al., 2007). These collected findings indicate the effectiveness of both punitive and prosocial reactions as means to restore unjust circumstances (Darley & Pittman, 2003; Lotz et al., 2011; Van Doorn et al., 2015). Although relatively rarely studied, victim compensation behaviors might be preferable to punishment, because compensation appears more effective for restoring justice, in that it moves victims away from disadvantageous positions and causes limited harm to others, whereas punishment degrades the perpetrator while doing little for the victim (Lotz et al., 2011; Van Doorn et al., 2018). In addition, third-party compensating behavior promises to benefit the actor, who can gain a better reputation through such actions, compared with if they were to punish perpetrators (Dhaliwal et al., 2021).

Most anger literature considers efforts to restore justice by compensating direct victims, but justice restoration concepts extend further, to include efforts to ensure justice for the wider community, such as by compensating victims of similar offenses (Wenzel et al., 2010). In this context, "victims" refer to anyone or anything perceived as vulnerable (Crimston et al., 2016; Singer, 1981). This might include specific groups such as children (Dijker, 2010), collective groups such as people in general (Cooley et al., 2017), or vague entities such as future generations, animals (Singer, 1975), or the environment (Bastian & Crimston, 2016). In the case of CSI, the corporate breach of the social contract defines society as the victim, so consumers who experience anger might be motivated to restore justice by engaging in prosocial actions that compensate and benefit all of society.

In previous literature, Romani et al. (2013) show that anger induces consumers to respond to CSI with constructive rather than destructive motives. Altruistic punishments might impose costs, but it also conveys benefits to others, such as in the example of boycotting a firm to pressure it to correct its wrongdoing. However, anger does not appear to induce punitive actions that signal destructive motives, such as trying to discredit the firm and its public reputation. We combine these insights to hypothesize:

H1

CSI harm has a positive effect on prosocial consumer behavior.

H2

Anger toward the firm mediates the positive relationship between CSI harm and prosocial consumer behavior.

Although our aim of the research is examining the role of anger in compensating the society or the environment, as demonstrated in Table 1, we seek to add more detail to considerations of general prosocial behavior by considering other possible outcomes. That is, we include consumer unethical behavior toward the firm and prosocial behavior toward immediate and direct victims, to replicate previous research on the impact of anger in extant literature (e.g., Lotz et al., 2011; Rotman et al., 2018). In addition, we include general unethical consumer behavior to understand the effect of anger and provide a more comprehensive test of the ethically relevant outcomes of CSI-induced anger and of the assertion that anger can motivate both positive and negative behaviors (Van Doorn et al., 2018).

Effect of firm controllability on CSI harm

The Theory of Dyadic Morality suggests that perceived harm is subjective and based on the moral agency of the wrongdoer (Carlson et al., 2022; Gray et al., 2012b; Schein & Gray, 2018). It is closely associated with inferences of moral responsibility (Feigenson & Park, 2006), because it depends on the agent’s ability to plan and exercise forethought (Hart & Honoré, 1985). When a moral agent commits a wrong, people assess its level of control, in an attempt to understand the causes of the harm. If the actions seem preventable, moral judgment tends to be negative and results in greater perceived harm; if they are less preventable, the judgment tends to be more lenient and result in lower perceived harm (Darley & Pittman, 2003; Monroe & Malle, 2017).

In a CSI context, firms are moral agents that can be held accountable and morally responsible for the harmful outcomes of their actions (Feigenson & Park, 2006; Rai & Diermeier, 2015). Moral judgments then reflect consumers’ causal inferences about firm controllability over the CSI event (Lange & Washburn, 2012; Vaidyanathan & Aggarwal, 2003; Voliotis et al., 2016), which may be determined by the level of negligence (Feigenson & Park, 2006; Weiner, 1985, 1995, 2006). When an CSI event is caused by negligence (even if not intentionally), firm controllability over the event is high, and due to the influence of this perception on consumers’ moral judgment of the firm, consumers likely perceive the CSI event as more harmful. For example, if an oil spill is due to the firm’s negligence (e.g., inadequate safety measures, poor maintenance of equipment, insufficient training, disregard for regulations), consumers morally judge the firm more harshly and perceive the harm as more severe. But if another oil spill were caused by external forces, such as severe weather, consumers likely judge the firm less severely and perceive weaker harms. Noting the predicted effects of harm perceptions on anger and prosocial consumer behaviors, we expect that firm controllability positively and indirectly influences consumer anger and prosocial behavior. Formally, we hypothesize:

H3

CSI harm mediates the effect of firm controllability on anger toward the firm.

Moderating role of CSI issue self-relevance

We define self-relevance as the significance or meaningfulness of an issue to an individual (Michaelidou & Dibb, 2008; Van den Bos, 2007), such that it can create an intrinsic motivation to address that issue. People are more inclined to exhibit intrinsic motivation for a particular activity, such as a job or task, if they perceive it as personally meaningful and relevant (Chalofsky & Krishna, 2009; Swiatczak, 2021; Thomas & Velthouse, 1990). Consumers characterized by stronger CSI issue self-relevance similarly should be intrinsically motivated to engage in prosocial behaviors, because they are more inherently interested in restoring the justice and compensating the harmed party of the focal CSI issue. Doing so would grant them greater meaning and self-defining significance. Consumers with weaker CSI issue self-relevance instead lack much intrinsic motivation because they perceive the prosocial behaviors to restore the disrupted justice relating to the focal CSI issue as less meaningful or less integral to their self-identity.

Furthermore, among consumers with stronger CSI issue self-relevance, we anticipate a weaker motivating influence of anger, due to the compensatory relationship between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. That is, in moral judgments of CSI, motivation instigated by anger is external; it originates from observers’ exposure to the external stimulus of the harmful event (Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009; Van Doorn et al., 2014). This external force motivates observers to achieve the instrumental goal of restoring justice by compensating victims, but this motivation does not entail personal enjoyment or lead to the achievement of self-relevant goals. Instead, anger extrinsically motivates consumers to restore justice that has been disrupted by the CSI event and provide restitution to the broader, collective victims of the CSI harm, through their prosocial behaviors.

Also, in line with the compensatory roles of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation (Menges et al., 2017; Yeager et al., 2014), intrinsically motivated people tend to exhibit greater behavioral persistence and less susceptibility to situational factors or transient personal states, including emotional fluctuations and experiences (Kuvaas et al., 2017). In contrast, for people with less intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivators and forces can play a compensatory role and motivate them to perform, such as in job settings, where family motivation has a compensatory effect and can energize workers and reduce stress (Menges et al., 2017). Similarly, evoking prosocial and self-transcendent purposes into learning processes can increase students’ diligence and persistence in tedious learning tasks that typically do not generate high intrinsic motivation (Yeager et al., 2014).

Applying these notions to our study setting, we predict that CSI-induced anger serves as an extrinsic motivator that has a stronger effect on prosocial behaviors among consumers with weaker issue self-relevance, who also have relatively little intrinsic motivation. Notably, anger’s prosocial role appears particularly salient when third-party observers do not identify themselves as directly connected to the focal issues (Gummerum et al., 2016; Van Doorn et al., 2018). However, for consumers with stronger CSI issue self-relevance, their already elevated intrinsic motivation makes anger less relevant (even if it still may have some influence) for encouraging their prosocial behaviors. We hypothesize:

H4

CSI issue self-relevance moderates the effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior, such that among consumers with stronger (weaker) CSI issue self-relevance, anger has a weaker (stronger) positive effect on prosocial consumer behavior.

Moderating role of consumers’ justice self-efficacy

We define justice self-efficacy as a belief in one's own ability to make the world more just or restore injustices as needed (Mohiyeddini & Montada, 1998). More generally, people’s pursuit of and commitment to a goal-oriented behavior depends on their self-efficacy and confidence that they can complete the relevant tasks and achieve their goals (Bandura, 1977; Bandura & Locke, 2003). Self-efficacy enhances their assessment, anticipation, and expectation of positive outcomes of goal-oriented behaviors (McKee et al., 2006; Wood & Bandura, 1989), which then motivates greater efforts and behavioral commitment (Bandura & Locke, 2003). We predict that it also might strengthen the positive effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior, because justice self-efficacy leads consumers who are angered by CSI harm to perceive their prosocial behaviors as more effective in achieving their goal of restoring justice disrupted by CSI. As a goal-oriented emotion (Tagar et al., 2011), anger can promote prosocial behaviors that in turn support the achievement of a justice restoration goal (e.g., Berkowitz & Harmon-Jones, 2004; Kuppens et al., 2003; Van Doorn et al., 2014). The significant motivational power of anger should be intensified by a positive self-perception, such as confidence in one’s own capacity to respond effectively to the anger-inducing event (Mikulincer, 1998). Therefore, consumers who experience anger in response to a CSI event and also possess strong justice self-efficacy likely are strongly motivated to engage in prosocial behaviors, due to their optimistic expectations of the effectiveness of their behaviors. However, if consumers’ justice self-efficacy is low, even if they experience anger in response to CSI, they are less inclined to participate in prosocial behaviors, because they are pessimistic about their ability to achieve the desired outcomes. Formally, we posit:

H5

Justice self-efficacy positively moderates the positive effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior, such that among consumers with stronger (weaker) justice self-efficacy, anger exerts a stronger (weaker) positive effect on prosocial consumer behavior.

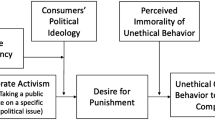

Fig. 1 presents the overall conceptual framework.

Conceptual framework. Note: The dotted line represents the hypotheses for the indirect effects. Specifically, H2 examines the mediating effect of anger towards the firm on the effect of CSI harm and prosocial consumer behavior. H3 investigates the mediating effect of CSI harm on the effect of firm controllability and anger towards the firm

Overview of studies

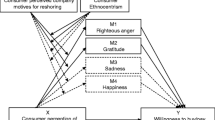

With this research, we examine the impact of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behavior, through the influence of anger, as well as how firm controllability influences these relationships. Furthermore, we investigate potential variability in the effects of anger due to the moderating effect of issue self-relevance and justice self-efficacy. To achieve these insights, we conducted six main studies. Four additional studies were also conducted to support main studies and placed in an appendix. Each study is briefly summarized in Table 2.

In Study 1, we examine whether CSI harm influences prosocial consumer behavior. In Study 2, we test for the mediating role of anger and the effect of firm controllability on CSI harm. Study 3 also pertains to the mediating role of anger; we control for other emotions (disgust, contempt) and test for the predicted moderating role of CSI issue self-relevance. In Study 4, we again test the mediating role of anger while controlling for other mediators, namely, guilt, disappointment, and perceived betrayal. Study 5 provides a test of the model, including the effect of firm controllability on CSI harm perceptions, the resulting influences on anger arousal and prosocial consumer behavior, and the moderating role of CSI issue self-relevance. Finally, Study 6 examines a moderating effect of justice self-efficacy as well as CSI issue self-relevance and replicates the mediating effect of anger with controlling for a mediating effect of moral self-presentation.

In terms of additional studies, Studies 1a and 1b replicates the effect of CSI harm on prosocial behavior in different experimental environments. In Studies 3a and 4a, similar to Studies 3 and 4, we validate the mediating effect of anger while controlling for other potential mediators (disgust, contempt, sympathy and moral identity). In Study 3a, we further test the moderating effect of CSI issue self-relevance and also consider other potential moderators (other-regarding value and negative reciprocity), to rule out these effects.

In addition, for each study, we conduct additional analyses to gain further insights. For example, by checking if justice restoration mediates the effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior, we also gain empirical evidence in support of our prediction that justice restoration goals drive people’s CSI-induced anger to engage in general prosocial consumer behavior (Studies 4 and 4a). We additionally examine a potential moderating effect of age on the effects of firm controllability and CSI harm (Studies 2 and 5).

With this research, we also note the effects of CSI harm perceptions and anger (and other potential mediators) on different consumer behaviors. That is, we include consumer unethical behavior toward the firm (Studies 1a, 4, 4a, and 5) and prosocial behavior toward immediate and direct victims (Study 4a), in an effort to replicate previous research on the impact of anger in extant literature (e.g., Lotz et al., 2011; Rotman et al., 2018). In addition, we include general unethical consumer behavior (Studies 1, 1b, 3, and 3a) to understand the effect of anger and provide a more comprehensive test of the ethically relevant outcomes of CSI-induced anger and of the assertion that anger can motivate both positive and negative behaviors (Van Doorn et al., 2018). Other possible forms of prosocial consumer behavior in CSI contexts include prosocial behavior toward the firm (Study 3) and the firm’s customers (Study 4a). We conduct additional analyses to test the potential mediating effect of anger between CSI harm and these behaviors (Studies 3, 3a, 4, and 4a).

Study 1: CSI harm and prosocial consumer behavior

In Study 1, we examine the effect of CSI harm on general prosocial consumer behavior. In H1, we predicted that CSI harm leads consumers to engage in prosocial consumer behavior in general. Also, we test if CSI harm induces general unethical consumer behavior, not necessarily toward the transgressing firm, that mirrors the effect on prosocial consumer behavior.

Procedure

A total of 157 Prolific participants were randomly assigned to a CSI condition or non-CSI condition. In the CSI condition, they received information about a food retailer that was selling expired food, leading to the risk of physical harm to consumers who consumed the products. In the non-CSI condition, participants instead read about the firm's conventional practice of releasing an annual report. Then, participants respond to a manipulation check about their perception of CSI harm (Graham et al., 2011) (α = 0.95).

Next, participants played 10 rounds of a card game that tracked whether they cheated for financial gain. We explained that participants could earn additional rewards, based on their achievements in the game. For every round, two cards appeared, and participants had to choose one card and check if a joker appeared. At the end of each round, a question asked, “Did you draw a joker?” Participants were to select the “Win” button if the chosen card was not a joker and “Lose” if it was. If they selected “Win,” participants received an additional financial reward (50 pounds), whereas if they selected “Lose,” they lost 50 pounds. Participants were unaware that the game was not random and rather was programmed to ensure they had 0 pounds remaining at the end of the 10 rounds if they were honest. Prior to joining the game, they had the option to dedicate extra time to complete additional survey to help other researchers; we clearly emphasised the voluntary, non-compensatory nature of this request. After the study, we debriefed participants once they had finished the game and paid them for taking part; the amount of payment was unaffected by the results of the game.

Results and Discussion

The t-test demonstrates that the harm manipulation was successful (Mnoharm = 3.05, MCSIharm = 6.01; t(137) = -18.76, p < 0.001). The chi-square test of independence revealed an association (χ2(1) = 9.41, p = 0.002), in support of H1, such that a larger proportion of participants in the high CSI harm condition engaged in prosocial behavior than did in the low CSI harm condition (observed frequencies: CSI = 75, no CSI = 69; expected frequencies: CSI = 70, no CSI = 75). Another chi-square test of independence, conducted to assess the influence of CSI harm on general unethical consumer behavior, instead revealed insignificant effects.

This empirical evidence supports the notion that CSI harm can elicit general prosocial consumer behavior. Stronger harm perceptions increased people’s likelihood of behaving prosocially but also their likelihood of behaving unethically in general. By asking their willingness to help other researchers without any extra compensation for their time before playing a game, we rule out a potential moral cleansing effect, such that people might be more likely to act prosocially after they have acted unethically (Kalanthroff et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021).Footnote 1 With Study 2, we move on to test the predicted mediating role of anger and the effect of firm controllability on perceived CSI harm that affects anger.

Study 2: Firm controllability, CSI harm, and anger

In addition to investigating the mediating role of anger toward the firm in the relationship between CSI harm and prosocial consumer behavior, with Study 2 we test for the effect of firm controllability on perceived CSI harm and how it influences anger. Because gender and age affect moral maturity levels and people’s moral judgments (McNair et al., 2019; Wark & Krebs, 1996), we control for their effects across analyses. We anticipate it also may have an influence on how firm controllability—a moral agency factor that relates to a deontological (rather than utilitarian) moral judgment disposition—affects CSI harm perceptions. That is, we predict a positive moderating effect of participants’ age on the relationship between firm controllability and CSI harm perceptions, in that older adults are more likely to consider the moral agency related to firm controllability to evaluate CSI harms.

Procedure

We randomly assigned 214 Prolific participants to one of three conditions: no CSI harm, high controllability CSI harm, and low controllability CSI harm. Similar to Study 1a, we presented information about a shipping company. In the no CSI harm condition, we simply offered general information about the company. In the high controllability CSI harm condition, an oil spill was caused by a mechanical breakdown by an old ship, which represents something the firm can control. The low controllability CSI harm condition instead described the oil spill as caused by both controllable and uncontrollable factors, namely, a mechanical breakdown due to the old age of the ship and severe weather. After reading the assigned description, participants indicated their perception of CSI harm, their feelings toward the firm, and their willingness to help others. Those assigned to the low and high controllability CSI harm conditions also indicated perceptions of firm controllability over the CSI.

To assess anger, we used a three-item scale (angry, mad, very annoyed; α = 0.95) (Xie et al., 2015). For CSI harm perceptions, we relied on another three-item scale (α = 0.95) (Graham et al., 2011). Helping behavior was evaluated using a four-item scale adapted from Yi and Gong (2013) (α = 0.95). Perceived firm controllability was measured by asking participants to rate the extent to which the company had control over the oil spill (Klein & Dawar, 2004).

Results and discussion

The t-test indicated that the harm manipulation was successful (Mno harm = 3.47, Mlow controllability = 4.61, t(141) = 6.52, p < 0.001; Mhigh controllability = 5.07, t(140) = 8.60, p < 0.001). The t-test also indicated that the controllability manipulation was successful (Mlow controllability = 5.15; Mhigh controllability = 6.65, t(136) = 8.64, p < 0.001). We employed PROCESS model 4 (Hayes, 2018) to test the mediating role of anger between CSI harm and prosocial consumer behavior. Although the direct effect of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behavior was insignificant, it revealed a significant index of the mediation of anger toward the firm (indirect effect: 39, SE: 0.17, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.06, 0.73]), and all relevant paths were significant (no harm vs. low + high controllability: CSI harm to anger: β = 2.16, p = 0.00; anger to prosocial consumer behavior: β = 0.18, p = 0.00). Thus, we can confirm H2.

With the limited sample of participants assigned to low and high controllability CSI harm conditions, we also tested the mediating role of CSI harm between firm controllability and anger toward the firm using PROCESS model 4 (Hayes, 2018). While the direct effect of firm controllability on anger towards the firm was insignificant, the index of mediation was significant (indirect effect: 28, SE: 0.11, 95% CI [0.06, 0.52]), as were the relevant paths (firm controllability to CSI harm: β = 0.46, p = 0.01; CSI harm to anger: β = 0.62, p = 0.00), in support of H3.

With this same sample of low and high controllability CSI harm conditions, we conducted a serial mediation analysis with PROCESS model 6 (Hayes, 2018) to explore if firm controllability, as a moral agency antecedent of CSI harm perceptions and consumer anger, further affected prosocial consumer behavior, as their outcome variable. Although the direct effect of firm controllability on prosocial consumer behavior was insignificant, a bootstrap analysis revealed a significant index of the mediation of harm and anger between firm controllability and prosocial consumer behavior (indirect effect: 0.06, SE: 0.04, 95% CI [0.00001, 0.15]). We also found significance for all paths (firm controllability to CSI harm: β = 0.45, p = 0.01; harm to anger: β = 0.61, p = 0.00; anger to helping: β = 0.23, p = 0.01). Moreover, we employed PROCESS model 7 (Hayes, 2018) to test for a moderating role of age between firm controllability and harm while controlling for the effect of gender; this effect was insignificant.

Thus, with Study 2, we establish that anger mediates between the harm caused by CSI and prosocial consumer behavior. We also confirm that firm controllability enhances perceptions of CSI harm, which intensify consumer anger. However, we do not find any moderating role of age. With a serial mediation model, we also examine if firm controllability, as a moral agency antecedent of CSI harm perceptions and consumer anger, further affects their key outcome, namely, prosocial consumer behavior.

In all the preceding studies, we have manipulated harm (though in different ways). Yet harm is perceived subjectively (Schein & Gray, 2018), which suggests the need to measure it. We also note the potential influences of other mediators, such that we need to test for the mediating role of anger while controlling for those effects. Nor have we addressed the predicted moderating role of issue self-relevance. Therefore, in Study 3, we investigate the mediating role of anger while controlling for other emotions and test the moderating effect of CSI issue self-relevance in a scenario in which we measure harm. Study 3 also captures various prosocial consumer behaviors, such as donating and purchasing environmentally friendly products.

Study 3: Mediating role of anger and moderating role of CSI issue self-relevance

In Study 3, we examine the mediating role of anger and control for potential mediating effects of contempt and disgust, which represent other-condemning emotions (Hutcherson & Gross, 2011) that are prevalent in reactions to observed moral transgression (e.g., CSI), along with anger (Xie et al., 2015). As in Study 2, we control for age and gender, but here, we also control for CSI types and product involvement. Rather than examining the impact of a single CSI, with Study 3, we evaluate effects across three types (tax avoidance, employee mistreatment, and product defect), to enhance the generalizability of the results. We do not expect the CSI types to influence the effect of harm on prosocial consumer behavior, because consumers tend to express anger toward the firm in response to all types of CSI (Xie & Bagozzi, 2019). We control for the effect of involvement with specifically identified products, which seemingly could influence consumers’ information processing and evaluations of the incident (Petty et al., 1983). Overall, we anticipate that anger mediates the impact of harm on prosocial consumer behavior, even after controlling for the other potential mediators (contempt and disgust) and the effects of CSI type and product involvement. Yet the effect of such anger should be weaker among people who feel closely related to the issue.

Similar to Study 1, we additionally examine the impact of anger on general unethical consumer behavior to address the inconsistent results and to obtain more robust evidence of the prosocial role of anger. We also added an assessment of the impact of anger on prosocial consumer behavior directed toward the firm, to establish the scope of prosocial consumer behavior that can be motivated by anger. We do not expect anger to enhance prosocial consumer behavior toward the firm, because such behavior would not enable consumers to achieve justice restoration.

Procedure

A total of 282 Prolific participants were randomly assigned to three CSI conditions (tax avoidance, employee mistreatment, product defect), committed by a coffee company. Participants completed items related to perceptions of CSI harm, self-relevance of the CSI, and their emotional reactions (anger, disgust, contempt). Then, they answered questions about their willingness to engage in general prosocial behavior, prosocial behavior toward the firm, and general unethical behavior. We also asked about their weekly coffee consumption, to gauge their level of product involvement, and their age and gender.

The CSI harm measure was adapted from Graham et al. (2011) (α = 0.94). We assessed anger with a three-item scale (angry, mad, very annoyed, α = 0.97) (Xie et al., 2015); the measures for disgust (α = 0.97) and contempt (α = 0.96) came from the same source (Xie et al., 2015). For prosocial consumer behavior, we used a five-item scale (α = 0.69) (Cavanaugh et al., 2015) that referred to various types of ethical behavior (e.g., donating, volunteering for a charity, buying products made from recycled materials). Measures of willingness to help firms captured prosocial consumer behavior toward the firm (α = 0.91), according to a four-item scale adapted from Johnson and Rapp (2010). We also adapted a five-item scale of customer dysfunctional behavior (α = 0.66) (Reynolds & Harris, 2009), such that respondents had to indicate how likely they would be to approve of certain actions. With this indirect measure of unethical consumer behavior, we reduced social desirability bias concerns. The self-relevance measures came from Zaichkowsky’s (1985) work, comprising three-item scales (relevant, related, associated; α = 0.85). The responses appeared on seven-point scales (see the Appendix for the full measures).

Results and Discussion

A mediation analysis, using bootstrapping (Model 4; Hayes, 2018), showed support for our theorizing. While the direct effect of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behavior is insignificant, the effect of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behavior was still significantly mediated by anger toward the firm when we controlled for the mediating effects of contempt and disgust (indirect effect: 0.15, SE: 0.07, 95% CI [0.003, 0.29]), and all paths were significant (CSI harm to anger: β = 0.85, p = 0.00; anger to general prosocial consumer behavior: β = 0.18, p = 0.03), in support of H2. However, the indexes for mediation by contempt and disgust were insignificant (Table 3). Moreover, according to mediation tests of anger, in which we included disgust and contempt, involving CSI harm and both prosocial consumer behavior toward the firm and general unethical consumer behavior, these indexes were insignificant.

While controlling for the mediating effects of contempt and disgust, we employed PROCESS model 14 (Hayes, 2018) and tested the full moderated mediation model, in which CSI harm is the independent variable, anger toward the firm is the mediator, prosocial consumer behavior is the dependent variable, and issue self-relevance is the moderator between the mediator and dependent variable. The paths from CSI harm to anger (β = 0.85, p = 0.00) and from anger to prosocial behavior (β = 0.17, p = 0.046) were significant; the moderating effect of self-relevance on the effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior was marginally significant (β = -0.10, p = 0.06). A more conservative test (two-tailed) revealed that the index of the moderated mediation effect was not significant (indirect effect: -0.09, SE: 0.05 95% CI [-0.18, 0.01]). A one-tailed test for mediation and moderated mediation effects might be relevant though, because the direction of such effects depends on the preconditional influences of the main effect of the independent variable on the mediator and mediator on the outcome variables. Therefore, we conducted a one-tailed moderated mediation test, which produced a significant index of moderated mediation (indirect effect: -0.09 SE: 0.05, 90% CI [-0.17, -0.0014]). The effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior was mitigated by the level of CSI issue self-relevance (weak, indirect effect: 0.27, SE: 0.11, 90% CI [0.09, 0.45]; strong, indirect effect: 0.01, SE: 0.09, 95% CI [-0.13, 0.17]). Therefore, we found partial support for H4 with a conservative two-tailed test and full support with a one-tailed test.

We confirm a significant effect of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behavior, validate the mediating role of anger toward the firm, and rule out alternative mechanisms, such as disgust and contempt. In addition, this study supports H4, in which we predicted that the prosocial role of anger (and CSI harm through anger) is mitigated by consumer CSI issue self-relevance. One limitation is that the mediating effect of anger appears barely significant (lower CI is 0.003) when we control for the effects of disgust and contempt. In showing that anger did not significantly mediate the impact of harm on general unethical consumer behavior, we also provide further evidence of the prosocial role of anger.Footnote 2 Finally, by revealing an insignificant impact of anger on prosocial consumer behavior toward the firm, our findings suggest that the links of prosocial consumer behavior, CSI harm, and anger do not extend to direct support for the firm.

Study 4: Mediating role of anger and effect of justice restoration motivation

For this test of the mediating role of anger, we compare it with and control for mediating effects of some potential emotional and cognitive mediators: guilt, disappointment, and perceived betrayal. Literature about the moral cleansing effect suggests that guilt can lead people to engage in prosocial behaviors (Kalanthroff et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021). Both perceived betrayal and disappointment can be caused by psychological contract violations (Montgomery et al., 2018). These elements may be particularly relevant in our research context, because CSI violates consumers’ expectations that a firm should be socially responsible and adhere to social norms. In addition to age and gender, in Study 4, we control for the location where CSI happened, in an attempt to explore potential location effects. On the basis of our previous findings, we anticipate that anger mediates the effect of CSI harm perceptions on prosocial consumer behavior, controlling for the effect of other factors (guilt, disappointment, perceived betrayal, CSI location, age, and gender). Furthermore, we test the mechanism of justice restoration between anger and prosocial consumer behavior and the mediating effect of anger on unethical consumer behavior toward the firm.

Procedure

232 Cloud Research participants, residing in the United States, received information about an appliance company that caused significant environmental harm by releasing hazardous substances into the environment. Two randomly assigned conditions indicated different locations for the CSI occurrence, namely, in the United States, where respondents live, or in Germany, which represents a geographically distant location but features corporate sustainability practices that are similar to those adopted by U.S. companies (KPMG, 2022). Following the description, participants rated their CSI harm perceptions, feelings toward the firm, justice restoration motivation, willingness to help other customers in general, and likelihood to behave unethically toward the firm.

The CSI harm measure featured a three-item scale (α = 0.82) (Graham et al., 2011). Anger was measured with a three-item scale (α = 0.95) (Xie et al., 2015). Justice restoration motivation was measured with a five-item scale (α = 0.92). Helping other customers was measured with a four-item scale (α = 0.92) (Yi & Gong, 2013). Perceived betrayal was measured with a three-item scale (cheated, betrayed, lied) (α = 0.92) (Grégoire & Fisher, 2008). Disappointment was measured with one item (White & Yu, 2005), as was guilt (Dahl et al., 2005). Unethical consumer behavior toward the firm was assessed with a three-item scale adapted from Rotman et al. (2018) (α = 0.90). All responses involved seven-point scales (see Appendix).

Results and Discussion

A mediation analysis using a bootstrapping approach (Model 4; Hayes, 2018) provided support for our theorizing: while the direct effect of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behavior was insignificant, the effect of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behavior was significantly mediated by anger toward the firm, even after controlling for mediating effects of perceived betrayal, disappointment, and guilt (CSI harm to anger: β = 0.67, p = 0.00; anger to prosocial consumer behavior: β = 0.25, p = 0.02; indirect effect: 0.16, SE: 0.08, 95% CI [0.001, 0.33]). We found insignificant indexes of mediation for perceived betrayal, disappointment, and guilt (Table 4). The direct effect of CSI harm on unethical consumer behavior toward the firm was insignificant. The mediating effect of anger on unethical consumer behavior toward the firm was also insignificant while controlling the effects of perceived betrayal, disappointment, and guilt. Instead, the mediating effect of disappointment between CSI harm and unethical consumer behavior toward the firm was significant (indirect effect: -0.12, SE: 0.05, 95% CI [-0.24, -0.04]). The paths for the mediating effect of guilt between CSI harm and unethical consumer behavior toward the firm was also significant, but the index of the mediation was insignificant.

In a serial mediation analysis, using bootstrapping (Model 6; Hayes, 2018), we determined that the direct effect of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behavior was insignificant, but the effect of harm on prosocial consumer behavior was serially mediated by anger toward the firm and justice restoration motivation (indirect effect: 0.10, SE: 0.04, 95% CI [0.03, 0.20]). All paths were significant (CSI harm to anger: β = 0.67, p = 0.00; anger to justice restoration motivation: β = 0.29, p = 0.00; justice restoration motivation to prosocial consumer behavior: β = 0.51, p = 0.00).

Thus, the mediating effect of anger remains significant even when we control for perceived betrayal, guilt, and disappointment, though barely so (lower CI is 0.001). This result seems reasonable, in that the added mediators are significantly correlated with anger. Study 4 confirms that angry consumers are more likely to engage in general prosocial behavior, motivated by their desire to restore justice.Footnote 3 Although we cannot confirm a mediating role of anger on unethical consumer behavior toward the firm when we control for the other mediators, the mediating effect of disappointment emerges as significant.

Study 5: Effect of firm controllability on CSI harm and moderating role of CSI issue self-relevance

In Study 5, we examined (1) the impact of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behavior; (2) the mediating role of anger toward the firm in the relationship between CSI harm and prosocial consumer behavior; (3) the influence of firm controllability on CSI harm perception, which can trigger anger toward the firm; and (4) the moderating effect of CSI issue self-relevance on the relationship between anger toward the firm and prosocial consumer behavior. The analysis controlled for age and gender. With extra analyses, we also tested the moderating effect of CSI issue self-relevance on the effect of anger on unethical consumer behavior toward the firm and the moderating effect of age on the relationship between firm controllability and CSI harm perception, as in Study 2.

Procedure

A total of 294 Prolific participants were randomly assigned to two CSI conditions (high and low controllability), both of which included information about an oil spill by a shipping company. In the high controllability condition, the description highlighted inadequate maintenance, outdated equipment, and negligent management—practices recommended by a recent health and safety audit prior to the incident—as the causes of the oil spill. In the low controllability condition, the oil spill resulted from both uncontrollable and controllable factors, including severe weather and an inadequate emergency response program for dealing with damage to flora and fauna. The order in which we presented the uncontrollable and controllable factors was random, to avoid sequence effects.

Participants answered questions about firm controllability over the CSI, perceptions of CSI harm, and emotional reactions (anger). They indicated their willingness to engage in prosocial behavior and demographic information (age and gender). Firm controllability was measured with one item (Klein & Dawar, 2004); CSI harm was measured with a three-item scale (α = 0.78) (Graham et al., 2011); anger was measured with a three-item scale (α = 0.92) (Xie et al., 2015); prosocial consumer behavior was captured with five items pertaining to prosocial consumption (α = 0.79) (Cavanaugh et al., 2015); unethical consumer behavior toward the firm featured a three-item scale adapted from Rotman et al. (2018) (α = 0.87); and the degree of issue self-relevance was assessed with a three-item scale adapted from Zaichkowsky (1985) (α = 0.89). All responses were measured on seven-point scales (see the Appendix).

Results and Discussion

The t-test demonstrated that the controllability manipulation was successful (Mlow controllability = 4.90, Mhigh controllability = 6.18; t(302) = -9.02, p < 0.001). While controlling for age, gender, and firm controllability, we tested the mediating role of anger between CSI harm and prosocial consumer behavior, using PROCESS model 4 (Hayes, 2018). The direct effect of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behavior was significant. Also, the index of mediation for anger was significant (indirect effect: 20, SE: 0.04, 95% CI [0.13, 0.27]), as were all relevant paths (CSI harm to anger: β = 0.63, p = 0.01; anger to prosocial consumer behavior: β = 0.32, p = 0.00), in support of H2. Moreover, we tested the mediating role of CSI harm between firm controllability and anger and revealed a significant direct effect of firm controllability on anger towards the firm. We also found a significant index of mediation of CSI harm (indirect effect: 25, SE: 0.09, 95% CI [0.08, 0.44]) and significant paths (firm controllability to CSI harm: β = 40, p = 0.003; CSI harm to anger: β = 0.63, p = 0.00), as predicted by H3.

With PROCSS model 14 (Hayes, 2018), we tested the moderating effect of issue self-relevance between anger and prosocial consumer behavior, controlling for firm controllability, age, and gender. The paths of CSI harm to anger (β = 0.63, p = 0.00) and anger to prosocial consumer behavior (β = 0.25, p = 0.00), as well as the moderating effect of issue self-relevance on prosocial consumer behavior (β = -0.05, p = 0.04), all were significant, as was the index of moderated mediation (indirect effect: -0.03 SE: 0.02 95% CI [-0.06, -0.003]). Thus, we can confirm H4. The effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior became mitigated among consumers who sensed the CSI as strongly relevant (weak, indirect effect: 0.21, SE: 0.04, 95% CI [0.13, 0.30]; strong, indirect effect: 0.10, SE: 0.14, 95% CI [0.03, 0.18]). When we also tested the moderating effect of issue self-relevance between anger and unethical consumer behavior toward the firm, the result was insignificant.

Also, with PROCSS model 7 (Hayes, 2018), we tested the moderating role of age across the links of firm controllability, harm, and anger, while controlling for effect of gender. In this analysis, firm controllability is the independent variable, CSI harm is the mediator, anger is the dependent variable, and age is a moderator between the independent variable and mediator. The paths of CSI harm to anger (β = 0.40, p = 0.00) and CSI harm to anger (β = 0.62, p = 0.00) were significant; the path for mediated moderation was only marginally significant (firm controllability × age: β = 0.02, p = 0.06). For the index of moderated mediation, we found significance at the 90% CI (indirect effect: 0.01 SE: 0.01, [0.001, 0.02]) but insignificance at the 95% CI (indirect effect: 0.01 SE: 0.01, [-0.0002, 0.02]). The effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior appeared mitigated if consumers are older (younger adults, indirect effect: 0.08, SE: 0.12, 90% CI [-0.16, 0.32]; older adults, indirect effect: 0.42, SE: 0.14, 95% CI [0.17, 0.70]).

A serial mediation analysis, using PROCESS model 87 (Hayes, 2018), provided insights into the effect of firm controllability, as a moral agency antecedent of CSI harm perceptions and anger, on prosocial consumer behavior. We also tested for the potential moderating effect of issue self-relevance. Thus, firm controllability provided the independent variable, CSI harm perception was the first mediator, anger toward the focal firm was the second mediator, issue self-relevance was the moderator, and prosocial consumer behavior was the dependent variable. All the paths were significant (firm controllability to CSI harm: β = 0.40, p = 0.004; CSI harm to anger toward the firm: β = 0.63, p = 0.00; anger toward the firm to prosocial consumer behavior: β = 0.25, p = 0.00; anger toward the firm × issue-self relevance: β = -0.05, p = 0.04), as was the index of moderated mediation (indirect effect: -0.01, SE: 0.01, 95% CI [-0.03, -0.001]). The effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior disappeared if consumers felt strongly related to the CSI (weak, indirect effect: 0.08, SE: 0.03, 95% CI [0.03, 0.16]; strong, indirect effect: 0.04, SE: 0.02, 95% CI [0.006, 0.09]), in further support for the hypothesized process.

Study 5 thus has successfully validated that CSI harm enhances prosocial consumer behavior, through anger toward the firm. Firm controllability also increases CSI harm perceptions, which elicit stronger anger. Yet the effect of anger on general prosocial consumer behavior decreases if consumers already perceive greater issue self-relevance. In the serial moderated mediation model, the impact of firm controllability, on both CSI harm perception and anger toward the firm, subsequently influences prosocial consumer behavior too. Age moderates this effect of firm controllability on CSI though, indicating that older adults tend to perceive CSI as more harmful if firm controllability is high; the statistical significance of this effect is only marginal though.

Finally, with Study 6, we test the moderating effect of justice self-efficacy, which we anticipate will enhance the effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior, but we also consider whether it might decrease the effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior.

Study 6: Moderating role of CSI issue self-relevance and justice self-efficacy

In addition to testing the moderating effect of justice self-efficacy and replicating the moderating role of CSI issue self-relevance on the relationship between anger toward the firm and prosocial consumer behavior, in Study 6 we control for another potential mediator, namely, moral self-presentation. A self-presentation is the intentional projection of a particular image to others, usually through conformity with socially appropriate verbal and nonverbal behaviors in specific circumstances (Baumeister, 1982; Hewitt et al., 2003; Snyder, 1974). Different self-presentation facets can result from morally relevant goals to project goodness (Banerjee et al., 2020). If exposure to CSI harms activate consumers’ moral mindset, rendering them more sensitive to others’ opinions and approval, it might motivate consumers to engage in more prosocial behaviors. Therefore, we measure a moral self-presentation variable, which can represent a moral mindset that guides a person’s behaviors. By testing its effect, along with the effect of anger, we can rule out the possibility that the effect of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behaviors is driven by a moral mindset, as might be activated by CSI harm.

Procedure

The 151 Prolific participants read about a food retailer that failed to manage its food waste adequately, such that it allowed the release of persistent, unpleasant odors and created risks to local plants and animals, which meant detrimental outcomes for both the local community and the environment. Participants indicated their perception of CSI harm and feelings toward the firm (i.e., anger); responded to questions related to their moral self-presentation tendency; indicated their willingness to engage in prosocial behavior; and provided demographic information (age and gender). We included the measures of CSI issue self-relevance and justice self-efficacy before providing the information about the company.

For CSI harm, we used a three-item measure (α = 0.79) (Graham et al., 2011). Anger was assessed with a three-item scale (α = 0.91) (Xie et al., 2015). Moral self-presentation was measured with a seven-item scale adapted from Lennox and Wolfe (1984) (α = 0.72). Prosocial consumer behavior was measured with a five-item scale (α = 0.65) (Cavanaugh et al., 2015). For the degree of issue self-relevance, we used a three-item scale adapted from Zaichkowsky (1985) (α = 0.87). For justice self-efficacy, we used three items (α = 0.87) adapted from Mohiyeddini and Montada (1998) and Jugert et al. (2016). All responses appeared on seven-point scales (see the Appendix).

Results and discussion

Using PROCESS model 4 (Hayes, 2018), and controlling for a mediating effect of moral self-presentation, the direct effect of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behavior was insignificant, but we still found a significant index of mediation by anger (indirect effect: 0.13, SE: 0.05, 95% CI [0.05, 0.24]; CSI harm to anger: β = 0.66, p = 0.00; anger to prosocial consumer behavior: β = 0.20, p = 0.00), validating H2. The indexes for mediation by moral self-presentation were not significant (see Table 5).

With PROCSS model 14 (Hayes, 2018), we tested the moderating effect of issue self-relevance between anger and prosocial consumer behavior, controlling for age and gender. The paths from CSI harm to anger (β = 0.66, p = 0.00) and from anger to prosocial consumer behavior (β = . 18, p = 0.01) and the moderating effect of issue-self relevance on prosocial consumer (β = -0.08, p = 0.02) all were significant, as was the index of moderated mediation (indirect effect: -0.06 SE: 0.03 95% CI [-0.11, -0.001]), in support of H4. The effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior became mitigated when consumers found the CSI strongly relevant to themselves (weak, indirect effect: 0.22, SE: 0.07, 95% CI [0.08, 0.36]; strong, indirect effect: 0.02, SE: 0.06, 95% CI [-0.11, 0.14]). In another application of PROCSS model 14 (Hayes, 2018), we tested the moderating role of justice self-efficacy between anger and prosocial consumer behavior. The paths from CSI harm to anger (β = 0.66, p = 0.00) and from anger to prosocial consumer behavior (β = 0.21, p = 0.002), the moderating effect of justice self-efficacy on prosocial consumer (β = 0.12, p = 0.02), and the index of moderated mediation (indirect effect: 0.08 SE: 0.04 95% CI [0.01, 0.17]) were all significant, and we thus confirm H5. The effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior increased when consumers perceived their own greater efficacy to promote justice (strong, indirect effect: 0.22, SE: 0.07, 95% CI [0.10, 0.36]; weak, indirect effect: 0.03, SE: 0.07, 95% CI [-0.09, 0.17]).

Thus, Study 6 successfully confirms the significant mediating effect of anger while controlling for the potential mediating effect of moral self-presentation. Furthermore, we replicate the effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior, noting its weaker effect for issues with strong self-relevance. Finally, we show that the effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior is greater if consumers sense their own justice self-efficacy.

General discussion

Theoretical implications

Across six studies, we show that CSI harm has a positive impact on prosocial consumer behavior. Specifically, CSI harm increases prosocial consumer behavior in general (Study 1), due to the arousal of anger toward the firm (Studies 2–6). Furthermore, when a firm has control over the CSI, consumers perceive the harm as more severe, resulting in increased anger toward the firm (Studies 2 and 5). Angry consumers are less likely to engage in prosocial behavior when they perceive the CSI issue as less relevant to themselves (Studies 3, 5, and 6) but more likely to do so when they have stronger justice self-efficacy beliefs (Study 6). These findings thus contribute to literature on CSI, anger, and prosocial consumer behavior, as specified in the next sections.

CSI

This research contributes to CSI literature in several ways. Extant research predominantly deals with negative consumer responses to transgressing firms, without noting potential impacts on positive outcomes, including prosocial consumer behaviors. By examining how anger can motivate people to seek to restore disrupted moral values, not just by punishing the offender but also by compensating the victims, the initial empirical evidence established herein clarifies that consumer responses to CSI are not limited to the focal CSI firm but also include general prosocial consumer behaviors. We also offer the empirical evidence that a primary driver of anger’s prosocial functions is its impact on people’s desire to restore justice (Study 4).

In researching how anger influences the effect of CSI on prosocial consumer behaviors, we controlled for other potential explanations and thereby establish the unique function of anger. That is, the significant prosocial role of anger persists even when we control for other condemning emotions (e.g., contempt, disgust) and various other emotional (e.g., sympathy, guilt, disappointment) and cognitive (e.g., perceived betrayal, moral identity, moral self-presentation) mechanisms that arguably might explain the influence of CSI harm on prosocial consumer behavior. The robustness of the prosocial function of anger in consumer responses to CSI is consistent with previous studies that indicate anger is a more effective driver of prosocial behavior than emotions like sympathy and guilt (Montada & Schneider, 1989), but it challenges some findings related to employees' compensatory behavior. Hericher and Bridoux (2022) indicate that sympathy significantly evokes employees’ prosocial behavior, whereas anger does not appear to be a significant mediator. We posit that perhaps employees feel somewhat responsible for their employer's actions, such that they do not take a third-party perspective; the prosocial function of anger primarily relies on the capacity of third parties to observe harms inflicted by moral wrongs. These distinct perspectives might explain the weaker effect of anger on prosocial behavior by employees.

To enhance the external validity of the research findings, we also examined the effects of harm using different measures (e.g., victim size), while controlling for other factors that may influence harm, including CSI types, locations of CSI, demographics, and frequency of product use. Various harm perceptions influence the impacts on anger and thus on prosocial behavior. Similarly, we use different measures of prosocial consumer behavior, such as helping others and donating time or money to a charity. Across six studies, we find consistent support for positive effects of CSI harm on different prosocial consumer behaviors. These findings thus broaden our understanding of how CSI harm can affect not only consumer behavior toward the transgressing firm but also prosocial consumer behavior in general, which provides important insights to other firms, along with the transgressing firm.

Finally, we acknowledge that perceptions of the magnitude of harm are subjective and based on the moral agency of CSI harm. Therefore, we specifically predict an impact of firm controllability on perceptions of CSI harm and thus anger. In support of this hypothesis, consumers perceive CSI caused by factors that are more controllable by the firm as more harmful than those caused by less controllable factors (Studies 2 and 5). This finding contributes to CSI literature by affirming that CSI harm is subjective and a function of the moral agency of the firm. If the firm’s moral agency and controllability is higher, as when a CSI event is due to a firm’s negligence or recklessness, the event is perceived as more harmful, all else being equal. This finding is consistent with a key tenant of Theory of Dyadic Morality, offered to explain third parties’ moral judgments of moral wrongs and highlight how moral agency, causation, and victims influence harm perceptions (Schein & Gray, 2018). As previous research shows, harm caused by accidents (less agency) is perceived as less severe than harms caused by intention, negligence, or recklessness (Carlson et al., 2022; Gray et al., 2022; Monroe & Malle, 2017).

Anger

This research demonstrates a prosocial role of anger in CSI contexts; such topics rarely have been researched previously. Some CSI research explores the effect of anger on boycotting, which might be considered a prosocial behavior, if it aims to benefit others or society. However, it also is punitive (Romani et al., 2013). To the best of our knowledge, this article offers the first validation of a direct positive effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavioral responses to CSI. This research also contributes to anger literature by examining its role in motivating prosocial behavior in general, not just targeted at direct victims. In prior anger literature (Van Doorn et al., 2014), a possible motive for consumers to engage in prosocial behavior is their desire to balance out disrupted moral values, as they relate to direct victims. Across six studies, we find that CSI-induced anger motivates consumers to engage in multiple prosocial behaviors, not only those to aid direct victims (Study 4a) but also in a general sense. This important finding has social implications; it indicates that victim compensation can be extended to include efforts to compensate and benefit various groups, not just immediate victims, including abstract and collective entities, such as society or the environment. In additional tests of the mediating effect of anger between CSI harm and prosocial consumer behavior toward the firm (Study 3) and toward other customers of the firm (Study 4a), we determine that the main difference between these behaviors is the target beneficiary. The effect on efforts to help the firm (i.e., offender) is not significant; the effect on helping other customers is. It appears that helping customers of the firm (but not the firm itself) resembles a form of prosocial consumer behavior that aims to restore justice.

Combining CSI and Anger

This research reveals a boundary condition of prosocial consumer behavior: For average consumers, a justice restoration goal leads them to seek to restore moral values disrupted by CSI harm, by behaving ethically and prosocially in general. Across four studies (Studies 3, 5, and 6), we show that this effect of anger largely disappears among consumers with a strong sense of self-relevance, because they already have a powerful intrinsic motivation to compensate the collective victims of CSI harm. In other words, issue self-relevance attenuates the extrinsic motivating role of anger for inducing prosocial consumer behaviors to restore justice by compensating victims. When issue self-relevance is lower, CSI-induced anger can compensate for a lack of intrinsic motivation and exert strong effects on consumers’ motivation to restore justice, which leads them to engage in prosocial behaviors. This finding that the prosocial motivation of anger can vary depending on factors that intrinsically motivate prosocial consumer behaviors complements prior arguments that anger’s prosocial function weakens when the need for justice restoration is lessened, such as when justice has been restored by other means (Van Doorn et al., 2014). That is, we find that the power of anger’s prosocial motivation diminishes when there are other sources of prosocial motivation.

Furthermore, we note that the effect of anger on prosocial consumer behavior is enhanced among people with heightened self-efficacy for promoting justice, such that they endeavor to restore justice and contribute to making the world more just. This moderating effect occurs because justice self-efficacy enhances beliefs that their prosocial actions effectively will restore disrupted justice. As our research suggests, the potency of anger’s prosocial motivation increases when prosocial actions seem efficacious for achieving the goal of justice restoration.

Prosocial Consumer Behavior

Finally, we contribute to literature on prosocial consumer behavior. A prior review indicates that prosocial consumer behaviors are driven by factors stipulated in the SHIFT framework (social influence, habit formation, individual self, feelings and cognition, and tangibility) (White et al., 2019). Yet limited research has examined how brands and firms might influence prosocial consumer behavior unintentionally. In another review, Small and Cryder (2016) find that firms’ positive, proactive initiatives, such as partnering with charitable organization (e.g., cause-related marketing), can promote prosocial consumer behavior; they call for more research on this topic. In response, we investigate how a firm’s negative actions, such as CSI, also can motivate prosocial consumer behavior, through consumer emotions (i.e., anger). This novel effect, which we explain on the basis of the role of emotions in prosocial consumer behavior, is consistent with a key factor in the SHIFT framework (White et al., 2019). By adding to previous research that primarily focuses on positive or self-directed moral emotions (e.g., gratitude, guilt) (Antonetti & Maklan, 2014; Bock et al., 2018; White et al., 2020), we establish a prosocial role of other-directed negative emotions (e.g., anger), particularly in relation to motivations to restore justice, when consumers encounter negative firm actions. Previous research also has identified a significant role of justice restoration in promoting prosocial consumer behavior (White et al., 2012), but our research is the first to integrate anger and justice restoration motivation to explain prosocial consumer behaviors, as are motivated by a firm’s negative actions.

Managerial implications

Even as we acknowledge potential positive effects resulting from CSI harm, we clearly do not endorse or recommend that any companies try to engage in CSI. All forms of CSI must be condemned and avoided, due to its detrimental societal and environmental consequences. As a key implication for managers though, we show that in the wake of CSI, firms should take a proactive approach to remedy and repair the harm inflicted, using initiatives that harness and activate consumers' prosocial motivation to restore justice.